When will the Federal Reserve raise interest rates?

Stay up to date:

United States

As the Federal Open Market’s Committee (FOMC) prepares to announce its latest decision on interest rates, the current state of the US economy, and particularly the health of the job market, will be paramount in their thinking.

Over the past few years, the United States has been a stand-out performer against other advanced economies.

With the country’s unemployment rate at 5.3% in June, close to what economists think of as the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment – the level at which further falls could be expected to push up consumer prices), and economists expecting the economy to grow at an annualized rate of 2.7% in the second quarter of 2015, there is growing consensus that the Fed will raise rates this year.

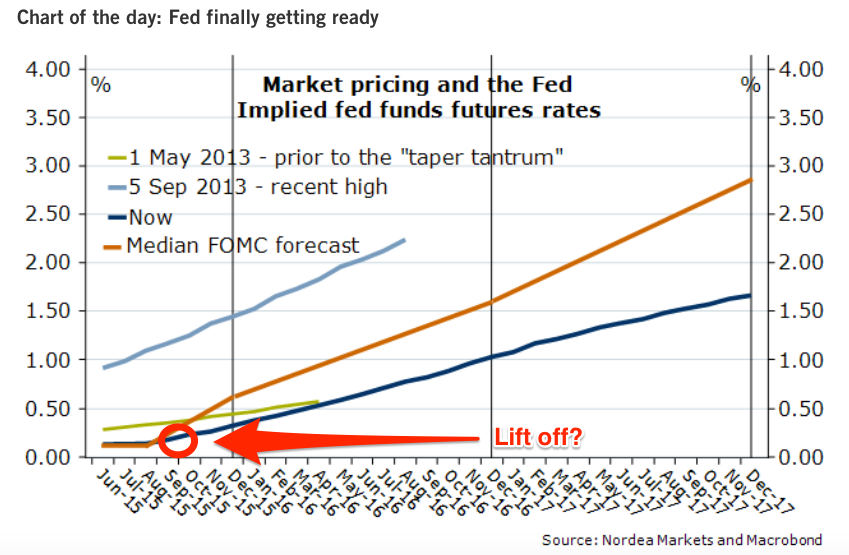

As this chart from Nordea shows, at present markets are pricing in the first rate hike in September:

Fed Chair Janet Yellen also gave a strong signal that the first rate move of her tenure is finally approaching, in a speech on 10 July:

Based on my outlook, I expect that it will be appropriate at some point later this year to take the first step to raise the federal funds rate and thus begin normalizing monetary policy.

However, there is still significant room for uncertainty over the exact timing of what will be the first rate move since December 2008. This is in large part because a number of FOMC members, including Yellen, have said that the headline measure of unemployment may be disguising the amount of remaining slack in the labour market.

Raising rates before allowing more of this slack to close by waiting until those who want to work find employment could keep a greater number of people out of the job market, which would not only hurt their finances but also reduce the potential output of the US economy as a whole.

Below are the various economic measures the Fed is looking at to make its decision.

The participation rate

The labour-force participation rate is the proportion of the total population aged 15 and older that is economically active (that is deemed to be either in employment or actively seeking employment). In the US the participation rate fell sharply in the aftermath of the financial crisis, from around 66% in January 2008 to 62.6% as at June 2015.

A substantial proportion of this fall can be attributed to long-term factors such as the ageing of the US population and increases in the numbers of young people in higher education. The combination of these has meant that retirees and students are growing as a share of the total US population, leading to a fall in the share of people counted as economically active (indeed the participation rate has been declining since the early 2000s).

Yet at least some of the decline in the participation rate could reflect people who have become discouraged from seeking work because of the relatively poor state of the job market, so don’t show up in the headline unemployment-rate statistics. As the economy continues to pick up, this category of non-active workers might see more opportunities present themselves and be tempted back into the workforce.

If this last group is large enough and can be lured back into employment, the US could continue to add jobs at a relatively brisk pace without having to worry too much about driving up consumer prices. In other words, it could mean that the FOMC has more time to play with than the headline figures suggest.

Unfortunately, as Nick Bunker points out over at Equitable Growth, the reasons behind why people have stopped looking for work are still poorly understood and require further research. For example, it’s difficult to estimate how many of the people who have dropped out of the workforce can ever be encouraged back into it.

In other words, uncertainty in this area abounds.

Quits

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics collects what some might find to be an odd set of data – the number of workers quitting their jobs.

Though it might seem an odd thing to look at, it is actually an important indicator of the health of a job market. For example, if the labour market is weak you would expect very few people to be voluntarily leaving their jobs as the number of opportunities elsewhere is likely to be limited.

Conversely, in a healthy job market you should see a relatively high number of people choosing to move between jobs for better pay, more exciting work or just for a change.

In May, a report by the US government showed that the three-month quit rate for non-government jobs rose to 6.6%, its highest level since 2008. Given that quits are seen as a leading indicator for wages, this gave many analysts the impression that strong income growth for workers could be just around the corner.

But is that necessarily so?

By itself, a higher rate of quits hints at a tightening of the labour market as employers are forced to compete to attract workers. As the number of available workers shrinks, employers have historically had to entice them by offering higher salaries, driving up wage growth.

Yet that very much depends on how much hidden slack, or “underemployment”, there is the job market. This would include people wanting to work more hours than they are currently offered or those classed as inactive who would seek employment if opportunities were available.

An interesting side note here is that the rate of quits has been declining since the 1980s in the US, according to a recent paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Given that job churn is how the majority of workers make the transition from low-to-mid and mid-to-high wage jobs, this could be something of a concern in terms of social mobility.

Wages

Since the beginning of the US recovery in the aftermath of the Great Recession, one of the biggest disappointments has been the pace of wage growth for American workers.

Despite the unemployment rate dropping, substantial real income gains have remained a distant prospect for much of the workforce, with hourly compensation rising at a modest average annual rate of around 2% through the recovery.

More recently there have been signs that wages might be starting to pick up, suggesting (in Yellen’s words) that “the objective of full employment is coming closer into view”. At present, however, these signs of wage pressures are tentative and hardly make a solid case for an imminent need to tighten policy.

The question now is whether, as wages rise, more people who appear to have left the labour market become tempted to jump back in. If a large number of economically inactive people suddenly start to search for jobs, then it could hold back the pace of hourly earnings growth across the economy.

Have you read?

How does the minimum wage affect jobs?

Will emerging markets weather the Fed tightening?

How labour standards affect employment

Author: Tomas Hirst is editorial director and co-founder of Pieria magazine and was previously commissioning editor, digital content at the World Economic Forum.

Image: US Federal Reserve Board Chair Janet Yellen delivers her semi-annual report on monetary policy before the Senate Banking and Urban Affairs Committee, on Capitol Hill in Washington, July 16, 2015. REUTERS/Mike Theiler

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Naoko Tochibayashi

July 30, 2025

Matt Watters

July 29, 2025

David Elliott

July 28, 2025

Michael Wang

July 28, 2025

Ivan Shkvarun

July 25, 2025

John Letzing

July 24, 2025