Can Abenomics revive Japan’s economy?

Stay up to date:

ASEAN

Since the commencement of Abenomics in 2013, Japan has become a testing ground for economic theories about how to revive a flagging economy through large-scale central bank and government stimulus.

The aim of the project was fourfold: ending deflation, raising growth, securing the sustainability of government debt, and maintaining the stability of the financial sector.

The tools at Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s disposal were additional government borrowing and spending to boost economic activity, thoroughgoing structural reforms to put the country’s finances onto a sustainable path in the long term and, crucially, to convince the traditionally inflation-shy Bank of Japan (BoJ) to significantly ease monetary policy, both through a large-scale asset purchase plan and by setting a higher inflation target.

To his credit, Abe has been able to bring all of these tools to bear as he seeks to pull Japan out of its decades-long stagnation. However, whether he will ultimately be successful still depends on how credible the Japanese people believe his reforms are and whether they alter their behaviour in response to them.

Here’s how it’s been going so far:

The quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) programme launched by the BoJ has been done at a scale not seen elsewhere in the world to date, with government bond purchases increased from ¥50 trillion a month to ¥80 trillion (or around 1% of GDP).

Indeed, according to a recent IMF working paper the BoJ “held about a quarter of the market at end-2014. But, at the current pace, it will hold about 40% of the market by end-2016 and close to 60% by end-2018.”

On some levels there do appear to have been results. After years of stagnation, the Japanese economy is beginning to show signs of life. Having taken a sharp knock following a sales tax hike in April last year, growth was revised sharply higher in the first quarter of 2015 to an annualized 3.9%. That follows a 1.5% rise in the last quarter of 2014.

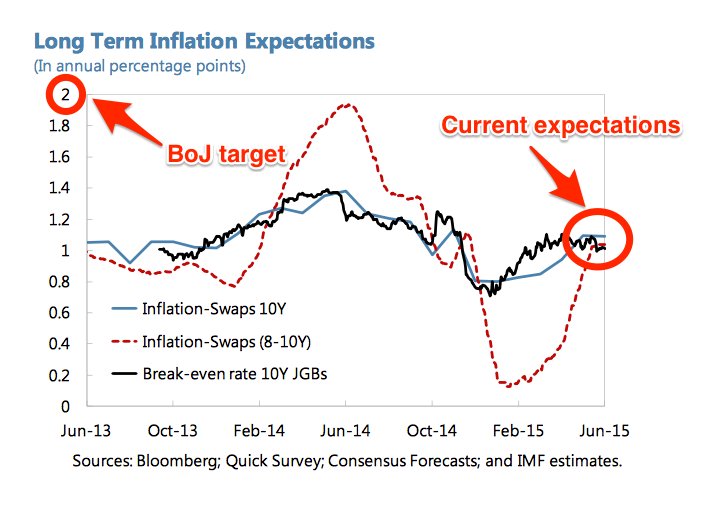

Yet its impact on headline inflation expectations in the country has so far been muted. After rising initially, measures of inflation expectations in Japan have converged around 1% – well below the BoJ’s 2% target: Shifting expectations of rising prices is considered crucial to encourage Japanese consumers to start spending, businesses to invest and erode the real value of the country’s mountainous sovereign debt burden.

Shifting expectations of rising prices is considered crucial to encourage Japanese consumers to start spending, businesses to invest and erode the real value of the country’s mountainous sovereign debt burden.

Where Abenomics has had an impact is on the cost of capital, with interest rates in Japan falling significantly in response to the brute force purchases by the central bank. Just as in the US and UK experience, however, this has not led to a significant pick-up in bank lending to the real economy.

Instead, the transmission mechanism of QQE to the real economy appears heavily reliant on the portfolio rebalancing and exchange-rate channels. In June the Japanese yen fell to 125 to the dollar, pushing it to a 13-year low, and has since remained hovering around that level – although exports have yet to respond strongly to the boost in competitiveness this has provided.

Moreover, there are limits to how much more the central bank can continue to shoulder the burden of Abenomics. In particular, the rate of asset purchases is quickly reducing the amount of JGBs on Japanese bank-balance sheets, and if continued at the current pace risk limiting the supply of “safe assets” that are crucial to the efficient functioning of the financial sector.

Already, JGB holdings as a share of total assets held by Japanese banks has declined from around 20% before the advent of Abenomics to around 15% today. Once it starts to hit the 5% range it could start posing financial stability issues as the Bank of Japan soaks up an ever greater share of available government bonds. As the authors of the IMF working paper write:

We consider this level to be a minimum amount to satisfy their collateral needs, given the size of repo and derivative markets in Japan. It is also on the lower end of the range of sovereign bond holdings by banks in other G7 economies and the minimum level of JGBs held by Japanese banks historically since 1980s.

So are Japanese policy-makers out of ammunition? The short answer is no. For a start, while the government has undertaken some of the economic reforms promised by Abenomics (such as raising the sales tax) they are far from having completed them.

Prominent among the reforms that they have yet to broach are significant labour-market reforms (to allow more skilled foreign workers into the country) and scope to use more flexible labour contracts, both of which should improve productivity.

The central bank could look to shift its purchases towards longer dated government bonds, much as the Federal Reserve did in its so-called Operation Twist. That way it could continue to drive the portfolio rebalancing of insurance and pension funds, which are significantly underweight equities relative to their international peers.

The BoJ could also increase its purchases of alternative assets to JGBs. Since 2010 the BoJ has been making large-scale purchases of Japanese stocks through exchange-traded funds in an effort to tempt domestic investors into the market and increase their risk appetite.

Currently, the market value of the ETFs held by the BOJ is estimated to be around 8.6 trillion yen – which amounts to some 2% of the total value of Japanese stocks if you include bank equity taken on at the start of the 2000s. Yet there is no absolute reason why it could continue to ramp up its investments in that sector.

We remain a long way away from the end of Abenomics.

Have you read?

Can Abenomics succeed?

How will Japan shape Asia’s economy?

How Japan is managing its debt

Author: Tomas Hirst is editorial director and co-founder of Pieria magazine and was previously commissioning editor, digital content at the World Economic Forum.

Image: A boy is seen during New Year celebrations at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo January 2, 2009. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025