Can technology alone drive social change?

Stay up to date:

Media, Entertainment and Information

The use of social media and related technologies in the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street and the so-called ‘colour revolutions’ raise a number of questions. How much does the diffusion of radical ideas depend on technology itself? What role do openness and competition in media markets play? And how do the implications of new technologies and of competition depend on the initial institutional conditions?

Evidence from European history suggests that competition and openness in the media are crucial – and may have their biggest effects where political freedom is most limited.

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation is a canonical example of the way that innovative media technologies may drive profound social change.

The technology at the heart of the Reformation was the printing press. The Reformation was the first mass movement to use the new technology and the first successful challenge to the quasi-monopoly of the Catholic Church.

In 1517, Martin Luther circulated his famous theses calling for reform within the Catholic Church. Almost immediately, the ideas of the Protestant Reformation began to spread in the media across cities in German-speaking Europe.

As Protestant ideas spread in the media, citizens’ movements emerged calling for reforms in church doctrine and an end to various forms of corruption. These urban movements were popular and largely middle class. They developed without the support of local princes and challenged the authority of city councils and urban elites, with civil disobedience, preaching, marches, and street theatre (Cameron 1991).

Where the reformers won power at the municipal level, they cemented their victories in new legal institutions. In Steven Ozment’s (1975) words, “The revolutionary program came to rest in an established religion; the pamphlet became a church ordinance… the new Protestant institutions persisted.”

It commonly suggested that without printing there would have been no Reformation. ‘No printing, no Reformation’ in Bernd Moeller’s famous aphorism (1979). But literacy rates were low even in cities – perhaps 30% – leading some scholars to argue that the conventional case for the role of new media should be qualified (Scribner 1994).

The research challenge

No research has systematically documented the diffusion of Protestant ideas in the media during the Reformation in quantitative terms. This is because the data on the media are large and complicated. There are thousands of publications – in historical German – by unknown authors. While about a third of publications from the 1500s were on religious topics, no existing data systematically classify the content or religious persuasion of this media.

Moreover, to study how technology and competition shaped diffusion, we need evidence on firms and media markets – which previously has not been constructed.

Documenting the diffusion of ideas in the media – high dimensional data

In new research, we construct a novel measure of religious content in the media (Dittmar and Seabold 2015). We examine all known books and pamphlets produced in German-speaking Europe 1450-1600 – over 108,000 individual publications produced in over 100 cities.

We construct a measure of religious content by using statistical methods for high dimensional data. A large literature uses statistical models to study sentiment and ideology in the language of twitter ‘tweets’ and of contemporary news media (e.g., Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010, Taddy 2013). We take these models for text data to the historical evidence from the Reformation and obtain an index of content.

Figure 1 presents the big picture from the aggregate time series. Following Martin Luther’s first intervention in 1517, we see a discontinuous shift in the religious content of the media, away from Catholic (0) towards Protestant (1). This shift is observed in both German and Latin religious media. We also observe a sharp increase in the number of religious publications in the vernacular – as captured by the scale of the markers in the graph.

Figure 1. Index of religious content in the media

Determinants of diffusion

There are two big arguments in the historical literature. The first is that printing was absolutely critical to the diffusion of the Reformation. The second is that cities with constitutionally protected political freedoms played a key role in the movement’s development. The institutional distinction here is between the two principal types of cities formally recognised by the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire. In ‘free cities’, city councils had extensive policy autonomy. In the cities that were not ‘free’, citizens and municipal authorities fell under the legal jurisdiction of the local feudal lord.

The existing literature suggests that political freedom and the press were together behind the Reformation. Our evidence suggests a different and more nuanced picture, in which the economics of the media interacted with prior political institutions.

We find that cities with more competitive markets saw a much greater diffusion of the Reformation in the media. Moreover, this competition effect is even stronger in the cities that fell under the rule of local lords – where otherwise existing institutions placed the greatest barriers before the diffusion of radical ideas and movements.

Evidence on competition and radical ideas

Historians have suggested that competition mattered. Andrew Pettegree (2000) observes that, “Where a market was controlled, the free flow of innovative theological speculation was greatly inhibited.”

We test this argument by constructing data on every firm operating in central Europe. We construct the data by examining the inscriptions that record the printer producing each individual book and pamphlet in our data, and cross-check these output based measures against records from biographical dictionaries of printers.

We then study how city-level market structure on the eve of the Reformation explains subsequent diffusion. We find that cities with more firms saw more Protestant media – even controlling for the overall size and composition of their media output prior to Reformation. We study over 190 cities and towns. Of these, 55 had printing before 1517 and the median city with printing on the eve of the Reformation had two firms active.

We find an additional firm just before the Reformation was associated with about a 20% increase in Protestant content. Moreover, Protestant content really increases when we compare cities with two or three firms to cities with no printing or simply a local monopoly.

Figure 2 illustrates this point by documenting the non-linear relationship between Protestant media and the initial number of firms (here we examine residual Protestant media, taking out variation explained by city size, prior religious output, the language composition of pre-Reformation output, and measures of local institutions).

Figure 2. Protestant ideas in the media and pre-Reformation competitors

Did variations in competition cause differences in diffusion?

The obvious question is whether cities with more competitive media markets had other characteristics that made them receptive to reformist ideas. Maybe these cities were always more open to innovation? Or maybe these cities were experiencing new forms of cultural and economic dynamism just before the Reformation – inducing firms to enter and simultaneously predisposing them towards the coming religious innovations?

To isolate variations in market structure that are plausibly free of these forms of reverse causation we do two things. First, we study variations in competition that were induced by the chance timing of the deaths of master printers – which were independent of the more slow moving characteristics that may have made some cities more receptive to religious innovation than others.

Second, we study variations in competition that reflect longer run differences in city market structure and do not embody endogenous entry on the eve of the Reformation. Our results examining these two plausibly random sources of variation in market structure both support the view that competition was a key predictor of diffusion.

Institutional change

The Protestant Reformation led to formal institutional change. These changes occurred first at the city level. Where reformers won power, city councils created new legal institutions, beginning in the 1520s. The new laws reformed church governance and social welfare provision and established the most ambitious early experiments in mass public education in European history.

Previous research in economics has not examined these formal institutional changes. We code up which cities got the legal ordinances of the Reformation and then study the relationship between competition, exposure to content, and legal change.

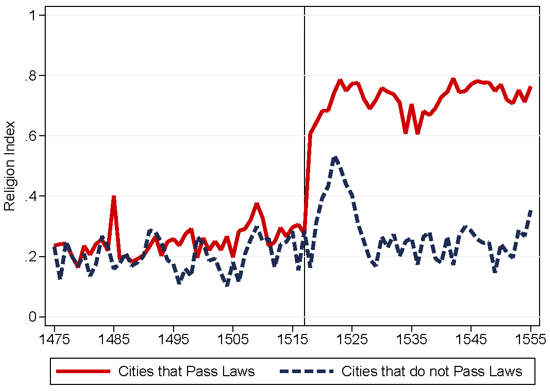

Figure 3 shows that most of the legal innovation occurred before the mid-1500s. In the mid-1500s, first military conflict, and then the new institutional equilibrium settled in law by the Peace of Augsburg (1555), arrested the diffusion of Protestantism.

Figure 4 maps the geography of municipal legal reform. Figure 5 shows that cities that did and did not change legal institutions had similar religious media before the Reformation and that there were no clear trends before 1517.

Figure 3. The laws of the Reformation

Figure 4. Legal Reformation across Cities 1518-1554

Figure 5. Religious content for cities that do and do not pass Reformation laws

Determinants of institutional change

We find that variations in initial competition in media markets strongly predict legal change in cities that were under the jurisdiction of authoritarian feudal lords. In contrast, in the free cities, the relationship between prior competition and legal change is relatively weak. This evidence strongly suggests that competition in the media mattered most where citizens and policymakers otherwise faced the largest barriers to mobilisation and social change.

It is important to underline here that the media were used to galvanise citizens’ movements, which faced free rider problems and were challenging religious and secular elites. The constituency for reform came from citizens who were excluded from political power by oligarchic elites, typically lesser merchants and guild members (Ozment 1975, Schilling 1983).

Cameron (1991) observes that, “As a rule neither the city patricians nor the local princes showed any sympathy for the Reformation in the crucial period in the late 1520s and early 1530s; they identified themselves with the old Church hierarchy and accordingly shared its unpopularity. Popular agitation on a broad social base led to the formation of a ‘burgher committee’.”

This model notably characterised the Reformation in its birth place – “It is undeniable that the Wittenberg movement was borne on a wave of popular enthusiasm. It outran the city magistrates’ ability to control it, and finally forced them to act even against the will of the Elector [the territorial ruler of Wittenberg], who had prohibited any innovations in church matters” (Scribner 1979; p. 53).

Why competition mattered

While producers were motivated by belief, printing was a competitive business in which religion was a dimension for product differentiation. In cities with just a local monopolist that printer was de facto or de jure the ‘city printer’. Faced by an adversarial monopolist, city councils might encourage a new entrant. In cities with multiple printers, one printer was typically the official city printer (ratsbuchdrucker) and the rest were not.

The fact that known city printers were not early advocates of the Reformation is consistent with the view that they did not want to endanger official work orders or antagonise city governments, while outsiders may not have been so constrained.

The big picture for economics

An influential body of scholarship traces differences in contemporary economic performance and behaviour to historically determined institutions or beliefs (Acemoglu et al 2001, 2011; Voigtlander and Voth 2012; Guiso et al 2003). This literature raises the question – What explains the dynamics of fundamental institutional change?

The Reformation interests us as arguably one of the most important changes in social institutions of the last several centuries.

We specifically study environments in which the media were used to solve free rider problems and mobilise citizens’ movements that aimed to transform social institutions.

Our key findings suggest that the diffusion of the Reformation was not driven by information technology acting alone. We find that competition in media markets mattered. In the cities where political freedom was most limited – where the legal prerogatives of authoritarian rulers were greatest – competition and openness in the media delivered their biggest effects.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J Robinson (2001) “The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation,” The American Economic Review, 91(5): 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D, D Cantoni, S Johnson, and J Robinson (2011) “The consequences of radical reform: The French revolution,” The American Economic Review, 101: 3286–3307.

Dittmar, J and S Seabold (2015) “Media, markets and institutional change: The Protestant Reformation”.

Cameron, E (1991) The European Reformation, Clarendon Press.

Gentzkow, M and J M Shapiro (2010) “What drives media slant? Evidence from US daily newspapers”, Econometrica, 78(1): 35–71.

Guiso, L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2003) “People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes”,Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1): 225-282.

Moeller, B (1979) “Stadt und Buch”, in W Mommsen (ed), Stadtburgertum und Adel in der Reformation, Stuttgart. Ernst Klett.

Ozment, S E (1975) The Reformation in the Cities: Appeal of Protestantism to Sixteenth Century Germany and Switzerland, volume 357, Yale University Press.

Pettegree, A (2000) The Reformation World, Routledge.

Schilling, H (1983) “The Reformation in the Hanseatic cities”, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 14(4): 443–456.

Scribner, R W (1979) “The Reformation as a social movement”, in W Mommsen (ed),Stadtburgertum und Adel in der Reformation, Stuttgart. Ernst Klett.

Scribner, R W (1994) For the sake of simple folk: Popular propaganda for the German Reformation, Oxford University Press.

Taddy, M (2013) “Measuring political sentiment on Twitter: Factor optimal design for multinomial inverse regression”.

Voigtlander, N and H-J Voth (2012) “Persecution perpetuated: The medieval origins of anti-semitic violence in Nazi Germany”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3): 1339-1392.

This article is published in collaboration with VoxEU. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Authors: Jeremiah Dittmar is a Professor of Economics, London School of Economics. Skipper Seabold is a Ph.D candidate in economics and econometrics, American University; Data Scientist, Civis Analytics.

Image: A man types on a computer keyboard in Warsaw in this February 28, 2013 illustration file picture. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel/Files.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Elena Fersman

May 14, 2025

Rya G. Kuewor

May 13, 2025

Tea Trumbic and Dhivya O’Connor

May 13, 2025

Anurag Sinha

May 9, 2025

Jake Okechukwu Effoduh

May 7, 2025