The rise of the renminbi

China’s impressive economic expansion of recent decades has seen it quickly rise through the ranks of the world’s largest economies. Only the US currently stands between it and the top spot.

With its increasing size and importance to global trade has come greater focus on the country’s currency policies.

Since 2005 the Chinese authorities have attempted to loosen the renminbi’s peg to the dollar, which it instituted in 1994, in an effort to move the economy away from its reliance on exports and towards a more balanced mix of domestic and foreign demand for its goods and services.

To date that process has been gradual.

After allowing the currency to appreciate against the dollar from July 2005 to make it “adjustable, based on market supply and demand with reference to exchange rate movements of currencies in a basket”, it then reinstated the peg in July 2008 to mitigate some of the impact of the global financial crisis. It began appreciating again from June 2010, climbing 16.9% against a trade-weighted basket of other currencies by May 2013.

However, it hasn’t all been one-way traffic. Last year China’s currency fell 2.5% against the dollar – only its second fall since 2005 – and since then the renminbi has repeatedly tested the lower bound of its range.

So what’s going on?

The first major point is that growth in China is slowing (albeit from significantly higher rates of growth than the West). This has dampened investor enthusiasm over the country for the time being, with money beginning to flow out.

Meanwhile the US dollar has surged, climbing 13% against a trade-weighted basket of currencies over the six months to the end of March:

Exacerbating this trend, there is a growing divergence in interest rate trajectories between Beijing and Washington. The US Federal Reserve is preparing for a “lift-off” of rates later this year and China is grappling with a property slump and doubts over the health of its financial sector linger in the wake of both a real estate and leveraged stock market boom/bust cycle.

Thirdly, there are concerns that the rapid appreciation of the renminbi over recent years has simply gone too far and the currency is now overvalued (or at least the consensus that it is undervalued has been shaken). If the market is seeking to find a new “fair value” for the currency then some volatility is to be expected. As Bruegel put it in a recent blogpost:

Even allowing for fast Chinese productivity growth, there are now questions about whether the RMB is already fairly valued or even somewhat overvalued. Simply put, the once broad-based market consensus of an undervalued RMB is gone, after its massive cumulative appreciation.

Are renminbi falls a big problem for China?

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco points to Chinese companies’ foreign debt burdens as a possible source of concern with a combination of a rising dollar and slowing domestic growth. As Sean Creehan put it in a blogpost last month:

China, the region’s largest economy, has seen its external debt rise with large inflows of so-called “hot money” to higher-yielding Mainland assets. UBS estimates that as of the end of 2014, Chinese companies had issued roughly $1 trillion in unhedged foreign debt – equivalent to over 10% of GDP – as part of this carry trade. While the renminbi has a narrow trading band against the dollar, continued financial sector reform may involve further liberalization of the renminbi and capital account, putting stress on foreign debt service.

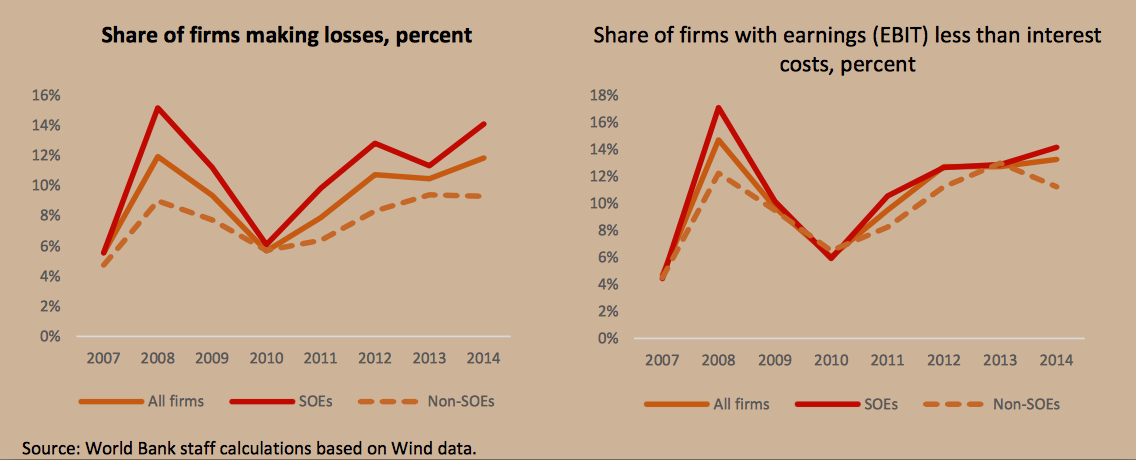

In other words, as the renminbi weakens versus the dollar it becomes more and more expensive to service dollar-denominated debts. Furthermore, an increased share of listed companies in China are already struggling to turn a profit, with some seeing interest paid on debt higher than total earnings (according to the World Bank):

These trends paint an uncertain picture for the near-term future of China’s currency. Historically, the authorities have responded to periods of foreign exchange volatility by tightening the renminbi’s peg to the dollar to dampen its effects on the real economy.

On this occasion, however, not everyone is convinced that this would be the right course to follow.

As Guonan Ma argues at Bruegel, allowing the exchange rate to remain flexible against the dollar while intervening by selling dollar reserves to manage the transition potentially offers a number of benefits. Chief among these is that it could provide the country with some additional monetary loosening to help boost the domestic economy by lowering the cost of renminbi capital and, secondly, allow for “an orderly unwinding of the Chinese corporate carry trade”.

Secondly, despite capital outflows hitting an all-time high of $3.99 trillion in June last year we don’t (yet) have a good understanding of what is driving them or how far there might yet be to go. The big question is whether the flows represent foreign sellers of Chinese assets (for example, a repatriation of capital to the US on expectations of higher interest rates) or domestic outflows (e.g. an unwinding of FX liabilities of Chinese companies and a build up of dollar currency reserves).

In the former case, the current bout of outflows should not be much different to the hot money flows that China has seen in the past and the downward pressure being exerted on the renminbi should ultimately abate (at the current pace of outflows of around $200 billion annualized, a large proportion of foreign positions in RMB could have been unwound as early as the end of the year). If the latter, however, significant further intervention by the state could be warranted to defend the currency from a depreciation spiral.

As the FT’s David Keohane writes:

Maybe what is going on, as JPM’s Zhu argues, is a regime change in its balance of payments composition, one that appears to be largely intentional and policy-driven as the RMB internationalizes and China reaches out via OBOR and the like. Perchance, as UBS say, the outflows will moderate. But, obviously, they might not.

This will be a key story to watch.

Have you read?

China and Greece: a tale of two crises

How can China find new routes to growth?

Can China tackle its debt challenge?

Author: Tomas Hirst is editorial director and co-founder of Pieria magazine and was previously commissioning editor, digital content at the World Economic Forum.

Image: Chinese 100 yuan banknotes are seen in this picture illustration taken in Beijing July 11, 2013. China’s central bank has standardised rules on cross-border yuan transactions for domestic banks and companies, the latest step to boost the yuan’s global influence. REUTERS/Jason Lee

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

ASEAN

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Rishika Daryanani, Daniel Waring and Tarini Fernando

November 14, 2025