Why it’s time to turn off the money tap

Stay up to date:

Financial and Monetary Systems

It’s common knowledge that low-income households have paid a high price for the 2008 financial crisis. This, in turn, is fuelling the debate that the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

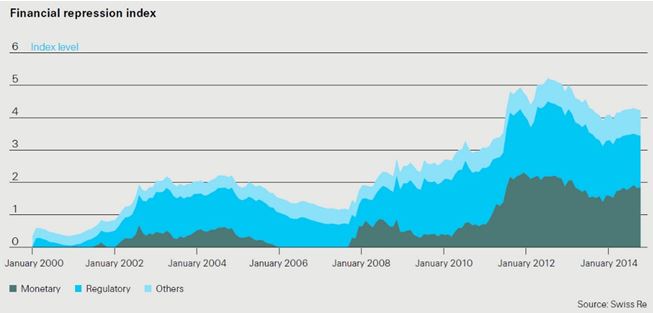

To manage the crisis, central banks applied unconventional official policies. They turned on the money tap and lowered interest rates – with severe consequences. Governments and wealthy households have profited, while savers have been punished. Today, seven years after the onset of the crisis, these policies – called “financial repression” – still remain close to a record high.

If that is not changed quickly, we will see increasing economic inequality and widespread social and financial instability.

It’s a rich man’s world

The equity rally – one of the market imbalances resulting from the financial crisis – has benefited wealthier people, who tend to invest more of their money in equities. Unfortunately, these “paper profits” have not contributed to additional consumption or real economic growth.

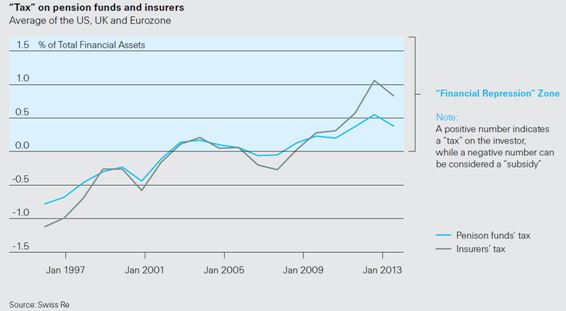

As if that was not enough, savers have been penalized. Unorthodox policies that are keeping interest rates low mean they lose out on interest income. In other words, they pay an “invisible tax”. In the case of negative interest rates, such as in Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark, some people are actually charged to keep their money in the bank. The costs of financial repression have been quantified in a Swiss Re report, Financial repression: The unintended consequences.

The war on savings

Since the crisis, the invisible tax has cost US households a whopping $670 billion in foregone interest income. Relative to GDP, this tax is largest in the UK at around 9%, smallest in Germany at around 3% and around 4% in the US.

These are big numbers. Let me be more concrete: put yourself in the shoes of a 50-year-old who is soon planning to retire with a monthly annuity of $3,000. In the current environment, you will need to start saving $700 to $800 more each month compared to a normal interest rate environment. That means you either have to spend less, work longer or settle for a lower annuity.

It’s a vicious cycle. The need to increase savings has further weakened consumption growth, resulting in poor economic recovery and adding to the excess of cash in search of yield. What’s more, future generations will have to shoulder the costs – including the underfunding of pension provisions. When will policy-makers start thinking long-term?

Putting institutional money back to work

Prevailing low interest rates have also had a profound impact on institutional investors’ portfolio returns. Given their business need to match long-term liabilities, they hold a significant part of their assets in fixed income securities. The depressed returns have cost EU and US insurers around $500 billion in foregone investment yield income since 2008. For consumers, this could eventually translate into higher premiums.

Even more concerning, current public intervention is crowding long-term investors out of the markets. It prevents them from moving saving funds to the real economy. Less money is put to work in growth-enhancing investments, such as infrastructure, which would create jobs and, ultimately, help safeguard financial stability and economic growth at large.

Three policy wishes, one sustainable global economy

So, how can we put institutional money back to valuable work? Three things need to be done to protect our financial future: we need to strengthen private capital market intermediation; the public sector must team up with the private sector to support the development of tradable asset classes; and the public sector must enable long-term investors to act on a long-term horizon. We must put an end to short-termism! The economy belongs to all of us. Soon it will belong to our children. It’s time to strengthen financial market stability, which is so important for making it sustainable.

Have you read?

Why the panic over China’s markets?

Why is inflation falling everywhere?

Author: Martyn Parker, Chairman, Global Partnerships, Swiss Re, UK

Image: Venezuelan bolivar banknotes and a U.S. dollar banknote, folded as boats, are seen at a fruit and vegetable store in Caracas July 10, 2015. REUTERS/Marco Bello

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Respectful national partnerships key to achieving impact and efficiency in international development

Ruth Goodwin-Groen, Pia Bernadette Roman Tayag, Hinjat Shamil and Tidhar Wald

May 5, 2025

Ana Mahony

April 30, 2025

Graham Pearce

April 30, 2025

Rebecca Geldard

April 29, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025