Why is US inflation so low?

Stay up to date:

Economic Progress

Remarks given by Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer at the Economic Policy Symposium hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, on 29 August 2015.

I am delighted to be here in Jackson Hole in the company of such distinguished panelists and such a distinguished group of participants.

I will focus my remarks today on forces–domestic and international–that have been holding down inflation in the United States,1 and some of the consequences of recent–primarily international–developments.

Although the economy has continued to recover and the labor market is approaching our maximum employment objective, inflation has been persistently below 2 percent. That has been especially true recently, as the drop in oil prices over the past year, on the order of about 60 percent, has led directly to lower inflation as it feeds through to lower prices of gasoline and other energy items. As a result, 12-month changes in the overall personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index have recently been only a little above zero (chart 1).

The past year’s energy price declines ought to be largely a one-off event (chart 2). That is, while futures markets suggest that the level of oil prices is expected to remain well below levels seen last summer, markets do not expect oil prices to fall further, so their influence in holding down inflation should be temporary. But measures of core inflation, which are intended to help us look through such transitory price movements, have also been relatively low (return to chart 1). The PCE index excluding food and energy is up 1.2 percent over the past year. The Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean measure of the PCE price index is higher, at 1.6 percent, but still somewhat below our 2 percent objective. Moreover, these measures of core inflation have been persistently below 2 percent throughout the economic recovery. That said, as with total inflation, core inflation can be somewhat variable, especially at frequencies higher than 12-month changes. Moreover, note that core inflation does not entirely “exclude” food and energy, because changes in energy prices affect firms’ costs and so can pass into prices of non-energy items.

Inflation as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) generally sends the same broad message as does the PCE price index (chart 3). That similarity should not be surprising, because the CPI is the most important input used for constructing PCE prices. On average, CPI inflation tends to run a few tenths higher than PCE inflation, and, because the CPI has a modestly larger weight on energy prices, fluctuations in the CPI measure tend to be a bit larger.

Of course, ongoing economic slack is one reason core inflation has been low. Although the economy has made great progress, we started seven years ago from an unemployment rate of 10 percent, which guaranteed a lengthy period of high unemployment. Even so, with inflation expectations apparently stable, we would have expected the gradual reduction of slack to be associated with less downward price pressure. All else equal, we might therefore have expected both headline and core inflation to be moving up more noticeably toward our 2 percent objective. Yet, we have seen no clear evidence of core inflation moving higher over the past few years. This fact helps drive home an important point: While much evidence points to at least some ongoing role for slack in helping to explain movements in inflation, this influence is typically estimated to be modest in magnitude, and can easily be masked by other factors.2

In the first instance, as already noted, core inflation can to some extent be influenced by oil prices. However, a larger effect comes from changes in the exchange value of the dollar, and the rise in the dollar over the past year is an important reason inflation has remained low (chart 4). A higher value of the dollar passes through to lower import prices, which hold down U.S. inflation both because imports make up part of final consumption, and because lower prices for imported components hold down business costs more generally. In addition, a rise in the dollar restrains the growth of aggregate demand and overall economic activity, and so has some effect on inflation through that more indirect channel.3

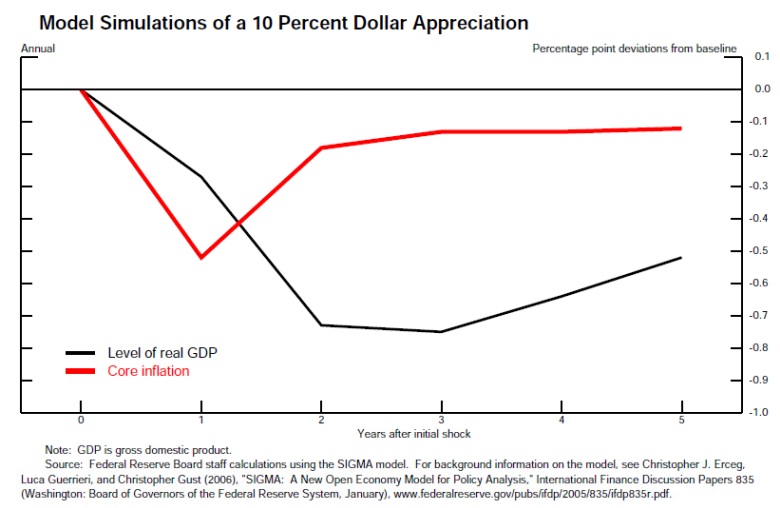

To get a sense of the timing and magnitude of these exchange rate effects, chart 5 shows dynamic simulations of a 10 percent real dollar appreciation, based on one of the models we maintain at the Federal Reserve.4 The estimated pass-through from import prices to consumer price inflation occurs relatively quickly, with effects becoming evident within a quarter and the bulk of the overall effect occurring within one year. By contrast, the portion of the dollar effects on inflation that work through the channel of overall economic activity occurs with considerable lags. In the model shown here, the appreciation has its largest effect on gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the second year after the shock. Thus, it is plausible to think that the rise in the dollar over the past year would restrain growth of real GDP through 2016 and perhaps into 2017 as well. The rise in the dollar since last summer, of about 17 percent in nominal terms, with its associated declines in non-oil import prices, could plausibly be holding down core inflation quite noticeably this year.

Commodity prices other than oil are also of relevance for inflation in the United States. Prices of metals and other industrial commodities, and agricultural products, are affected to a considerable extent by developments outside the United States, and the softness we’ve seen in these commodity prices, has in part reflected a slowing of demand from China and elsewhere. These prices likely have also been a factor in holding down inflation in the United States.

The dynamics with which all these factors affect inflation depend crucially on the behavior of inflation expectations. One striking feature of the economic environment is that longer-term inflation expectations in the United States appear to have remained generally stable since the late 1990s (chart 6). The source of that stability is open to debate, but the fact that the Fed has kept inflation relatively low and stable for three decades must be an important part of the explanation. Expectations that are not stable, but instead follow actual inflation up or down, would allow inflation to drift persistently. In the recent period, movements in inflation have tended to be transitory. For example, one might have expected the Great Recession to generate a downward wage-price spiral, but this did not occur. Thus, the stability of inflation expectations has prevented inflation from falling further below our objective than occurred, and it has enabled the Federal Open Market Committee to look through some upward inflation shocks without compromising price stability.5

We should however be cautious in our assessment that inflation expectations are remaining stable. One reason is that measures of inflation compensation in the market for Treasury securities have moved down somewhat since last summer (chart 7). But these movements can be hard to interpret, as at times they may reflect factors other than inflation expectations, such as changes in demand for the unparalleled liquidity of nominal Treasury securities.

In announcing its July interest rate decision, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) said:

In determining how long to maintain this target range, the Committee will assess progress–both realized and expected–toward its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. The Committee anticipates that it will be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it has seen some further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term.

Can the Committee be “reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term”? As I have discussed, given the apparent stability of inflation expectations, there is good reason to believe that inflation will move higher as the forces holding down inflation dissipate further. While some effects of the rise in the dollar may be spread over time, some of the effects on inflation are likely already starting to fade. The same is true for last year’s sharp fall in oil prices, though the further declines we have seen this summer have yet to fully show through to the consumer level. And slack in the labor market has continued to diminish, so the downward pressure on inflation from that channel should be diminishing as well.

In addition, with regard to expectations of inflation, it is possible to consult the results of the SEP, the Survey of Economic Projections, which FOMC participants complete shortly before the March, June, September, and December meetings. In the June SEP, the central tendency of FOMC participants’ projections for core PCE inflation was 1.3 percent to 1.4 percent this year, 1.6 percent to 1.9 percent next year, and 1.9 percent to 2.0 percent in 2017. There will be a new SEP for the forthcoming September meeting of the FOMC.

Reflecting all these factors, the Committee has indicated in its post-meeting statements that it expects inflation to return to 2 percent. With regard to our degree of confidence in this expectation, we will need to consider all the available information and assess its implications for the economic outlook before coming to a judgment.

In addition, the July announcement set a condition of requiring “some further improvement in the labor market.” From May through July, non-farm payroll employment gains have averaged 235,000 per month. We now await the results of the August employment survey, which are due to be published on September 4.

Of course, the FOMC’s monetary policy decision is not a mechanical one, based purely on the set of numbers reported in the payroll survey and in our judgment on the degree of confidence members of the committee have about future inflation. We are interested also in aspects of the labor market beyond the simple U-3 measure of unemployment, including for example the rates of unemployment of older workers and of those working part-time for economic reasons; we are interested also in the participation rate. And in the case of the inflation rate we look beyond the rate of increase of PCE prices and define the concept of the core rate of inflation.

While thinking of different aspects of unemployment, we are concerned mainly with trying to find the right measure of the difficulties caused to current and potential participants in the labor force by their unemployment. In the case of the core rate of inflation, we are mainly looking for a good indicator of future inflation, and for better indicators than we have at present.

In making our monetary policy decisions, we are interested more in where the U.S. economy is heading than in knowing whence it has come. That is why we need to consider the overall state of the U.S. economy as well as the influence of foreign economies on the U.S. economy as we reach our judgment on whether and how to change monetary policy. That is why we follow economic developments in the rest of the world as well as the United States in reaching our interest rate decisions. At this moment, we are following developments in the Chinese economy and their actual and potential effects on other economies even more closely than usual.

The Fed has, appropriately, responded to the weak economy and low inflation in recent years by taking a highly accommodative policy stance. By committing to foster the movement of inflation toward our 2 percent objective, we are enhancing the credibility of monetary policy and supporting the continued stability of inflation expectations. To do what monetary policy can do towards meeting our goals of maximum employment and price stability, and to ensure that these goals will continue to be met as we move ahead, we will most likely need to proceed cautiously in normalizing the stance of monetary policy. For the purpose of meeting our goals, the entire path of interest rates matters more than the particular timing of the first increase.

With inflation low, we can probably remove accommodation at a gradual pace. Yet, because monetary policy influences real activity with a substantial lag, we should not wait until inflation is back to 2 percent to begin tightening. Should we judge at some point in time that the economy is threatening to overheat, we will have to move appropriately rapidly to deal with that threat. The same is true should the economy unexpectedly weaken.

Finally, while I have been talking today about some international influences on economic conditions in the United States, I am well aware that, when the Federal Reserve tightens policy, this affects other economies. The Fed’s statutory objectives are defined in terms of economic goals for the economy of the United States, but I believe that by meeting those objectives, and so maintaining a stable and strong macroeconomic environment at home, we will be best serving the global economy as well.6

1. The views expressed here are my own and not necessarily those of others at the Board, on the Federal Open Market Committee, or in the Federal Reserve System.

2. Among the many papers finding a role for resource utilization in affecting inflation based on evidence from macroeconomic time-series data, see Robert J. Gordon (2013), “The Phillips Curve Is Alive and Well: Inflation and the NAIRU during the Slow Recovery (PDF),” ![]() NBER Working Paper Series 19390 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, August); or Douglas O. Staiger, James H. Stock and Mark W. Watson (1997), “How Precise Are Estimates of the Natural Rate of Unemployment?”

NBER Working Paper Series 19390 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, August); or Douglas O. Staiger, James H. Stock and Mark W. Watson (1997), “How Precise Are Estimates of the Natural Rate of Unemployment?” ![]() in Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, eds., Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 195-246. For similar results based on cross-sectional evidence, see Michael T. Kiley (2014), “An Evaluation of the Inflationary Pressure Associated with Short- and Long-Term Unemployment (PDF),” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2014-28 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March); or, for wages instead of prices, Christopher L. Smith (2014), “The Effect of Labor Slack on Wages: Evidence from State-Level Relationships,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 2).

in Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, eds., Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 195-246. For similar results based on cross-sectional evidence, see Michael T. Kiley (2014), “An Evaluation of the Inflationary Pressure Associated with Short- and Long-Term Unemployment (PDF),” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2014-28 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March); or, for wages instead of prices, Christopher L. Smith (2014), “The Effect of Labor Slack on Wages: Evidence from State-Level Relationships,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 2).

3. There has also been debate regarding other potential channels through which global factors could affect domestic inflation–for example, whether measures of foreign resource utilization play an important independent role. For evidence supporting such global factors, see Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo (2007), “Globalisation and Inflation: New Cross-Country Evidence on the Global Determinants of Domestic Inflation (PDF),” ![]() BIS Working Papers 227 (Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements, May). For a more skeptical take, see Jane Ihrig, Steven B. Kamin, Deborah Lindner, and Jaime Marquez (2007), “Some Simple Tests of the Globalization and Inflation Hypothesis (PDF),” International Finance Discussion Papers 891 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April).

BIS Working Papers 227 (Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements, May). For a more skeptical take, see Jane Ihrig, Steven B. Kamin, Deborah Lindner, and Jaime Marquez (2007), “Some Simple Tests of the Globalization and Inflation Hypothesis (PDF),” International Finance Discussion Papers 891 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April).

4. For background information on this model, see Christopher Erceg, Luca Guerrieri, and Christopher Gust (2006), “SIGMA: A New Open Economy Model for Policy Analysis (PDF),” International Finance Discussion Paper Series 2005-835 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January). This model incorporates monetary policy responses to economic shocks and thus may show smaller effects on real GDP and inflation than other partial-equilibrium analyses. That said, the SIGMA model is just one of a number of models that the Board staff regularly consults to inform their analysis of the U.S. economy.

5. It is noteworthy that in several inflation-targeting economies, the ten year expected inflation rate has settled precisely at the target inflation rate.

6. For more discussion on this theme, see Stanley Fischer (2014), “The Federal Reserve and the Global Economy,” speech delivered at the 2014 Annual Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group, Washington, October 11.

Author: Stanley Fischer is Vice Chairman of the US Federal Reserve.

Image: US Federal Reserve Vice Chair Stanley Fischer addresses The Economic Club of New York. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

April 23, 2025