6 charts to help you become an arctic expert

Stay up to date:

Arctic

The Arctic has been described as the canary in the coalmine for the health of the global environment. It is a complex region that is experiencing unprecedented change. We are witnessing drastic environmental, economic and societal changes that not only have regional implications, but are also likely to have profound global consequences.

But how much does the average person really know about the Arctic? Here are six charts to help you become an Arctic expert.

- Where is the Arctic?

It’s not just the area around the North Pole: it covers a substantial area of the northern part of our planet. While there are many definitions for the Arctic, the most common is the territory lying north of the Arctic Circle, an imaginary line that circles the Earth at 66°33′N. It represents the southernmost latitude at which the sun remains above the horizon in summer for at least a full day, and at least a full day below the horizon during winter. The Arctic can be described as a predominately ice-covered ocean surrounded by land.

Source: Beyond Penguins

- Who owns the Arctic?

In the distant past there were not that many fights over who owned this polar ice cap. Eight countries have sovereign rights and are considered Arctic nations. These are the five that border the Arctic Ocean: Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Norway, Russia and the United States – as well as three countries whose territory lies partially north of the Arctic Circle: Finland, Iceland and Sweden. As with other regions of the world, international law states that Arctic countries are entitled to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles adjacent to their coastline. The waters beyond their EEZ are presently beyond the jurisdiction of these nations. However, this may not be the case for ever; who owns what in the Arctic is presently under renegotiation.

Under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), each country can extend its claim up to 350 nautical miles from its coastal baseline. For this to occur it must be proven beyond doubt that the sea floor is an extension of that country’s continental shelf. If successful, it gives that state control of all resources on or under the region of the continental shelf.

The economic potential of the Arctic sea floor has led to a new scramble for territory among four of the five Arctic states – namely Canada, Denmark, Norway and Russia. As of September 2015, the US had not ratified this treaty. Consequently, over the past few years there has been a lot of seafloor-mapping activity in the Arctic going on … some legal and some perhaps not.

And remember, despite these international agreements about territorial rights, indigenous peoples – who have lived in this region for many thousands of years – lay a claim to the Arctic too.

Five nations that border the Arctic Ocean and their potential ‘new’ Arctic territory:

Source: The Economist

- Arctic change

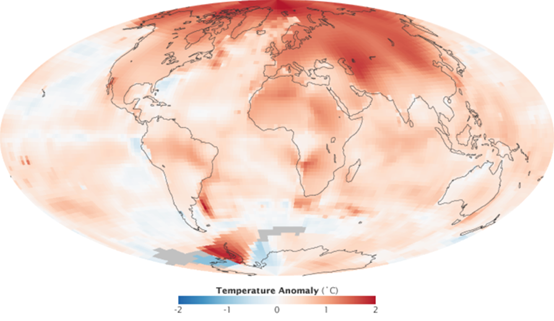

The Arctic that most of us grew up with is not the Arctic that our kids will encounter. Long-term observations have shown that Arctic temperatures are increasing faster than anywhere else on the planet. This “Arctic amplification” of global warming has led to major and quantifiable changes across the region, from the melting of glaciers and ice sheets, to the thawing of permafrost, the acidification of the ocean, and the changing of the physical environment in all regions of the Arctic, from the upper atmosphere to the deep sea. It is important to remember that Arctic change is not just about the climate and the environment; it also affects people through changes in ecosystems, societal structures and economic opportunities.

One of the most visible changes must be the Arctic summer sea ice. We have lost almost half of it in just a few decades. Furthermore, it is receding faster than projected, and is expected to virtually disappear in summer within a generation. To understand the impact of these changes, experts from many different sectors must work together. This is because the world climate and world economics are interconnected. We are becoming increasingly aware that what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic.

NASA GISS temperature trend 2000-2009, showing strong increase in the surface temperatures in the Arctic.

Source: Nasa

- Arctic natural resources

Obama’s visit to the region next week will surely highlight the fractious nature of exploiting the abundant Arctic resources. These days, all eyes are looking north.

And it’s no wonder why: the Arctic holds some of the world’s largest remaining oil and gas reserves, an enormous untapped mineral wealth, an expanding fishery, and a flourishing tourism industry. In recent years these sectors have seen growth in their Arctic portfolios and income.

As the melting of the Arctic sea ice continues, previously inaccessible regions of the Arctic Ocean are opening up to commercial and recreational activities. A recent report by Lloyds on opportunity and risk in the high north suggested that over the coming decade the Arctic is likely to attract substantial investment, potentially reaching $100 billion or more. Economic opportunities and environmental risks characterize the dichotomy that the Arctic nations, local communities and global society face in the Arctic.

The vast majority of the potential wealth of the region is held by the six nations that border the Arctic Ocean: Canada, Greenland (Denmark), Iceland, Norway, Russia and the US. However, our knowledge of the Arctic ecosystem is presently limited, and due to the sensitive nature of the Arctic environment, existing and future developments need to ensure that particular attention is paid to sustainable development as well as environmental and human sensitivities. It is certainly not going to be easy to strike this balance.

This chart shows estimates of undiscovered oil and gas north of the Arctic Circle as performed by the Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal (CARA) group. Notice that most oil (shaded brown) lies in the shallow continental shelf seas which are experiencing the largest melt of sea ice.

- Shipping routes

The abundance of accessible and “in demand” natural resources, combined with the extension of the Arctic navigation season (due to the continuing reduction of summer sea ice) has has reignited the debate regarding the viability of commercial traffic through either the Northwest Passage (via Canada) and/or the Northern Sea Route (via Russia). The shipping of commodities from Asia or western North America to northern Europe has traditionally relied on the Panama or Suez canals. Shipping via the Arctic Ocean is commercially attractive as it represents a saving in distance (hence cost) of up to 40%.

While a warmer Arctic ensures an easier transit of vessels across the Arctic Ocean in summer, there are significant hurdles to overcome before the route develops into an economically viable and sustainable shipping lane. These include:

- A substantial increase in the commodity price of the resources found in the Arctic.

- A considerable investment in infrastructure (ocean and land-based) along the Arctic shipping lanes.

- A reduction in insurance, escort costs and more transparency/stability associated with the shipping charges while transiting these routes.

- Overcoming the significant amount of sea ice that is present during the winter months.

Only time will tell if the Northern Sea Route fulfills President Vladimir Putin’s prediction of a shipping lane that rivals the Suez Canal.

These charts show the Northwest Passage (left) and Northern Sea Route (right) compared with currently used shipping routes, Panama and Suez Canals.

Source: Grid Arendal

- Arctic impact outside the Arctic Circle

The occurrence of extreme weather is not a new phenomenon. We have been experiencing such events since the beginning of human evolution. But what would happen if the frequency of flooding, heat waves or severe storms events increased? Could we still cope?

More and more research is suggesting what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic. For example, it appears that the significant reduction in the Arctic sea ice is affecting the position of the jet stream. This in turn may lead to the more frequent occurrence of extreme winter snow conditions (cold air outbreaks) such as those we have witnessed recently in north-east America. In 2014, a US National Climate Assessment report suggested that the continued reduction of sea ice could provide a tipping point whereby the Arctic Ocean becomes a permanent, nearly ice-free state. The repercussions of this will be experienced far beyond the Arctic.

Another elephant in the room, however, is the slowly increasing melt of the Greenland ice sheet. Meltwater from this ice sheet, combined with the Antarctic ice caps and glaciers around the world, have the potential to significantly increase the sea level, triggering a range of disasters, such increased coastal flooding, especially in low-lying coastal countries.

This chart shows the estimated, observed and possible future amounts of global sea-level rise from 1800 to 2100, relative to the year 2000.

Source: Adapted from Parris et al. 2012 with input from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Arctic science relies upon the knowledge and understanding of many global experts, but there’s still a lot that scientists don’t yet know about the Arctic’s future, both environmentally and economically. There is also a lot more we need to know about the socio-economic implications, and what engineering and technological solutions are needed.

Arctic change is at a critical juncture. Politicians and policy-makers, as well as industry leaders and the public, need to have the most up-to-date and robust science available on Arctic change. Holistic, multi-sectorial programmes like the EU-funded ICE-ARC, US-funded SEARCH, Canada-funded ArcticNet, and the Japan-funded ArCS programme, are doing this in conjunction with other, more traditional Arctic programmes from a large number of countries (Belmont Forum.)

The multi-sectorial issues associated with Arctic change transcend national boundaries and a diverse range of stakeholders – governments, indigenous communities, policy-makers, the public, industry and civil society. All want to have a voice in Arctic issues. Despite the growing amount of Arctic science, all nations lack the combination of expertise, knowledge, logistical capability and budget to independently tackle Arctic challenges: a truly international and integrated effort is needed.

Informed decisions on the Arctic must be evidence based and not ideologically driven.

This is part of a four-part series in which we discuss how Arctic summer sea ice affects our global economy, our lifestyles and the Earth’s ecosystem. We also sketch out reasons to be hopeful.

Authors: Dr Jeremy Wilkinson (from British Antarctic Survey, UK), Michael Karcher (from Alfred Wegener Institute, Germany) and Jean Claude Gascard (from Pierre and Marie Curie University, France) are working on the European Union’s Ice, Climate, Economics – Arctic Research on Change project (@ICEARCEU).

Image: A total solar eclipse is seen in Longyearbyen on Svalbard March 20, 2015. REUTERS/Jon Olav Nesvold/NTB scanpix

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Dipali Khandelwal and Hemlata Chauhan

May 19, 2025

André Vasconcelos and Jack Hurd

May 15, 2025

Oscar Castañeda Samayoa

May 15, 2025

Kristian Teleki

May 12, 2025

Jean-Claude Burgelman and Lily Linke

May 9, 2025