How do we resolve Europe’s problem loans?

Stay up to date:

Financial and Monetary Systems

Problem loans are clogging the arteries of Europe’s banking system. The global financial crisis and subsequent recession have left businesses and households in many countries with debts that they cannot repay. Nonperforming loans as a share of total loans in the EU have more than doubled since 2009, reaching €1 trillion—over 9 percent of the region’s GDP—by end-2014. These loans are particularly high in the southern part of the euro area, as well as in several Eastern and Southeastern European countries. Only a handful of countries have managed to lower their non-performing loan ratio to below its post-crisis peak.

Causes

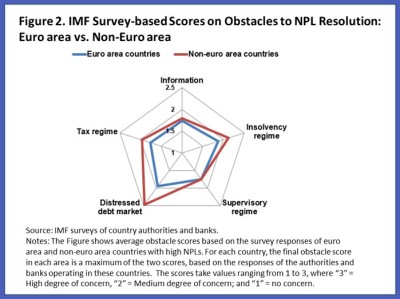

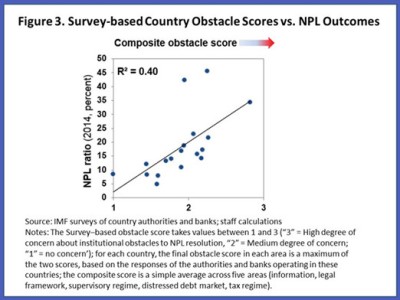

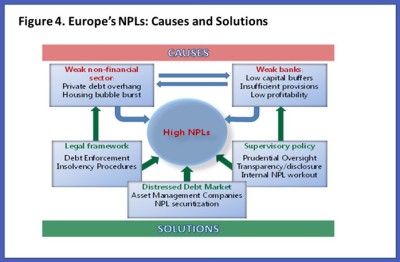

A recent IMF study on the causes and consequences of persistently high nonperforming loans finds that the weak economic recovery is only part of the story and that the underlying reasons are often deep rooted. Notably, European banks are writing off their problem loans much more slowly than American or Japanese banks, despite a much higher stocks. Much of the inertia is due to shortcomings in supervisory and legal frameworks as well as the lack of well-developed distressed debt markets. A new survey of European country authorities and banks shows that deficiencies in the legal framework and underdeveloped distressed debt markets are, on average, seen as the most severe obstacles to resolving nonperforming loans. The challenges are generally even more daunting for countries outside the euro area. And the different obstacles are interlinked, with difficulties in one area compounding challenges in others.

More severe structural obstacles are associated with worse nonperforming loan outcomes. Insufficiently robust supervision can allow banks to avoid dealing with large stockpiles of nonperforming loans and continue carrying them on balance sheets. Accounting rules tend to hinder timely loss recognition and inflate “provisions”—the cash that banks are required to set aside to cover expected losses from bad loans. Weak debt enforcement and ineffective insolvency frameworks lower the recovery values of problem loans. And markets for distressed debt in Europe—with some notable exceptions—are still too small, preventing the entry of much needed capital and expertise.

Consequences

Persistently high nonperforming loans are a drag on economic activity. They tie up bank capital that could otherwise be used to expand lending, lower bank profitability and raise bank funding costs. By holding back lending, they also reduce the effectiveness of the European Central Bank’s monetary policy. Nonperforming loans should either be written off as loans that are beyond recovery, or restructured in a way that gives viable debtors the breathing space they need. This would, in turn, help to advance corporate restructuring, and effectively channel credit to growing firms.

Solutions

Reducing nonperforming faster requires a comprehensive approach. Such a strategy would have three main pillars:

- First, the European Central Bank and national regulators should strengthen bank supervision. International experience shows that swift recognition of loan losses is crucial to repairing bank balance sheets. Banks should be asked to develop comprehensive nonperforming loan plans and meet loan restructuring targets within a reasonable time. They should also be required to set aside more capital for nonperforming loans that remain on their books for too long, and adopt more conservative provisioning and collateral valuation to encourage swift resolution.

- Second, reforms are needed to make bankruptcy regimes more efficient and debts easier to collect. There is currently enormous variation in legal frameworks across countries. For example, the average length of foreclosure proceedings in Italy is almost five years compared to less than one year in Germany and Spain. Shorter court procedures, stronger institutional frameworks and greater use of out-of-court mechanisms would increase collateral recovery values and therefore make it easier for banks to dispose of bad loans. And greater involvement of public creditors in resolving these loans is essential.

- Third, active markets in distressed assets need to be developed. A liquid market can connect banks (sellers) with specialist investors (buyers) experienced in managing impaired assets. Often a publically supported asset management company may be instrumental in jump-starting such a market. Successful examples include the U.S. Resolution and Trust Corporation in the 1980s, those in Asia during the financial crisis and Spain’s SAREB.

This is a challenging reform agenda, but the potential pay-off is high, whereas delaying the resolution of problem loans increases the risk of stagnation.

This article is published in collaboration with IMF Direct. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Shekhar Aiyar is a Deputy Chief in the European Department of the IMF, and Mission Chief for Latvia. Anna Ilyina is currently an Advisor in the European Department (EUR) at the International Monetary Fund, where she heads the Emerging Economies Regional Studies Division.

Image: European Union flags fly outside the European Commission headquarters in Brussels. REUTERS/Thierry Roge.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Aengus Collins

April 15, 2025

Spencer Feingold

April 15, 2025

Andrew Collinge and Katie Adnams

April 11, 2025

John Letzing

April 11, 2025

Michelle You

April 10, 2025

Steve Reis and Jill Zucker

April 10, 2025