How global debt has changed since the financial crisis

Stay up to date:

Global Governance

Debt levels have been a subject of constant news in the years since the financial crisis — from the sub-prime housing crisis in the United States, to the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, to the dramatic increases in debt evident in emerging markets now.

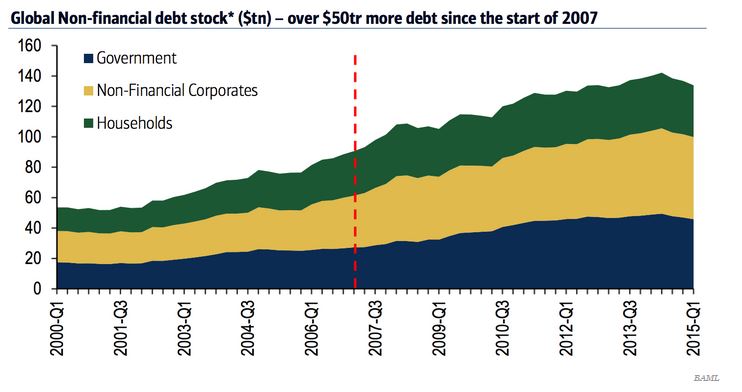

Graphs produced by analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch show an astonishing acceleration in global debt levels, and demonstrate just how little de-leveraging there’s been since the 2008 financial crisis (none). They say its evidence that “the world is still in love with debt.”

After 30 years of relative stability from the early 1950s to the early 1980s, something changed, and debt started ramping up:

BAML

BAML

Debt then took a rapid step up in the mid-1980s, and another in the late 1990s. Over the last 30 years or so, global debt has risen by around 100% of GDP — so it hasn’t just grown in total terms, but has massively outstripped the economic expansion over that period.

In some developed economies, like the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland, there’s been some deleveraging since the financial crisis, particularly by households. But that’s been more than offset by increases in emerging markets.

The total stock of global debt, even excluding debts held by the financial sector, is up by more than $50 trillion. That’s an increase of more than 50%.

Household debt has ticked up a little, and government debt has expanded as states attempted to stimulate their economies in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

But the main increase has been down to non-financial corporate debt, which has risen by 63% over the period, largely in emerging markets. Recent analysis by Australian investment bank Macquarie shows an astonishing leap in debt among Chinese commodity companies over the last 7 years.

Looking at these sort of charts, it’s clear to see why economists like Ken Rogoff are so concerned about global debt levels. In the Financial Times earlier this month, Rogoff argued that a debt hangover is a better explanation of the world’s slow growth than a prolonged demand deficiency, often called secular stagnation. Here’s Rogoff:

Actually, there can be little doubt that a debt super cycle lies behind a significant part of what the world has experienced over the past seven years. This resulted first in the US subprime crisis, then the eurozone periphery crisis, and now the troubles of China and emerging markets.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs recently referred to the challenges currently faced by debt-laden emerging markets as the “third wave” of the financial crisis.

This article is published in collaboration with Business Insider. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Mike Bird is a European markets editor, working from London and covering financial and economic issues.

Image: A man walks past buildings at the central business district of Singapore. REUTERS/Nicky Loh.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Resilience roundtable: How emerging markets can thrive amid geopolitical and geoeconomic uncertainty

World Economic Forum

July 9, 2025

Gayle Markovitz and Beatrice Di Caro

July 9, 2025

Ajay Kumar, Neha Thakur and Siddharth Sharma

July 8, 2025

Rania Al-Mashat

July 7, 2025

Bright Simons

July 7, 2025