How should European economies manage their foreign currency loans?

Stay up to date:

European Union

The recent decision in Poland and Croatia to limit the adverse consequences of Swiss franc denominated loans for households, has put a spotlight on foreign loan hangovers in Central and Eastern Europe. This came after the Swiss national bank’s decision to end the peg to the Euro in January 2015 (Hungary already set steps in November 2014). This blog describes (i) the extent of the foreign exchange borrowing (and the prominent role of the Swiss Franc) and (ii) the respective macro-prudential provisions adopted.

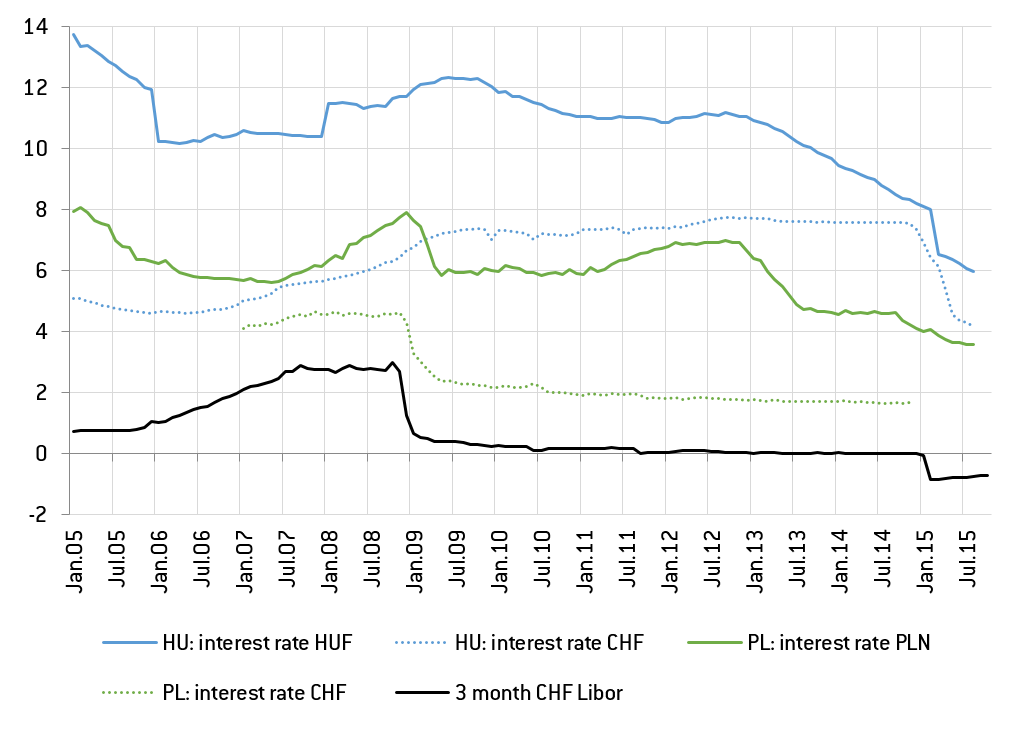

Borrowing in foreign currency increased substantially in the mid-2000s, supported by a carry trade motive, as households (as well as corporations and local authorities) borrowed in lower-yielding foreign currencies to finance the purchase of domestic assets such as housing. As Figure 1 shows, interest rates on mortgage loans in CHF in Hungary amounted to 5.1% in January 2005, less than half the domestic rate of 13.8%. A similar picture can be observed in Poland, but with a somewhat lower spread between domestic and Swiss-franc loan interest rates. The risk of foreign currency loans was perceived as low, even for unhedged customers, as expectations of further currency appreciation supported demand for foreign currency loans in countries with a floating exchange rate regime such as Hungary and Poland.

However, with the start of the financial crisis in 2008/2009, households’ perception of exchange rate risk changed dramatically, as domestic currencies devalued greatly and the Swiss franc appreciated on the back of safe haven inflows. At the same time, interest rates on mortgage loans for households fell in Poland (Figure 1), relieving pressure on foreign and domestic loan owners somewhat . In Hungary, interest rates for domestic loans increased throughout 2009 (peaking at 12.3% in July of the same year), while rates on loans in CHF continued to increase slightly up to beginning of 2013.

Figure 1: Swiss franc and domestic currency mortgage loans rates for households in Hungary and Poland and 3-month CHF LIBOR (%)

Source: National central banks and ThomsonReuters Datastream; Note: interest rates refer to monthly average agreed interest rates on outstanding amounts.

As shown in Figure 2, by end-2009 foreign currency loans in Hungary amounted to 47% of GDP (30.6 % of GDP in CHF) and to 16 % of GDP in Poland (11.6 % of GDP in CHF). In end-2011, Croatia reports foreign currency loans of 67% of GDP (9.6 % of GDP in CHF) in end-2011. Hence, the Swiss franc played a prominent role in Hungary and Poland.

Figure 2: Currency composition of loans to the non-financial sector (% of GDP)

Source: ECB and AMECO; Note: latest data available 2015 Q2, end of year data.

Macro-prudential measures in the context of foreign currency lending

Excessive foreign-currency lending can endanger financial stability; domestic currency depreciation, an increase in foreign interest rates or a deterioration of macroeconomic conditions could put under pressure the debt repayment capacity of unhedged households. This would increase the share of non-performing loans on bank balance sheets and might eventually hit banks’ profits and tighten lending to the real economy. Moreover, ECB research shows that foreign lending makes the job of the central bank harder: on the one hand, restrictive monetary policy leads to a decrease in domestic currency lending, accelerating on the other hand the growth of foreign currency denominated loans. Poland, Hungary and Croatia have set in place macro-prudential tools to deal with the risks stemming from foreign currency lending.

Poland issued ‘Recommendation S’ in 2006, which included the creation of depreciation buffers for banks and the obligation to inform customers of the related risks. In 2007, the risk weight for foreign currency mortgage loans to households was increased. Moreover, to tackle an eventual currency mismatch in bank funding, liquidity limits were introduced in 2007. Further tightening happened in 2010 and 2011, as more stringent tools which targeted borrowers were introduced, limiting debt-to-income ratios for foreign currency-denominated loans to unhedged borrowers, and raising again risks weights.

Given the substantial amount of foreign currency lending in Croatia in the 2000s, it was also one of the most active countries when it comes to macro-prudential policies, introducing among others limits on banks’ funding currency mismatch, an increase in risk weighting, adjustments to reserve requirements and a creation of liquidity buffers linked to foreign currency loans.

Hungary introduced measures starting in 2010, which encompassed lower loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios for foreign currency loans. In 2011, the government adopted repayment schemes, which allowed early repayment of foreign currency mortgages with an artificially strong exchange rate, forcing banks to take massive losses (see ECB opinion). Foreign currency lending was still possible, but only under very tight credit conditions. In February 2015, Hungary’s banks converted most foreign currency loans into Hungarian forints, at the market rates prevailing at that time, based on a decision made in November 2014. Thanks to this the substantial appreciation of the Swiss franc in January 2015 did not have an impact on household mortgage borrowers.

Figure 3: growth rate of foreign-currency and domestic-currency loans to the non-financial sector (year-on-year % change)

Source: ECB; Note: latest data available 2015 Q2.

As Figure 3 shows, before the financial crisis in 2008, Swiss-franc loans grew substantially more than the domestic-currency denominated loans in both Hungary and Poland. With the start of the financial turmoil, growth rates of Swiss-franc denominated loans fell both in Hungary and Poland from around 40% to around zero over 2008. By the end of 2009, growth rates of foreign-currency loans fell below their domestic-currency counterparts in both countries, and stayed below thereafter. By the second quarter of 2015, the share of foreign currency loans decreased in all three countries (Figure 1), and especially in Hungary the share of foreign loans dropped to only 2.5% of GDP after the conversion into Hungarian forints (which explains the sharp drop in Swiss franc loan growth rate, and a sharp rise in domestic loans in Hungary as reported in Figure 3).

This development might reflect on the one hand a drop in supply, due to macro-prudential measures. In this context, ECB research highlights that such measures appear to have been effective in curbing foreign currency lending, but weaken shortly after the policies are implemented. On the other hand, it might reflect a drop in demand, as consumers’ perception of the exchange rate risk changed.

Both governments in Poland and Croatia have put the foreign loan overhang high on the agenda, as elections are around the corner, and policies on how to convert Swiss foreign currency loans are being unveiled (see ECB opinion on the Croatian and Polish law).These policies, more than being macro-prudential, are dealing with the burden-sharing aspect, once the foreign-currency hangover has turned out to be problematic in the aftermath of the Swiss franc appreciation. Looking ahead, macro-prudential policy measures will continue to be key in order to avoid waking up from yet another foreign loan hangover.

This article was originally published by Bruegel, the Brussels-based think tank. Read the article on their website here. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Pia Hüttl is an Austrian citizen and she is an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel.

Image: An employee counts Euro notes. REUTERS/Pichi Chuang.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Atul Kumar

August 12, 2025

Elizabeth Henderson and Daniel Murphy

August 8, 2025

Li Dongsheng

July 31, 2025

Charlotte Edmond

July 30, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi

July 30, 2025

Matt Watters

July 29, 2025