Is Europe in a digital recession?

Bhaskar Chakravorti

Senior Associate Dean, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts UniversityStay up to date:

The Digital Economy

You may have heard that Europe is in a state of crisis. This has nothing to do with an influx of refugees, or Greek debt, or even the future of the European Union. The crisis we speak of has even more severe consequences for Europe’s global competitiveness. In our research on the state and pace of digital evolution worldwide, we have found that the old continent is in the midst of a “digital recession.”

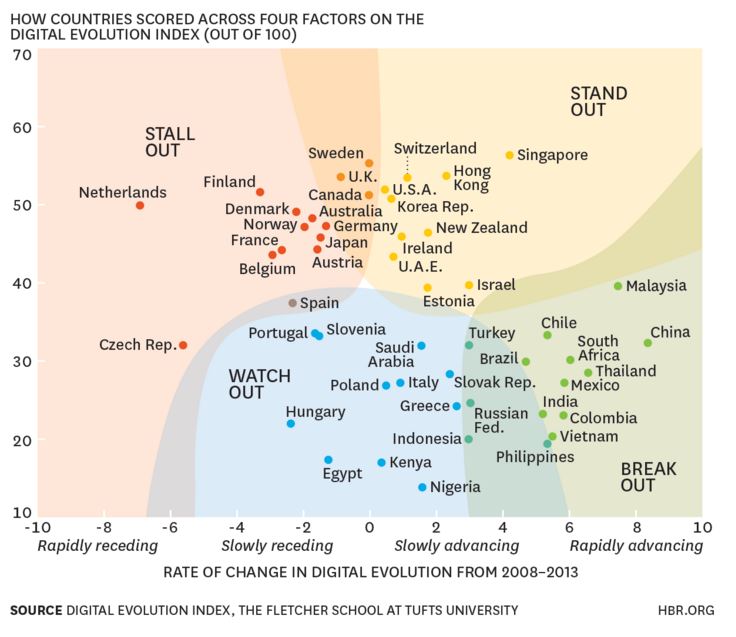

Of the 50 countries we studied in our Digital Evolution Index, 23 were European (not counting Turkey). Of these, only three, Switzerland, Ireland, and Estonia, made it to a commendable “Stand Out” category – which means that their high levels of digital development are attractive to global businesses and investors and that their digital ecosystems are positioned to nurture start ups and internet businesses that can compete globally.

Fifteen European countries have been losing momentum since 2008 in terms of their state of digital evolution – this is what we mean by a digital recession – with the Netherlands coming in dead last in our momentum rankings. European countries occupy the nine bottom spots in our list of 50. Plus, the digitally receding countries include large economies like Germany, the UK, and France, as well as Finland and Sweden, Scandinavian tech powerhouses that were the early leaders of mobile telephony. Across the rest of Europe, the state of digital evolution has been mediocre and the pace of improvement, tepid.

This dismal performance points to a glaring – and growing — digital gap as Europeans watch the U.S. and China take the lead in tech innovation. President Obama said it plainly in a recent interview: “We have owned the Internet. Our companies have created it, expanded it, perfected it in ways that they can’t compete,” referring to the Europeans. And a recently released report suggests that Europe’s digital divide problem extends way beyond the Atlantic; Europe is a distant third behind North America and Asia for $100 million plus financing for VC backed companies.

How has Europe dealt with the situation? The response has primarily taken three forms: One has been that of frustration with — and even rejection and censure of — the more dominant U.S. position. Deutsche Telekom’s launch of E-mail Made in Germany promised all data will being kept out of the U.S. government’s prying eyes. At the street level, in France particularly, there is anger against what French critics call Les Gafa (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon).

At the regulatory and policy levels, authorities have doggedly pursued U.S. tech companies. The EU’s antitrust regulator charged Google for abuse of its position as the dominant search engine to promote its own businesses, while the European Parliament even voted in favor of breaking up Google . And, European officials have lodged a plethora of complaints extending well beyond anti-trust concerns, such as tax avoidance and privacy concerns. EU citizens now have the right to “be forgotten” by petitioning Google to delete certain search results, while regulators in the Netherlands, Spain, among others, are investigating Facebook’s privacy practices.

Another response has been an acknowledgement by the President of the European Commission (EC), Jean-Claude Juncker, of Europe’s severe digital decline. The EC’s pronouncements signal the beginnings of a “Digital Maastricht Treaty.” The proposal is to create a “Digital Single Market” in the EU. The goal of the Digital Single Market is an ambitious one: to deliver by the end of 2016 the equivalent of US$ 471 billion per year to the regional economy and 3.8 million jobs.

There are subtle, yet significant, changes happening already. In Paris, an endeavor to reclaim the word “entrepreneur,” has seen the city open its doors to attract foreign talent with a recently launched tech visa aimed at encouraging foreigners to incubate startups on the city’s eastern edge. Startup clusters are also emerging in London, Stockholm, Berlin, and Helsinki.

But there are still barriers to be overcome before Europe’s digital potential can be realized. Based on our research, we propose four critical areas of focus:

Harmonizing across the e-commerce value chain. Paradoxically, it is easier for people to cross borders within the EU than it is for digital goods and content to do so. Telecommunications, marketplace platforms, payment services, and postal and logistics systems are balkanized. While 44% of EU residents shopped online in 2014, a paltry 15% bought from another member state; barely up by six and a half percentage points since 2010, according to the European Commission’s (EC) “Digital Agenda Scoreboard 2015.” According to Der Standard, an Austrian newspaper, mailing a parcel from Munich to Salzburg (distance: 145km; 90 miles) costs many times more than mailing it from Munich to Berlin (distance: 585km; 364 miles). There’s also the matter of language complexity — for small and medium enterprises, creating a web storefront and customer support in the plethora of European languages can be prohibitively expensive.

If things look bad for goods moving across borders electronically, they look even worse for transporting content. There are a staggering 250 collective management organizations overseeing digital content, according to a 2014 EC press release. Transparency and governance issues abound. In some cases, competing organizations represent the same category of rights-holders; in some others, national monopolies dominate.

The first step in unclogging these bottlenecks and unlocking the digital potential of the union is for the regulators to move away from reflexive responses to competitive winds from across the Atlantic to a more reflective approach — creating uniform standards, better processes, and streamlining of digital rights management to harmonize hundreds of byzantine regulations across EU. This would be a laborious — but achievable — task for the EC and national regulators in the next few years.

By many measures, the UK is ahead of the others in terms of its digital foundations and sophistication; for example, the proportion of retail in the U.K. penetrated by B2C e-commerce is nearly twice the European average and higher than even in the U.S. The EC would also do well to harness intra-European rivalries that go back centuries, lately relegated to little else than the UEFA League, to get member states to compete with one another and inspire the laggards to catch up with their better peers. According to estimates by McKinsey, if France were to shift into a higher gear and equal the U.K.’s digital state, its total economic gain could be to the tune of Eur 100 billion.

Investing in innovation capacity. To the extent that inputs – such as R&D expenditures – are a proxy for innovation capacity, Europe, according to a June 2015 report by McKinsey Global Institute, spends 2% of its GDP on R&D, about the same as China’s 1.98%, but well behind United States’ 2.8%. More significantly, Europe’s private sector R&D spending at 1.3% of GDP, compares poorly with that of the U.S. (1.8%), Japan (2.6%), and South Korea (2.7%). Europe’s gap is concentrated heavily in electronics, software, and internet services. In their tracking of “unicorns,” or venture-backed companies valued at $1 billion or more, the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones VetureSource find that as of July 2015, a mere 8% are Europe-based, compared to 25% from Asia, and 67% from the United States.

A major reason for this deficit is insufficient investment. Traditionally, Europe’s growth has been financed to a significant extent by the banking sector, and there has historically been a continent-wide leeriness towards the provision of risk capital by other financial types. Venture funding for European digital groups in 2014 remained a fifth ($7.75 billion) of that of the United States ($ 37.9 billion). Another area where the absence of a vibrant VC and corporate investment culture hurts promising startups in Europe is that, because realizing gains from an IPO on European exchanges is still difficult, a primary exit for entrepreneurs is to sell to U.S.-based corporations – prominent examples being Skype, founded in Estonia, acquired by eBay in 2005 for $2.6 billion, and Swedish Mojang AB, the maker of the “Minecraft” video game, acquired by Microsoft for $ 2.5 billion in 2014.

What Europe needs is a self-reinforcing cycle to kick in with a critical mass of VC-backed companies that have demonstrated some measure of scaling-up and success in growing valuations and promising exit options – crucial to attracting more investments in the tech sector.

Developing a risk-tolerant culture. The essence of Silicon Valley – among its other supporting attributes — is a culture and an ecosystem that engenders a willingness to take risks and fail. Even Asia – particularly in China and India – such cultural shifts are visible; Europe still frowns on failure. According to a study from Youth Business International and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, those aged 18-35 in the EU were much more likely than anywhere else in the world to be deterred from entrepreneurship by a fear of failure. More than 40% in Europe cited fear of failure as a barrier, compared to just 24.0% in Sub-Saharan Africa and 27.7% in Latin America.

Changing attitudes toward failure requires cultural shifts. Some of the best places for such changes to take root are in the cities that become technology hubs: Berlin, London, Barcelona are examples. Even Tel Aviv (though technically not in Europe, but with strong linkages to the continent) can act as such a hub, given its thriving start-up culture. Universities also play a central role. Several European schools have facilitated such startup ecosystems; some notable examples include: the Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh; Chalmers University in Goteborg, Sweden; the universities of Twente, Groningen, and Leiden; the Federal Institutes of Technology in Zürich and Lausanne; and in the U.K., Oxford and Cambridge.

Reforming immigration policies. Europe is experiencing an entirely separate crisis in dealing with the influx of illegal immigrants and political refugees. Even legal immigration can be a contentious political issue, especially when unemployment rates among those with tertiary education in countries such as Greece, Spain, and Portugal are high, and rising. The recent rise of the anti-immigrant hard-right parties in countries such as Denmark and Finland makes it harder for a pro-growth immigration policy to take root region-wide. It’s role in welcoming Syrian refugees notwithstanding, Germany’s policies towards highly skilled immigrants from outside the EU remain ambivalent, at best. Its proposal to bring in information technology workers from India, prompted the Christian Democrats to campaign on the slogan Kinder statt Inder, “children not Indians.”

The continent is aging, and pro-growth immigration can help replenish the youth and entrepreneurial talent pipelines. According to a McKinsey report, if Europe boosted its immigration from outside Europe, from 2.6 people per 1,000 inhabitants per year to 4.9 people, it could compensate for its projected 11 million drop in working-age population in 2025. Also, there is evidence from across the Atlantic that immigration spurs entrepreneurship, particularly in the digital industries: According to The Economist, over 40% of Fortune 500 firms in the United States were founded by immigrants or their offspring; while the foreign-born constitute barely an eighth of America’s population, a quarter of technology startups have an immigrant founder. Engine, a startup advocacy, completes the picture with its assessment that 4.3 new jobs emerge in the local economy over time for every job created in the high-tech sector; more than three times the local multiplier for manufacturing jobs.

It is time Europe took notice of the silent – and ultimately fundamental — crisis that lurks within it. Europe’s leaders and entrepreneurs need to wake up to the digital recession on the continent and put a new strategy into place.

This article is published in collaboration with Harvard Business Review. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Bhaskar Chakravorti is the Senior Associate Dean of International Business & Finance at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. Ravi Shankar Chaturvedi is Research Fellow at Fletcher’s Institute for Business in the Global Context at Tufts University.

Image: An illustration picture shows a projection of binary code on a man holding a laptop computer. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025