The future of Eurasia’s competitiveness

Stay up to date:

Competitiveness Framework

Some of the Eurasian economies have improved their ranking in this year’s Global Competitiveness Index: the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan climbing eight places, and Tajikistan gaining 11.

While improvements in some aspects of competitiveness have been achieved, a more detailed analysis of the the results – combined with the latest developments in the global economic outlook – finds that the region’s future competitiveness may still be at risk.

After having grown significantly in the past, Eurasian countries’ future growth is forecasted to remain below 4%, which falls short of the performance needed to attain sustained prosperity.

Ukraine and the Russian Federation have already entered into recessions, which might have a significant impact on other economies in the region. In addition, low oil prices and low demand are likely to reduce public finances and the resources available for competitiveness-enhancing policies in these countries and across Eurasia.

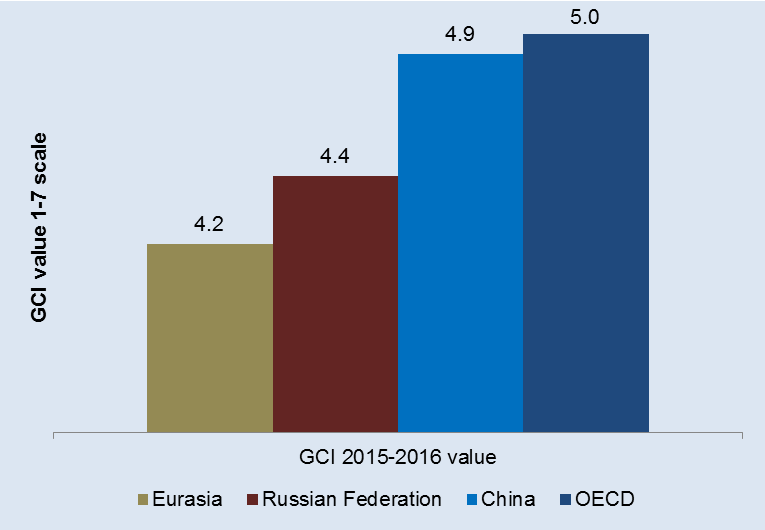

These trends are partially reflected in the performances of these economies in the Global Competitiveness Index. Despite some improvements, most Eurasian economies struggle to converge towards the higher standards of competitiveness that are key to achieving a more sustainable growth path and higher standards of living. The competitiveness performance of economies in this region still lags significantly behind OECD economies and countries that have achieved growth by transforming the structure of their economy.

Performance in the Global Competitiveness Index 2015-2016

Source: Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016

The Russian Federation, for example, has managed to improve its ranking this year, but only thanks to a lag in statistics that do not yet fully take into account the impact of lower oil prices on its macroeconomic environment, geopolitical tensions and some technical statistical adjustments. Russia has certainly made significant efforts to improve its goods market efficiency by slashing the amount of time and procedures required to start a business (as reflected by World Bank data) and has also improved its business environment. However, it has not yet tackled its longstanding structural hurdles, such as institutional and financial fragilities, limited market competition and innovation capacity.

Other economies in the region, after taking advantage of high commodity prices, have not been able to sustain growth beyond changes in the global economic reality following the global financial crisis. For example, between the year 2000 and the beginning of the crisis in 2008, Kazakhstan grew almost 10% a year and Azerbaijan more than 15%, but neither has replicated this performance since. These countries and others in the region (instead of improving the sophistication and diversification of their economies) have become more dependent on mineral exports, exposing themselves to the fluctuations of commodity prices. In spite of the programmes put in place to advance this agenda, little progress has been achieved so far in the region.

In order to achieve higher competitiveness, Eurasian economies need to overcome structural obstacles and pave the way for the development of a stronger and more diversified business sector. Feeble public institutions, lack of strong markets with limited competition and weak regulation of the financial sector remain the main bottlenecks preventing the success of diversification policies.

For example, in terms of intensity of local competition, Kazakhstan is assessed as 94th, Kyrgyz Republic is 115th, while the regional best performer (Russian Federation) only comes 77th out of 140 economies.

Similarly, the financial sector remains very fragile, with the Russian Federation ranking 115th, Azerbaijan 103rd and Ukraine in last position (140th) in terms of soundness of banks.

Lack of transparency also remains a significant problem in several Eurasian economies: business leaders of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russian Federation and Ukraine cite corruption as the most problematic factor for doing business.

In light of these insights, and of the broader regional economic context, Eurasian economies need to address their longstanding institutional and structural fragilities, if they are to return to strong growth and attain a more sustained and shared prosperity.

Read the Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016 here.

Author: Roberto Crotti, Economist, Global Competitiveness and Risks, World Economic Forum

Image: An aerial view shows the capital Moscow, September 17, 2014. REUTERS/Maxim Zmeyev

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025