Three ways to help the Middle East’s refugees

Stay up to date:

Middle East and North Africa

As hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Muslim, seek refuge from war in Iraq and Syria, many now call this moment a “migrant crisis.” Of course, migrants don’t leave bombed out homes, tortured relatives, and genocide: refugees do. And for them, the crisis is what they left, not their arrival.

If we are to fairly address the deep human needs brought on by the war in Iraq and Syria, then we must acknowledge the world as it is, to include the faith factor in various dimensions. Religion plays a key role, from the beliefs and norms of the societies absorbing new arrivals to the values and needs of refugees; and from the security concerns of those unable to flee (especially religious minorities) to harnessing the faith communities around the world who are eager to respond.

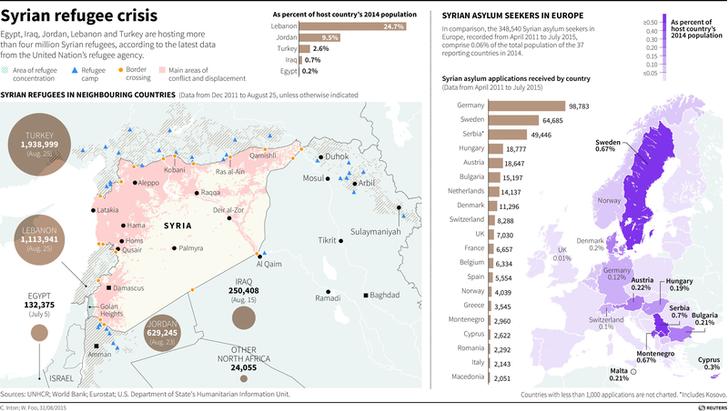

Source: Reuters

Three options exist. There is the evacuation of refugees and the process by which they emigrate to Europe and North America, which deserve careful consideration. But these options only deal with symptoms. At some point, the root cause must be addressed. If it is not, then there will only be more refugees. And so, even greater attention must be given to enabling those at risk in Iraq and Syria to live in safety, so that they do not become refugees in the first place.

1. Evacuate them to safety. Various efforts are now underway to quickly remove (e.g., airlift) those most at risk, especially religious minorities. For example, the United Kingdom’s Lord Weidenfeld—a Jew who survived the Holocaust because of Christians—has set up a fund to rescue Christians, providing them with 12-18 months of financial support while they get used to their new home.

Donors should always follow their hearts as they discern whom to help. How the help is administered, however, is critical if it is not to contribute to greater problems. It is immensely difficult to decide who to help and who not to. How is the selection made?

And what happens once people are evacuated? Are families and villages kept together? Is there an “acclimatization and after-care” process, once families arrive in a new place? If we seek to sustain the unique contributions of these ancient communities, we need to understand what it is we are saving—including their faith. Donors need to work with institutions capable of addressing these complexities.

But we also have to understand the implications for those left behind. How does the departure of the few who happen to be chosen impact the majority of those who are left behind? How, for example, might ISIS use the evacuation for its own purpose, as it celebrates the completion of its religious cleansing? As I have suggested elsewhere, there are strong arguments that we should make every attempt to keep religious minorities safe in the Middle East.

2. Allow them to emigrate to Europe and North America: For those fleeing by foot or sea, there is an opportunity for Europe and North America to welcome these refugees, the overwhelming majority of whom are Muslims. Three issues, however, loom large. First is the issue of how Europe and North America understand themselves vis-à-vis Islam. Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel—a pastor’s daughter and former East German—was quoted saying the following to Eastern European leaders (behind closed doors on 7 October 2015):

When someone says: ‘This is not my Europe, I won’t accept Muslims’ … I have to say, this is not negotiable,” Politico quoted her as saying. “Who are we to defend Christians around the world if we say we won’t accept a Muslim or a mosque in our country? That won’t do.

Chancellor Merkel is exactly right. How Europe handles the arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees is first about Europe’s own beliefs and convictions. But it is also true that Chancellor Merkel said on 16 October 2010, regarding immigration and Islam: “This [multicultural] approach has failed, utterly failed.”

Which begs the second issue: will Europe (and North America) celebrate the ethno-religious identity of the refugees? Or will Europe and North America merely tolerate the ethnic-religious identity of refugees, expecting them to assimilate, i.e., think and act fully as the majority culture? And what will the refugees want? Will they take on the responsibility of citizenship, living in mutual respect of their neighbors and the rule of law? Or will they self-segregate?

The third issue, then, is to consider anew the policies and processes that help refugees to settle.

Faith communities—at the national and local level—can have an enormous influence in this discussion. At their best, faith communities will welcome the stranger, working to integrate refugees into their homes and communities. Meanwhile, refugees should be guaranteed the right of return to their homes and lands.

3. Enable them to stay in the region in safety: No matter how one considers the above two options, they remain symptoms of the root problem: 1) There will continue to be refugees as long as the geo-political situation is not addressed in Iraq and Syria; and, 2) the overwhelming majority of people will never have an option to evacuate or emigrate. Therefore the question becomes how best to enable refugees of all faiths and none to stay in the region. Here again, faith communities can play an essential role.

In the efforts of my own faith-based institution, we have raised over $3 million from 1,200 donors in the last year as we work with local faith-based partners on programs that rescue (e.g., immediate health and shelter needs), restore (e.g., provide trauma counselling and education), and return those who have fled violence and conflict, irrespective of faith or ethnicity.

Amidst the total destruction of trust among the different ethno and/or religious groups in Iraq and Syria, our joint programs build trust—always through such amazing local partners as Assyrian Aid Society, Yazda, Heart of Lebanon and International Orthodox Christian Charities—by bringing people together around a common need. For example we recently launched two trauma initiatives that serve the Christian and Yazidi communities in Northern Iraq.

In the U.S., another faith-based organization, World Vision, is now mobilizing churches across America to enable refugees in the Middle East. Previously, World Vision raised just $2.7 million for Syria in the past four years. But in the past four weeks, World Vision has raised $3 million from 11,200 donors (please see this 8 October 2015 Congressional Hearing, starting at 32: 40). This effort could be an important model for mobilizing faith communities in Europe and North America.

Finally, despite our best efforts to support refugees who have fled within the region, it only makes sense that they would return to their homes if they felt safe and protected. Given the geo-political complexities—not least the religious and realpolitik rivalry between Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia, the future boundaries of Iraq and Syria, and the role of ISIS and Russia—that possibility seems dim. In my next post, I will discuss the case for a regional safe haven for people of faith who have fled ISIS.

Author: Chris Seiple, Ph.D., chairs the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on the Role of Faith. He is President Emeritus and Chairman of the Board at the Institute for Global Engagement.

Image: Migrants walk on a dirt road after crossing the Macedonian-Greek border near Gevgelija, Macedonia, September 6, 2015. REUTERS/Stoyan Nenov

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Civil SocietySee all

Annette Mosman

June 19, 2025

Laura Henderson

June 4, 2025

Daniel Dobrygowski and Giannis Moschos

May 21, 2025

Gustavo Maia

April 22, 2025

Michael Boampong and Kajsa Hallberg Adu

April 16, 2025

Toshihiro (Toshi) Nakamura and Ewa Wojkowska

April 11, 2025