Which sectors have increased exposure to exchange rate fluctuations?

Stay up to date:

Financial and Monetary Systems

Debt held by firms in emerging market economies in a currency other than their own poses extra complications these days. When the U.S. Fed does eventually raise interest rates, the accompanying further strengthening of the U.S. dollar will mean an emerging market’s own currency will depreciate against the higher value of the U.S. dollar, and would make it increasingly difficult for firms to service their foreign currency-denominated debts if they have not been properly hedged.

In the latest Global Financial Stability Report, we find that firms in emerging markets that have increased their debt-to-assets ratios have generally also increased their overall sensitivity to changes in the exchange rate—commonly called exchange-rate exposure.

We measure this by estimating firms’ exposure indirectly, based on the reaction of their stock returns to changes in the exchange rate. This estimate of foreign exchange exposure in principle accounts for financial hedges, such as swaps, and natural hedges, such as export-oriented firms’ receipts in a currency other than their own, as well as local market conditions. We estimated these foreign-exchange exposures using data from thousands of individual publicly-listed firms. Estimating these exposures is advantageous because firm-level data on foreign currency holdings are generally unavailable.

Bonds do not tell the whole story

Various observers have pointed to the rise in foreign currency-denominated bond issuance by many emerging markets. Various papers, including this one, have documented the rise in emerging market bond issuance in foreign-currency denominations; however, focusing on bonds is not enough to obtain a good picture of firms’ overall foreign exchange exposures.

- First, bank lending remains the most important source of financing for many firms, accounting for over 80 percent of corporate debt.

- Second, firms may hedge currency risk using financial instruments such as swaps.

- Third, overall foreign-currency exposure depends on other factors, such as the composition of firms’ balance sheets, including their assets, and the nature of their business operations. For example, export-oriented firms’ receipts in a currency other than their own, typically the U.S. dollar, can serve as “natural” hedges against their debt obligations in foreign currencies, whereas firms importing inputs from abroad are naturally exposed to the risk of local currency depreciation.

Beg to differ

Our estimated foreign exchange exposures highlight differences across sectors. For example, firms in nontradable sectors, such as construction, tend to have positive foreign exchange exposures – that is, local currency depreciation affects them adversely. This reflects the fact that sectors like real estate tend to do well during periods of capital inflows and currency appreciations (Chart 1). In contrast, export-oriented firms, such as those in the mining sector, tend to have negative foreign exchange exposures, because they benefit from a depreciation of the local currency.

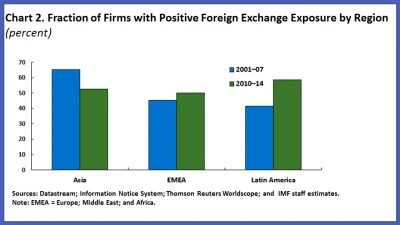

The evolution of foreign exchange exposures after the global financial crisis also differs across regions (Chart 2). For instance, foreign currency exposures appear to have risen the most in Latin America, on average, after the crisis.

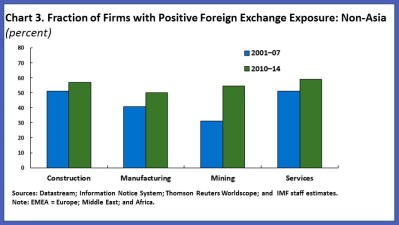

Furthermore, outside of Asia—Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America—the fraction of firms with positive foreign exchange exposures increased across all sectors from 2010 to 2014 (Chart 3).

We then compare the change in foreign currency exposures with the change in the debt-to-assets ratio for listed firms.

Interestingly, the construction sector, where this ratio grew rapidly, is among the sectors perceived by stock markets as having strongly increased its exposure to exchange rate fluctuations since the crisis. These findings suggest that emerging markets must prepare for the implications of a continued appreciation of the U.S. dollar as the U.S. Fed begins to normalize monetary policy.

This article is published in collaboration with IMF Direct. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Selim Elekdag is the Deputy Division Chief of the Global Financial Stability Division at the IMF. Gaston Gelos is the Chief of the Global Financial Stability Division at the IMF.

Image: An employee counts Indian rupee currency notes. REUTERS/Adnan Abidi.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Kaiser Kuo

June 19, 2025

Mamta Murthi and Sania Nishtar

June 19, 2025

Julia Hakspiel

June 17, 2025

Swapan Mehra and Akim Daouda

June 16, 2025

Aengus Collins

June 12, 2025

John Letzing

June 11, 2025