19 charts that explain India’s economic challenge

Stay up to date:

The Digital Economy

India has come a long way in modernizing its economy, reducing poverty and improving living standards for a large segment of its population.

Its economy has been one of the largest contributors to global growth over the last decade, accounting for about 10% of the world’s increase in economic activity since 2005, while GDP per capita in PPP (purchasing power parity) terms is today three times as high as in 2000.

Yet, this period also witnessed a rise in inequality, which has been mainly driven by income gaps between India’s states, and a growing urban-rural divide. India continues to have the largest number of poor in the world (approximately 300 million are in extreme poverty), and nearly half of the poor are concentrated in five states.

Growth has slowed in recent years and several challenges remain unsolved. Bringing more people into the process of generating growth and sharing the gains more widely will make India more resilient for the future.

With one of the largest and youngest populations in the world, India needs to create millions of good-quality jobs in the near future to ensure decent living conditions for the vast majority of its citizens.

With one of the largest and youngest populations in the world, India needs to create millions of good-quality jobs in the near future to ensure decent living conditions for the vast majority of its citizens.

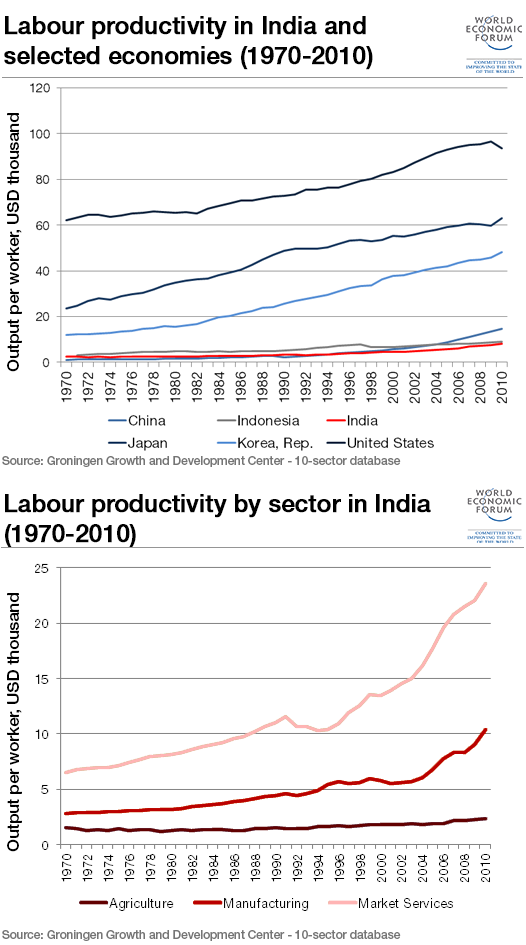

The country is often cited as an example of an economy that is modernizing by jumping directly into services without passing through manufacturing. The weight of manufacturing in India has been relatively stable over the past two decades, at much lower levels than China and ASEAN countries. Business services – a high value added sector – represent a larger share of economic activity in India than in Europe.

Will India be able to achieve shared prosperity without a growing manufacturing sector? Agriculture accounts today for only 16% of total value added (down from 44% in 1965), but still employs about half of the Indian population. Productivity in this sector did not increase significantly in the past decades, limiting improvements in living standards in rural areas.

The competitiveness landscape

After five years of decline, India’s competitiveness improved notably this year as measured by the Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016, where the country improves 16 ranks to 55th of 140 economies.

This improvement can be largely attributed to two main factors.

Firstly, macroeconomic conditions improved significantly. Inflation eased to 6% in 2014, down from near double-digit levels the previous year. The government budget deficit has gradually dropped since its 2008 peak, although it still amounted to 7% of GDP in 2014, one of the world’s highest.

Secondly, the country benefits from the momentum initiated by the election of Narendra Modi, whose pro-business, pro-growth, and anti-corruption stance has improved the business community’s sentiment toward the government. Infrastructure has also improved, but remains a major growth bottleneck. The fact that the most notable improvements are in the basic drivers of competitiveness bodes well for the future, but other areas also deserve attention, including technological readiness.

How inclusive is growth?

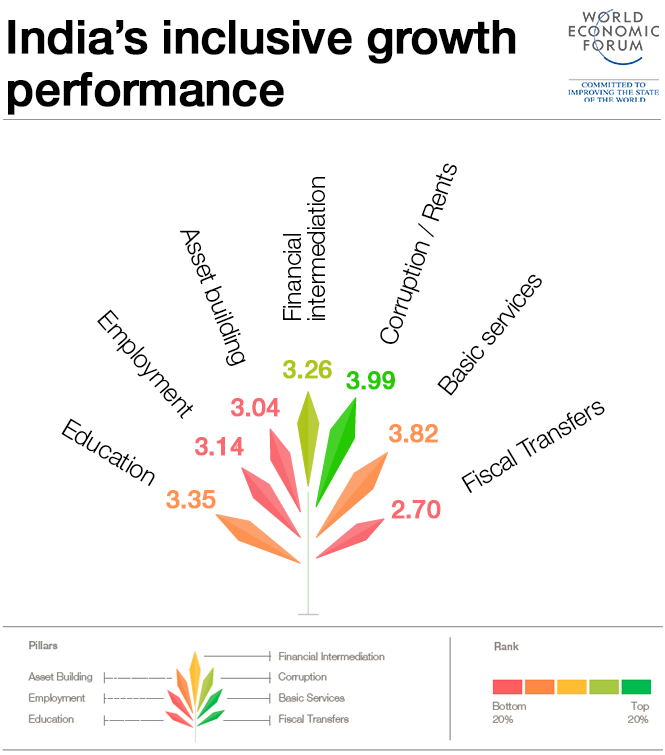

Despite India’s relatively strong record in terms of economic growth over the last decade, its middle class remains small and getting a job is no guarantee of escaping poverty.

India must take further action to ensure that the growth process is broad-based in order to reduce the share of the population living on less than $2 a day—many of whom are employed in informal and low skilled jobs. Educational enrollment rates are relatively low across all levels, and quality varies greatly, leading to notable differences in educational performance among students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

The gender gaps in labour force participation and wages are both high, showing that India’s women are not benefiting equally from economic opportunities. India scores well in terms of access to finance for business development and real economy investment (investment channelled towards productive uses), yet new business creation continues to be held back by administrative burdens. India also under-exploits the use of fiscal transfers compared to peer countries.

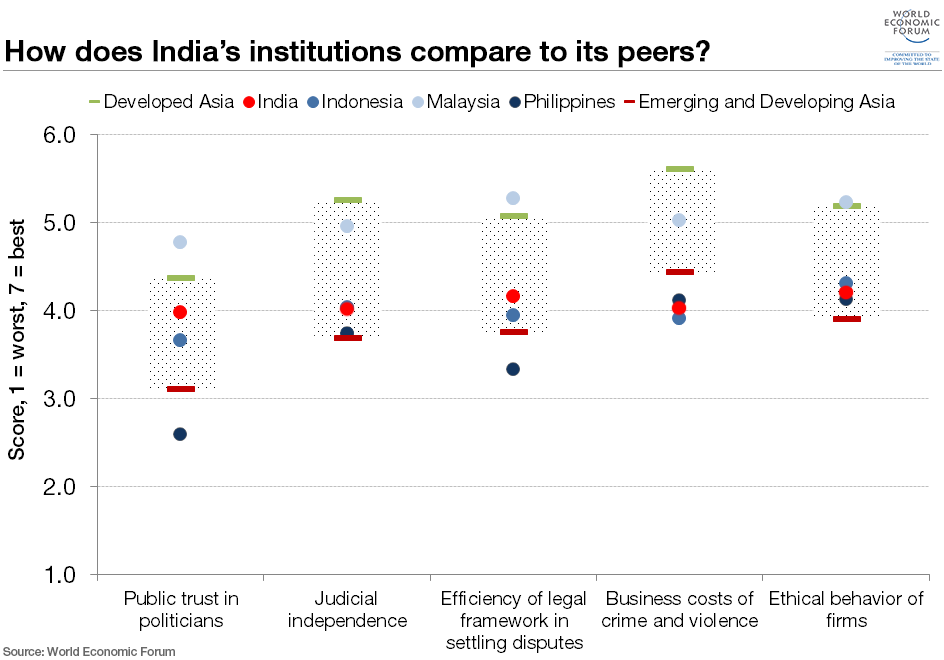

Modernizing India’s public institutions

Modernizing public institutions has been high on the agenda of reforms in India in recent years, and results are starting to show. In 2015, businesses perceived lower levels of corruption among public officials and showed more trust in government’s decisions. Improved public institutions are one of the main drivers of the increase in India’s competitiveness. Yet, there is still a lot of ground to cover.

Private investment, especially from foreign firms, requires a favourable business environment, which includes strong property rights protection and also fair and speedy trials in the case of disputes. To this end, ensuring the independence of the judicial system and increasing efficiency in settling disputes will be key. Business ethics should also improve in line with that of public institutions. Reporting and accounting standards are necessary to ensure transparency in the private sector, increase trust and facilitate long-term financing and investment.

Private investment, especially from foreign firms, requires a favourable business environment, which includes strong property rights protection and also fair and speedy trials in the case of disputes. To this end, ensuring the independence of the judicial system and increasing efficiency in settling disputes will be key. Business ethics should also improve in line with that of public institutions. Reporting and accounting standards are necessary to ensure transparency in the private sector, increase trust and facilitate long-term financing and investment.

Talent, education and social mobility

Educational enrolment rates are relatively low across all levels: barely above the median for its peer group on pre-primary and primary, and below the median for secondary, vocational and tertiary levels.

Only 1.4% of secondary students are enrolled in technical and vocational programs, limiting the talent pool for skilled labor. The average level of education is only 7.3 years and a gender gap continues to persist, with boys benefiting from two more years of schooling than girls. India ranks 31st out of 37 lower middle income countries in providing equal educational opportunities for men and women, which translates into low levels of female participation in the labor force.

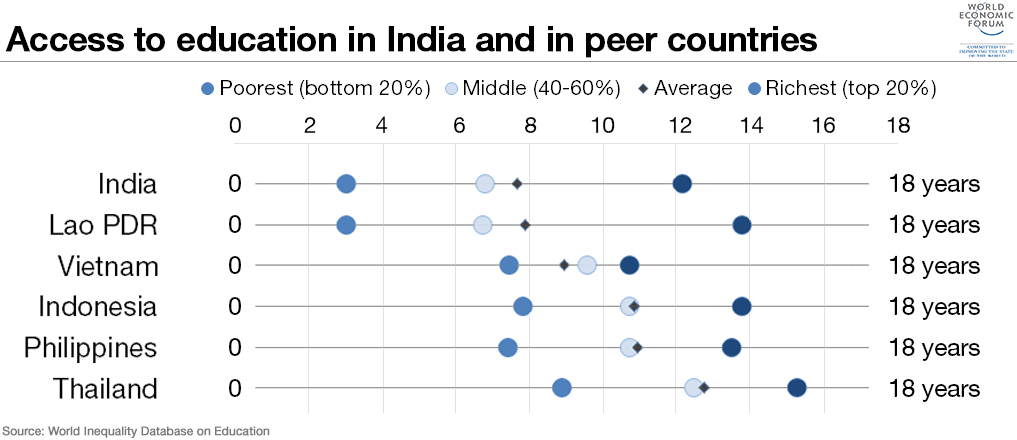

The gap in educational attainment between children from the top and bottom quintiles in India is 8.7 years, with those in the bottom quintile receiving only 2.8 years of education on average and those in the top income quintile receiving 11.56 years. The disparities in educational attainment by income are greater in India than in most other countries with similar income levels, and can be important in transmitting inequality down the generations. The gap is much smaller in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines and larger only in Laos. Thailand stands out for having the best educational outcomes in this peer group on average (nearly 5 more years than India).

The gap in educational attainment between children from the top and bottom quintiles in India is 8.7 years, with those in the bottom quintile receiving only 2.8 years of education on average and those in the top income quintile receiving 11.56 years. The disparities in educational attainment by income are greater in India than in most other countries with similar income levels, and can be important in transmitting inequality down the generations. The gap is much smaller in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines and larger only in Laos. Thailand stands out for having the best educational outcomes in this peer group on average (nearly 5 more years than India).

Unequal access to finance

India scores relatively well in terms of access to finance for developing businesses and investing in the economy. India’s entrepreneurs have better access to bank accounts, credit, venture capital, and equity markets than their counterparts in most peer countries. However, access to finance remains limited for low income individuals, especially women. 400 million people remain unbanked in India and disconnected from the financial system despite impressive gains in recent years. Most unbanked are poor and female: only 27% of individuals in bottom quintiles and 37% of women have access to a bank account. Finance can help poor households optimize severely constrained resources across their lifetime.

Barriers to Entrepreneurship

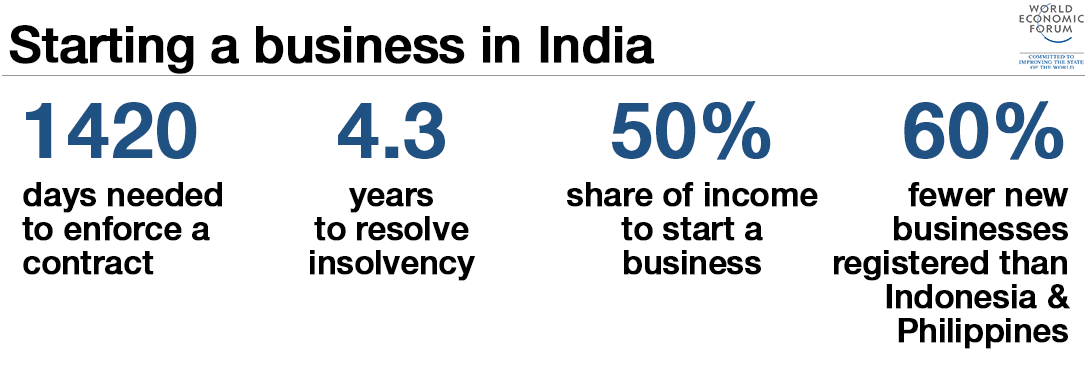

Yet, only 7% used their savings account to start a business (the proportion is even smaller for those in the bottom 40% of the income distribution). A last-placed ranking on small business ownership is evidently not for want of good ideas, as India scores fourth on a measure of patent applications. But budding entrepreneurs are held back by red tape and an inefficient justice system, with relatively low rankings for indicators such as the time and cost of starting a business, enforcing a contract and resolving insolvency.

Closing the infrastructure gap in India

Infrastructure development has not keep up with the increasing needs of the economy. Since 2007, the country slipped 14 ranks to 81st worldwide in terms of overall quality of infrastructure. In a recent report, the World Bank estimates that India might need up to 1.7 trillion dollars to close its gap in infrastructure development. Such a huge challenge cannot be borne by the government alone and will require more private investments and public-private partnerships. Private infrastructure financing totalled only 2.4 % of GDP per year on average from 2009-2013.

A quarter of Indians still do not have access to electricity and almost a third of the urban population live in slums. 65% of the population does not have access to improved sanitation and access remains unevenly distributed. This is also the case for clean drinking water.

Modernizing transport infrastructure will be particularly important to increasing India’s competitiveness. The airline sector is one of the weaknesses of India’s transport system. Operational airports are still out of reach for large parts of the country given that only half of Indian roads are paved, contributing to one of the highest accident rates in the world. On the flipside, the railway system performs relatively better than other modes of transport, traversing the country for approximately 65,000 kilometers (the fourth largest in the world). Nonetheless, investments are needed to improve the speed and efficiency of the system, especially within urban areas.

Connecting India

Despite many clusters of excellence in the IT industry and a vibrant service sector, India is not fully leveraging ICTs (information and communication technologies) for the benefits of its entire population. Regulation of the ICT sector is among the most competitive in the world and costs are low by international standards. Yet, the uptake of ICTs in India remains very low. Fewer than one in five Indians access the Internet on a regular basis, with only 1 percent of the population having fixed broadband (more worryingly, this figure has not gone up significantly in recent years). Smartphones are the privilege of the very few, with 5 mobile broadband subscriptions for every 100 population, while less than two in five Indians are estimated to own even a basic cell phone.

India has been slipping behind other countries in developing Asia over the last decade. Until 2007, internet usage was in line with the median performance of other economies in the region. Since then, countries such as Thailand and the Philippines have experienced a tremendous increase in the uptake of ICTs. Connecting India will mean investing in both physical and human capital to bridge the gap with other emerging markets. ICT could help fulfil India’s ambition to become a global manufacturing hub. Furthermore, ICT could do wonders in improving productivity in agriculture and the services sector, while boosting access to some basic services among the rural population.

India’s tax tystem and social safety net

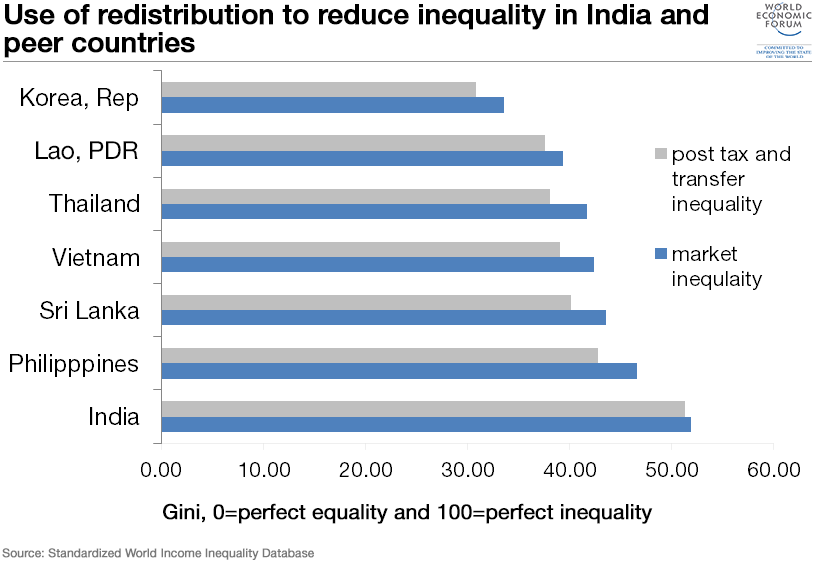

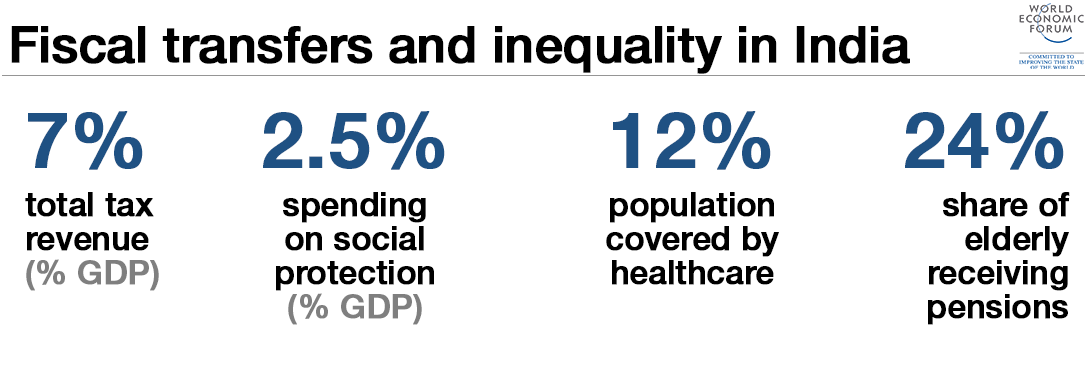

Some countries effectively use redistribution to reduce inequality, but India is not among them. Its Gini coefficient (a measure of income distribution) is the second highest among lower middle income countries and is barely changed by fiscal transfers. Tax revenues are extremely low and India’s tax code is regressive, meaning that the poor bear a heavier burden than the rich, which is not offset by social spending. The country spends only 2.5% of GDP on social protection compared with over 6% in many peer countries.

India has a great deal of opportunity to enhance the generosity and progressivity of its social protection system so that it can give its citizens the safety net needed to take risks and participate fully in the economy and society.

Increasing its narrow tax base can also give India more fiscal space to make these much needed social expenditures, particularly in health. India’s public health system remains limited in coverage. Out-of-pocket expenses are high, limiting affordability. This translates into poor (and unequal) health outcomes. Inequality adjusted life expectancy is 25 years while in many peer countries like Thailand and Vietnam there is only around 10 years’ difference between high and low-income individuals.

The way ahead

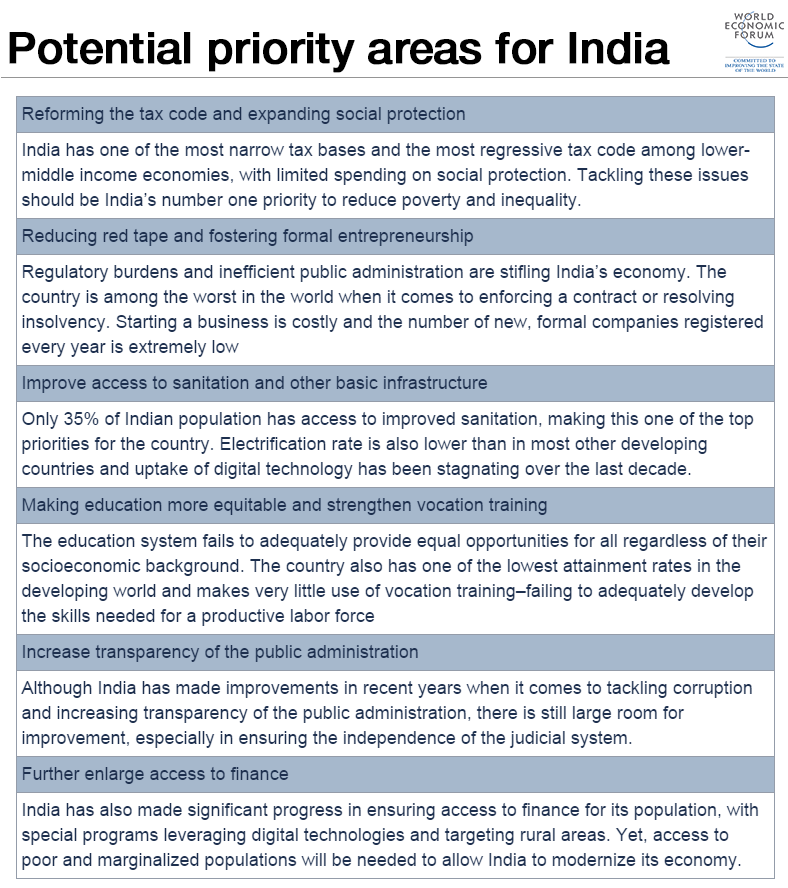

To achieve both economic growth and social inclusion, India should focus on a number of areas of reform, including:

Authors: Gemma Corrigan, Economist, Economic Growth and Social Inclusion Initiative, Inclusive Growth, World Economic Forum. Attilio Di Batisto is a Quantitative Economist at the World Economic Forum.

Image: Passengers ride an overcrowded bus as they head towards their village to celebrate “Dashain”. REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Jack Hurd and Florian Vernaz

May 21, 2025

Benjamin Wiener

May 21, 2025

Alejo Czerwonko

May 20, 2025

Matthew Wilson and Ratnakar Adhikari

May 20, 2025

Aengus Collins

May 14, 2025