3 reasons business leaders should care about the SDGs

Bhaskar Chakravorti

Senior Associate Dean, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts UniversityStay up to date:

Trade and Investment

This article is published in collaboration with Harvard Business Review.

The UN General Assembly held its regular meeting in New York this fall. But this year its purpose was different – and with significant implications for the future of the human condition. More than 190 member countries committed to “eliminate poverty in all its forms everywhere” by 2030, together with 16 other “big, hairy, audacious goals” — to use Jim Collins’ memorable phrase. Coming out of the meeting, the hashtag #2030Now, meant to drum up ground-level support, made a combined total of more than 1.6 billion impressions on Twitter and Instagram and was the top trending topic in the U.S. during the assembly. Cultural icons from Shakira to Queen Rania of Jordan were brought in to lend a certain pizzazz to the goals’ rollout.

If you are running a business, you’re probably asking right about now: “Why should I care?” I believe there are three reasons why you should.

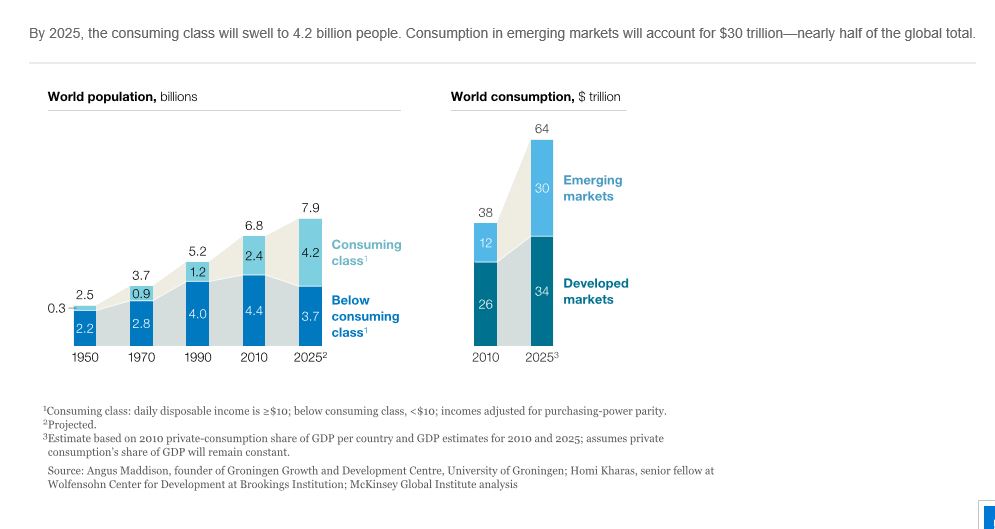

First, the global goals campaign represents a significant new opportunity for companies that view emerging and frontier markets as their source of long-term growth. According to estimates from McKinsey, consumers in these markets could be worth $30 trillion by 2025 — a significant step up from the 2010 value of $12 trillion. Since 2011, as emerging markets have suffered from slower growth and fresh social unrest, that $30 trillion prize seems more distant. Taking action on the global goals could help address several of these obstacles that are giving rise to “trapped value” in the emerging markets.

Second, with the public declarations by many companies to help with the goals, there is likely to be competitive pressure. Some companies could get a jumpstart in their industry in organizing partnerships and even positioning themselves as leaders in sustainable development using the goals as a branding anchor. Being slow to take action could lead to the risk of being left out of these relationships and a source of competitive disadvantage from a brand equity perspective.

Third, the goals cannot be realized without business participation. The price tag for accomplishing these global goals is estimated to be up to $3 trillion a year for 15 years. For most governments, financing the global goals campaigns will be a stretch; governments have already reneged in the past on commitments for similar targets.

The UN anti-poverty campaign had been boiled down to 5 P’s: Prosperity, People, Planet, Peace, and Partnership. But I see a missing sixth P: Profits. Businesses do stand to gain if they get involved in the right ways. And UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called directly on the business community to get involved:

I’m counting on the private sector. Now is the time to mobilize the global business community as never before. The case is clear. Realizing the Sustainable Development Goals will improve the environment for doing business and building markets.

My colleagues from Citi Foundation, Monitor Institute, and I have conducted research to understand the primary reasons behind why companies do and don’t invest in the kinds of sustainable and inclusive business activities embodied by the UN’s new campaign. The most frequently cited motivation was the mitigation of business risk from potential disruption of operations, supplies, or reputational damage, cited 38% of the time, followed by the motivation to adhere to industry norms of transparency, traceability, environmental responsibility, and other accepted standards, cited 27.6% of the time. Winning share in current markets and establishing a beachhead with future customers was cited 25.3% of the time. Building goodwill with key internal stakeholders was the least frequently cited motivation at 9%.

Our research also highlighted several common barriers. Some are external, such as weak infrastructure in emerging markets, lack of capacity among target customers and suppliers, and regulatory and policy complexities. Others are internal to the company: difficulty of monitoring, measuring, and communicating impact; alternative investment opportunities that take priority; long time horizons for profitable payback; and lack of clear funding mechanisms.

But innovating for sustainable development is actually quite close to the processes of “traditional” innovation. Unlike the case of the latter, where the benefits of innovation accrue mainly to the company, here the benefits are shared widely, potentially even with competitors. This can make the case for innovating in sustainable development more challenging.

Consider these examples of companies using sustainable development practices to enhance social good or strengthen their own business practices:

IMPACT 2030 is a recently launched business coalition designed to unite corporate volunteering efforts to address the global goals, with founding members that include the likes of IBM, UPS, GSK, Dow Chemical, Medtronic, Google, and Chevron, among others. A public commitment to such an effort creates an incentive to follow through. Furthermore, if membership of this club develops significant cache, then it becomes a powerful branding tool and a lever for competitive advantage.

Mars Incorporated, one of the world’s leading food manufacturers has two key initiatives that require active involvement with its supply chain and wider ecosystem: a genomics program to enhance the productivity of farmers in its supply chain and a move towards 100% certified sustainable sourcing. Simultaneously, it is keen to ensure that certification does not constitute an additional economic burden on the farmers. In order to find the right balance, Mars engages with the Rainforest Alliance to train farmers in sustainable cocoa practices. Moreover, sequencing the cacao genome led to Mars’ formation of the African Orphan Crops Consortium (AOCC) comprising African governments, companies, NGOs, and international agencies, to sequence and re-sequence the genomes of 101 African “back-garden” food and tree crop varieties crucial to 600 million people who live in rural Africa.

Olam, an agri-business with seed-to-shelf operations across 65 countries, has already organized its efforts around two of the global goals. These include Goal 2 (“End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture”) and Goal 17 (“Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development”). Specifically, Olam’s efforts to further these goals are in three areas: driving positive change in the communities in which it operates through its supply chains; partnerships with key organizations, including its customers, donor groups, and governments, that focus on sustainable development; and knowledge sharing to create opportunities to extend the impact beyond Olam’s direct zone of influence.

There are, of course, many challenges to a wider mobilization of private sector efforts around the UN global goals. One is that the UN-led exercise itself is too large and unfocused and loses momentum because there are far too many goals and targets and too much fragmentation of effort, which makes the task of coordination harder rather than easier.

But awareness of the challenges is the first step toward managing them. The UN global goals offer a new chance to bring global development issues to the surface. It also happens to offer a powerful mechanism to create multi-sector coordination on solving complex problems.

To my mind, the biggest risk with the project is if companies find it too lofty and too much of a “UN initiative” – and decide not try at all.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Bhaskar Chakravorti is the Senior Associate Dean of International Business & Finance at The Fletcher School at Tufts University.

Image: A man walks past buildings at the central business district of Singapore. REUTERS/Nicky Loh.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Sergio Navajas and Jimena Sotelo

May 29, 2025

John Letzing

May 29, 2025

Naala Oleynikova

May 28, 2025