4 common misconceptions about disruption from Clay Christensen

Stay up to date:

Innovation

This article is published in collaboration with Business Insider.

The terms “disruptive innovation” and “disruptive technology” are at risk of becoming meaningless buzzwords, according to Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, who introduced his theory of disruption 20 years ago.

As the number of “unicorn” companies, those valued at $1 billion or more, have captured the public’s attention, the cult of disruption has spread beyond Silicon Valley. Disruption was mentioned more than 2,000 times in articles last year — but most people get it wrong, he writes in the latest issue of the Harvard Business Review.

“Unfortunately, disruption theory is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success,” writes Christensen and his coauthors Deloitte director Michael Raynor and HBS assistant professor Rory McDonald. “Despite broad dissemination, the theory’s core concepts have been widely misunderstood and its basic tenets frequently misapplied.”

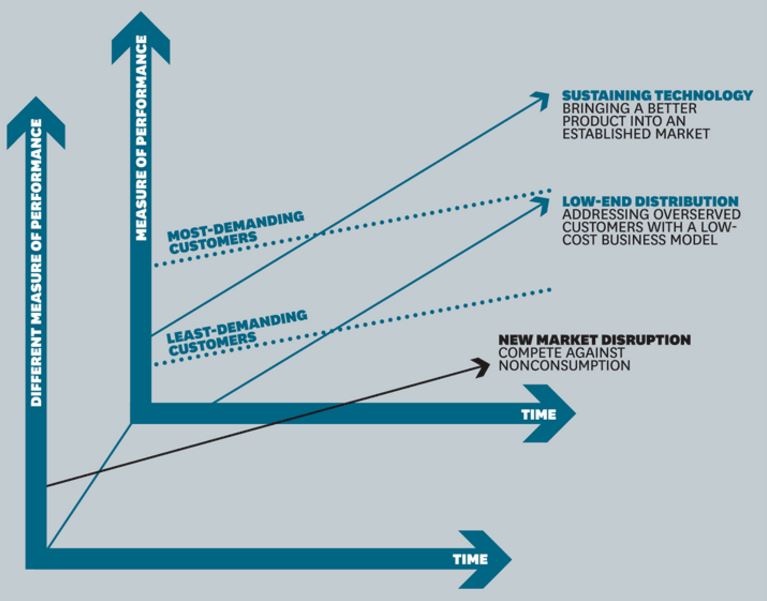

“Disruption” refers to the process that small companies can use to topple industry giants by grabbing a part of the market willing to sacrifice some quality usually for a cheaper price, and then moving upstream by adapting to a larger market.

Source: Harvard Business Review

Noting that “too many people who speak of ‘disruption’ have not read a serious book or article on the subject” and that the theory has been refined over the years, Christensen says there are four main points that are either overlooked or misunderstood that cause well-intending managers to make mistakes or critics to dismiss it entirely.

Here are the main points he would like to clarify:

1. Disruption is a process, not a moment in time.

Part of the problem, the authors write, is that people have come to think of companies disrupting an industry as soon as they enter with a new way of selling a product. But success through disruption doesn’t come quickly.

For example, one can consider Netflix’s disruption of the movie rental industry from its inception in 2002 to the demise of Blockbuster in 2012.

Netflix entered the industry by taking some of the market that was willing to wait a few days for a DVD to be mailed to their house in exchange for a much more affordable price than Blockbuster or other rental chains offered.

“The service appealed to only a few customer groups — movie buffs who didn’t care about new releases, early adopters of DVD players, and online shoppers,” the authors write.

Over time, it began to nab more customers from Blockbuster.

“[A]s new technologies allowed Netflix to shift to streaming video over the internet, the company did eventually become appealing to Blockbuster’s core customers, offering a wider selection of content with an all-you-can-watch, on-demand, low-price, high-quality, highly convenient approach.”

2. Disrupters typically utilize different business models, not just different products or services, from incumbents.

The authors point to the Apple iPhone as an example of using a business model to disrupt an industry.

Its initial success following its 2007 debut can be attributed to its product superiority in the smartphone market, but its lasting success was due to its disruption of the computer market, they say.

“The iPhone’s subsequent growth is better explained by disruption — not of other smartphones but of the laptop as the primary access point to the internet,” the authors write. “By building a facilitated network connecting application developers with phone users, Apple changed the game.”

3. Disruptive innovation does not guarantee success.

Critics point out that plenty of companies that Christensen deemed disruptive have failed. Christensen and his coauthors counter that the theory was never intended to be equated with success, saying it was intended to explain an approach to competition.

This is also the reason why some Silicon Valley entrepreneurs incorrectly deem rapidly growing companies to be “disruptive” regardless of their business model, they say.

4. A company does not necessarily have to disrupt its core offering when it is being disrupted.

The mantra of “disrupt or be disrupted” can be dangerously misleading, the authors argue.

“Incumbent companies do need to respond to disruption if it’s occurring, but they should not overreact by dismantling a still-profitable business,” the authors write. “Instead, they should continue to strengthen relationships with core customers by investing in sustaining innovations. In addition, they can create a new division focused solely on the growth opportunities that arise from the disruption.”

For example, Whole Foods has a small division devoted to online grocery delivery to compete with disrupters like Fresh Direct, but it won’t be dismantling its brick-and-mortar stores anytime soon.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Richard Feloni covers management strategy and entrepreneurship for Business Insider.

Image: A businessman walks in the financial and business district. REUTERS/Gonzalo Fuentes.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on BusinessSee all

Julia Hakspiel

June 17, 2025

Kalin Bracken and Sam Chandan

June 6, 2025

Michelle You

June 4, 2025

Apoorve Dubey

June 4, 2025

Michele Stansfield and Eva Borge

June 2, 2025