5 Arctic myths that need busting

Stay up to date:

Arctic

I’ve been asked many times if I have seen polar bears on my travels in the Arctic. And I have. But mostly I see humans. More than 4 million people live in the Arctic. There are cities and universities and an annual economy of roughly $230 billion dollars – equivalent in size to developed nations like Ireland or Portugal. People are very often surprised by these facts, thinking that the Arctic is nothing but ice and wilderness.

In its report Demystifying the Arctic, The Global Agenda Council on the Arctic outlines the common misconceptions that need busting if we are to get a fair and educated discussion on the development of the region.

1. The Arctic is an uninhabited, unclaimed frontier with no regulation or governance

In fact, the region is home to some 4 million people and a sizeable economy, all under the jurisdiction of eight countries (Russia, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Greenland/Denmark, Canada and the United States) with virtually no territorial border disputes between them. Even offshore in the Arctic Ocean, most coastal waters fall within existing Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) with further seafloor sovereignty extensions pending or likely under Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In Canada, Greenland and the US, local control by aboriginal communities and regional business corporations can be substantial. In short, the Arctic is neither an unclaimed, contested place nor a closed military zone, and is governed under existing national structures and international frameworks similar to other areas of the world.

2. The region’s natural resource wealth is readily available for development

Many technological, infrastructural, economic and environmental challenges impede natural resource development in the Arctic. Extracting resources is never a simple operation in polar environments, and resource development will require high levels of investment, including development of specialized technologies. Furthermore, the region is not homogeneous with regard to development potential. Strong distinctions exist between onshore and offshore environments, and between different regions and countries with regard to existing levels of infrastructure, population, environmental sensitivity and accessibility.

3. The Arctic will be immediately accessible as sea ice continues to disappear

On land, the opposite is true, owing to shorter winter road seasons and destabilized ground due to thawing permafrost. Even in the Arctic Ocean, sea ice is not the sole obstacle to shipping and maritime structures (such as drilling platforms). Other challenges include polar darkness, poor charts, lack of critical infrastructure and navigation control systems, low search-and-rescue capability, high insurance/escort costs, and other non-climatic factors. The related myth that climate change will create an ice-free Arctic Ocean year-round is also false, as sea ice will always reform during winter and ice properties and coverage will vary greatly within the region.

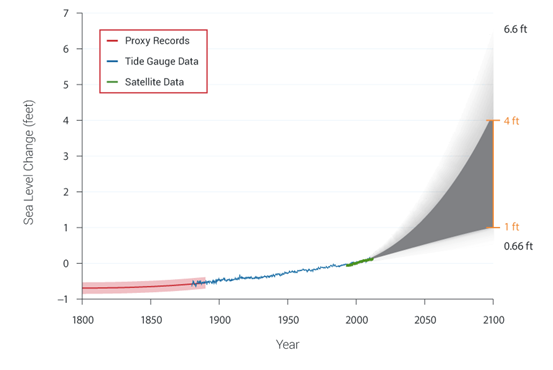

Chart showing the estimated, observed and possible future amounts of global sea-level rise from 1800 to 2100, relative to the year 2000. Source: Adapted from Parris et al. 2012 with input from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

4. The Arctic is tense with geopolitical disputes and the next flashpoint for conflict

The Arctic region is a powerful example of international collaboration, with the Arctic countries largely conforming to standard international treaties (e.g. UNCLOS), regional forums (e.g. The Arctic Council) and regular diplomatic channels to resolve their differences. The widely publicized sovereignty extension petitions now underway for the Arctic Ocean seafloor, for example, are science-based and not particularly controversial, with the relevant parties following the same UN procedure used to settle other continental shelf disputes around the globe.

5. Climate changes in the Arctic are solely of local and regional importance

The effects of global climate change felt by the Arctic have globally relevant repercussions, with numerous impacts flowing back to the rest of the world. These include: a faster sea level rise owing to greater ice loss from the Greenland ice sheet; altered weather patterns due to perturbation of jet streams; altered planetary energy balance as a result of lower light-reflectivity of formerly snow/ice covered surfaces; increasing greenhouse gas emissions from thawing permafrost soils and methane hydrates; and the psychological loss of globally iconic species such as the polar bear. Within Arctic countries, especially Canada, Russia and the US, reduced winter road access over frozen water and ground presents non-trivial socioeconomic costs to Arctic populations, transportation networks and global commodity markets.

For more information, see our reports, Demystifying the Arctic and Five Arctic Myths.

Have you read?

3 industries that will be hit by Arctic change

6 charts to help you become an Arctic ice expert

5 reasons to care about Arctic summer sea ice

Author: Sturla Henriksen is the CEO of the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association and the business community engagement work stream lead in the Global Agenda Council on the Arctic.

Image: Fishing boats sit in the harbour in the town of Uummannaq in western Greenland March 18, 2010. REUTERS/Svebor Kranjc

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025