How much retirement income is enough in your country?

Stay up to date:

Civic Participation

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate.

Over the rest of the twenty-first century, the global human population is expected to keep growing; more important, it will keep growing older. By the year 2100, the United Nations expects there to be more than ten billion of us, up from 7.3 billion today. In the meantime, the number of people older than 60 is expected to double by 2050 and more than triple by the end of the century.

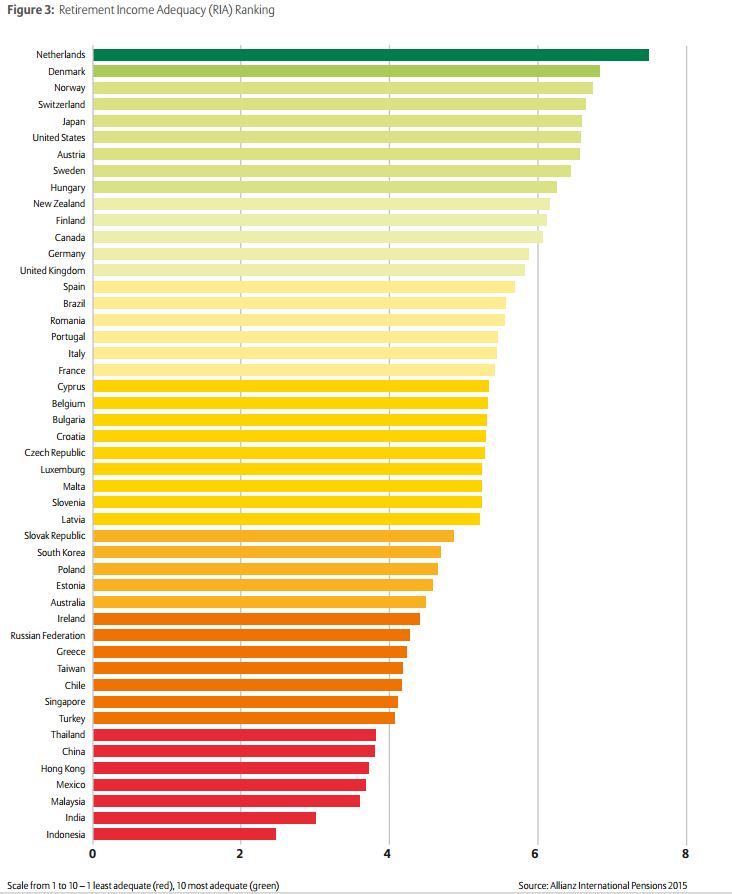

As societies around the world prepare for swelling numbers of retirees, the policy challenge will be to ensure the financial sustainability of pension systems while guaranteeing adequate incomes for those no longer working. Today, according to recent research by Allianz, only four countries appear to have achieved this: Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, and New Zealand.

Previously, we analyzed the sustainability of the pension systems of 50 countries. Many of the countries that performed poorly on this test – most notably France, Greece, Italy, and Spain – were European welfare states where generous public pensions place heavy burdens on national finances. In 2010, the European Union’s expenditure on public pension systems amounted to 11.3% of GDP. This is expected to rise to 12.9% of GDP by 2060. Similar burdens can be observed in Japan and Brazil, indicating a substantial need for reform there as well.

By contrast, many of the countries that ranked highly in our sustainability rankings did so because their public pensions systems covered only the bare minimum necessary to keep retirees out of absolute poverty. These include top-ranked Australia, as well as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland. In these countries, retirees will need additional forms of savings and income in order to maintain the standard of living to which they are accustomed.

The first study provided us with information about governments’ ability to maintain their commitments. We have now sought to take into account whether those commitments would prove adequate to the needs of retirees.

There is no simple way to measure the adequacy of a pension system. Possible thresholds include the poverty line, a percentage of pre-retirement income, or a certain standard of living. While alternative sources of income and wealth can make retirees less reliant on public systems, elderly people’s special spending needs can increase the need for resources. The definition used in our research attempted to strike a balance, taking into account alternate sources of wealth and income as well as expenditures relevant to old age.

When it comes to adequacy, mature pension systems in developed countries perform well. The Netherlands topped our list, followed by Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, Japan, and Austria. These countries mostly provide robust public pensions, supported by other income streams and non-pension wealth, and benefit from longer working lives and lower health-care spending.

Notably, not all countries that scored well on sustainability were highly ranked when it came to adequacy. On the contrary, performing well on both measures was the exception.

Australia, for example, is at the top of the list for sustainability, but ranks 35th out of 50 for adequacy. Workers in Australia retire early, often have limited non-pension wealth, and face substantial living costs. Superannuation – a government-mandated private savings plan – does not yet have enough assets to compensate for the country’s relatively parsimonious public pension system. The problem is aggravated when people take lump-sum payments and do not transform their assets into an income stream for retirement. In short, Australia’s pension system may be sustainable, but it is unlikely to meet its retirees’ needs.

Since the 1990s, many countries have introduced major pension reforms, by and large moving in the same direction: sharing risk among governments, companies, and individuals in a more balanced way. These efforts are to be commended, but they also need to be strengthened if more countries are to join Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, and New Zealand in having pension systems that are both sustainable and adequate.

As societies age, the delicate balancing act between caring for today’s pensioners while ensuring the rights of future generations will become more difficult – and more important. Failure would result in overburdened and unsustainable public finances, and would expose a significant and growing group of voters to acute poverty. As any pension saver knows, the time to prepare for the future is now.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Brigitte Miksa is Head of International Pensions at Allianz Asset Management.

Image: A woman looks at a window display on Oxford Street in central London. REUTERS/Olivia Harris

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Jake Yu

November 10, 2025

Marco Lambertini and Marcelo Bicalho Behar

November 6, 2025

Souleymane Ba and Nakul Zaveri

November 4, 2025

Aimée Dushime

November 4, 2025

Junpei Guo

October 30, 2025

Dylan Reim

October 29, 2025