Why gender inequality is worse than you think

Stay up to date:

Global Governance

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate.

The high cost of gender inequality has been documented extensively. But a new study by the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that it is even higher than previously thought – with far-reaching consequences.

The McKinsey study used 15 indicators – including common measurements of economic equality, like wages and labor-force participation rates, as well as metrics for social, political, and legal equality – to assign “gender parity scores” to 95 countries, accounting for 97% of global GDP and 93% of the world’s women. Countries also received scores for individual indicators.

Unsurprisingly, high scores on social indicators correspond with high scores on economic indicators. Moreover, higher gender-parity scores strongly correlate with higher levels of development, as measured by GDP per capita and the degree of urbanization. The most developed regions of Europe and North America are closest to gender parity, while the still-developing region of South Asia has the furthest to go. Within regions, however, there are significant disparities, owing partly to differences in political representation and policy priorities.

One overarching conclusion of the McKinsey study is that, despite progress in many parts of the world, gender inequality remains significant and multi-dimensional. Forty of the countries studied still exhibit high or very high levels of gender inequality in most aspects of work – especially labor-force participation rates, wages, leadership positions, and unpaid care work – as well as in legal protections, political representation, and violence against women.

The costs of this inequality are substantial. If women matched men in terms of work – not only participating in the labor force at the same rate, but also working as many hours and in the same sectors – global GDP could increase by an estimated $28 trillion, or 26%, by 2025. That is like adding another United States and China to the world economy. Closing the gender gap in labor-force participation would deliver 54% of those gains; aligning rates of part-time work would provide another 23%; and shifting women into higher-productivity sectors to match the employment pattern of men would account for the rest.

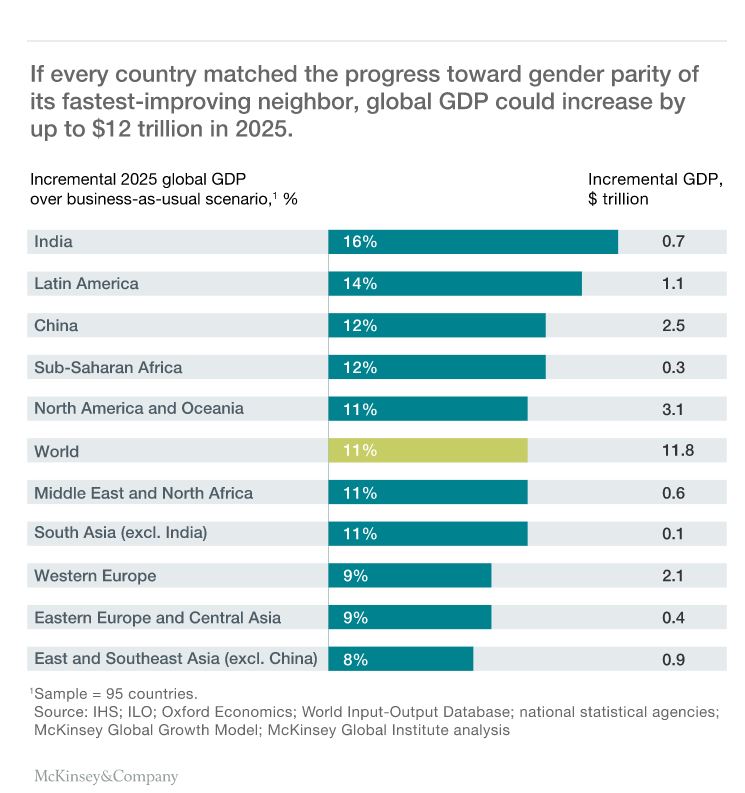

Given recent rates of progress, it is unrealistic to expect full gender parity in the world of work in the foreseeable future. But countries could match gains in the best-performing economy in their region. That would add up to $12 trillion to global GDP by 2025, boosting GDP by 16% in India and about 10% in North America and Europe.

To achieve this, the McKinsey study recommends that governments, non-profits, and businesses emphasize progress in four key areas: education, legal rights, access to financial and digital services, and unpaid care work. As these critical and mutually reinforcing efforts boosted women’s economic standing, they would naturally help to improve women’s social position, reflected in better health outcomes, increased physical security, and greater political representation.

The first step is improved education and skills training, which have been proven to raise female labor-force participation. Smaller differences in educational attainment between men and women are strongly correlated with higher status for girls and women, which helps to reduce the incidence of sex-selective abortions, child marriage, and violence from an intimate partner. Women who enjoy parity in education are more likely to share unpaid work with men more equitably, to work in high-productivity professional and technical occupations, and to assume leadership roles.

To reinforce such progress, legal provisions guaranteeing the rights of women as full members of society should be introduced or expanded. Such provisions have been shown to increase female labor-force participation, while improving outcomes according to several social indicators, including violence against women, child marriage, unmet need for family planning, and education.

Improved access to financial services, mobile phones, and digital technology is also linked to higher rates of female labor-force participation, including in leadership roles, and decreased time spent doing unpaid care work. And, as it stands, women spend a lot of time on such work, accounting for 75% of it, on average, worldwide.

Unpaid care work – which includes the vital tasks that keep households functioning, such as looking after children and the elderly, cooking, and cleaning – obviously amounts to a major hurdle to more active participation in the economy. If men shared such responsibilities more equitably, businesses adopted more flexible and “care-friendly” work schedules, and governments provided more support for childcare and other family-care functions, female labor-force participation rates could rise significantly.

It is certainly in the interest of companies to do more to support gender equality, which expands the pool of talent from which they can select employees and managers. Moreover, more women mean more insight into the mentality of female customers. And, perhaps most important to a company, a growing body of evidence suggests that the presence of women in executive and board positions can increase corporate returns.

One of the highest barriers to gender parity, however, may be deeply held beliefs and attitudes. As Anne-Marie Slaughter emphasizes in her recent book, both men and women undervalue care work relative to paid work outside the home. Likewise, surveys indicate that sizeable shares of men and women worldwide continue to believe that children suffer when their mothers work. And numerous studies document continued implicit biases against women in hiring and promotion processes, triggering growing interest in Silicon Valley startups that use technology to mitigate such biases throughout their human-resources operations.

Clearly, reaching gender parity will be no easy feat. But it remains vitally important, both to improve outcomes for women and girls, and to advance economic development and prosperity for all.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Laura Tyson is a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. Anu Madgavkar is a senior fellow at the McKinsey Global Institute.

Image: Students attend class on the first day of the new school term. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Aarushi Singhania and Kiva Allgood

July 4, 2025

Abayomi Olusunle

July 1, 2025

Kate Whiting

June 25, 2025