What does climate change mean for the future of trade?

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

The climate talks concluding in Paris have often been seen as being about the environment. But they are about much more: COP21 is a crucial summit about the future of international trade.

The Paris outcome will affect the ability of trade to foster growth, create jobs and boost development. It will also determine the power that trade will have to fight poverty in the future.

The reason is simple: in developing countries, rural communities – where most poor people live today – rely heavily, if not almost exclusively, on their natural habitat and resources for income, food, fuel and shelter. Their habitat determines what they produce and what they can trade. But due to climate change, this habitat is now being altered, sometimes dramatically. For example:

- In the Horn of Africa in 2011, a drought-induced famine affected more than 10 million people

- In Latin America, climate change is to blame for the rapid expansion of a fungus, which attacks coffee plantations, killing trees

- In Africa and Asia, where tourism is a critical source of revenues, particularly for least developed countries, climate change has increased the likelihood of beauty spots such as coral reefs being wrecked, discouraging tourists

- In coastal areas around the globe, fish stocks are not only dwindling because of overfishing, but also because of ocean acidification caused by rising sea temperatures

Almost everywhere, there is an unprecedented loss of biodiversity. According to some scientists, the current pace of plant and animal loss means that by the end of the century, 20% to 50% of all living species on earth could be gone forever. By 2070, some reports estimate that climate change could reduce total crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa by as much as 20%.

With climate change, the prospects for rising out of poverty by producing and trading the yields from land, forests or seas will become all the more difficult.

But, climate change is also affecting the world’s capacity to trade.

Around 80% of global trade by volume and over 70% by value is carried by sea and is handled by ports. But many ports, especially in developing countries, are not ready to withstand stronger and more frequent storms or rising sea levels. For example, the sea off the coast of Tanzania is projected to rise by 70 centimeters by 2070: this would devastate the port city of Dar es Salaam, a major player in East African trade and a lifeline for Tanzania and nearby countries. Transport systems – the arteries of trade – are not prepared to cope with climate change.

So what can those who deal with trade and trade policy do? How can trade and trade policy be properly deployed to meet the challenge of climate change?

Firstly, there must be an end to trade distortions, subsidies, or similar trade incentives that prop up wasteful and unsustainable economic activities.

Tendencies to erect new barriers against renewables, including biofuels, must be tackled. More stringent conditions are needed for the imposition of trade measures, such as trade defense instruments, that work against “green growth” even when these are claimed to serve the interest of certain “green jobs”. Similarly, fossil fuel-subsidies have no place in a climate-friendly economy. Neither have those fish subsidies that deplete already critically strained fish stocks.

Secondly, the positive contribution that trade can make to reducing carbon-emissions must be enhanced. Trade and investment are key channels for technological diffusion, and also important means for transforming the structure of economies, and diversifying them. Open trade, if priced correctly, can create the right incentives for producers to improve efficiency and cut waste.

The world needs to better use the power of trade for our common good. One way of doing so is to create an open global market in environmental technologies. Import tariffs in some countries on products such as solar water heaters are still more than 20% and wind turbines more than 15% – much higher than the world average tariff of per cent. Dismantling such tariffs can make environmentally friendly products and technologies cheaper and more accessible, especially in developing countries.

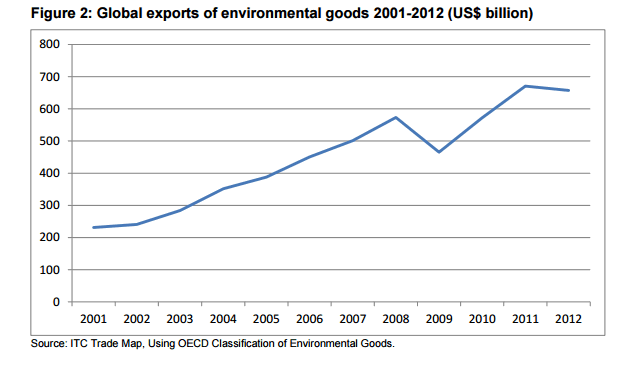

Environmental exports are already valued at about $670 billion, and this would increase dramatically if exports of green goods and services from developing countries were promoted.

Global exports of environmental goods 2001-2012 ($ billion)

More emphasis should be given to the commercialization of biodiversity, be it through tourism or BioTrade initiatives that create the right market incentives for nurturing and preserving biological resources everywhere, particularly in poorer countries and rural communities. For example, by 2050 sustainable global business opportunities in natural resources could, according to some estimates, amount to $2 trillion to $6 trillion. And, the industry is expected to grow even further in the next 25 years.

International production networks also need to go green. Intra-firm trade dominates global trade today and is also its fastest growing segment. But it can potentially blur the environmental impact of different stages in the production cycle. Increased environmental transparency across supply-chains is therefore necessary, combined with helping poorer producers to meet higher standards, to put a market premium on doing the right thing.

In addition, private investment in sustainability in developing countries needs to be mobilized. The current gap in investments necessary to meet the Sustainable Development Goals has been estimated at approximately $2.5 trillion annually for developing countries alone. Financial markets, not least stock exchanges, can play a pivotal role. By requiring environmental and social governance performance reporting by publicly listed companies, stock exchanges can funnel more resources to sustainability sectors, as well as better reward those companies that invest in climate adaptation and mitigation.

It also needs to be recognized that current aid programmes such as Aid for Trade, although significant, will not be enough to deal with climate-induced trade disruptions. Additional climate finance is required to manage the transformation of economic activities in developing countries, and the transformation of our trade and transport infrastructure, to new man-made realities.

Fighting climate change is the fight of our generation. This is equally a fight for trade policy-makers, because climate change jeopardizes global trade as we know it and as we have come to profit from.

Have you read?

What role will fossil fuels play in our low-carbon future?

5 steps to save Africa from climate change

5 things Europe must do for a renewable future

This text is based on speech delivered at COP21 on 9 December 2015.

Author: Joakim Reiter, a former ambassador of Sweden to the World trade Organization, has been Deputy Secretary-General of UNCTAD since April 2015.

Image: Baskets containing acai berries sit on the dock near the boats that brought them to Ver-o-Peso market in Belem January 11, 2012. REUTERS/Paulo Santos

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Forum Stories

May 30, 2025

Nigel Topping and Gonzalo Muñoz

May 28, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

May 27, 2025

Daniella Diaz Cely

May 27, 2025