How is China's stockmarket turmoil affecting Asia?

Image: A customer holds a 100 Yuan note at a market in Beijing. REUTERS/Jason Lee.

Stay up to date:

Banking and Capital Markets

A shocking start to the year for China’s financial markets has resulted in the rest of Asia faring little better.

Worldwide interest in China’s markets and economy is shining a spotlight on the region’s other markets as investors and analysts test links with mainland assets that in some cases are new and developing.

Until recently, Asian markets tended to track closely the lead provided by Wall Street, even as local economies increased exposure to their giant neighbour. Now fears about China are weakening US stocks, and further weighing on Asia itself.

“We’re in an environment where the market here is sensitive to slowing growth and downwardly revised expectations,” says Timothy Moe, Goldman Sachs’s chief Asia-Pacific equity strategist.

“Against that backdrop you’ve got fears about growth in China then being fanned by stocks falling and the renminbi depreciating.”

There was no respite on Monday. Falls in Shanghai and Shenzhen took their losses so far this year to 15 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively.

Hong Kong’s Hang Seng is now down 9.2 per cent this year, Japan’s Topix is off 6.5 per cent and Taiwan’s Taiex has fallen 6.6 per cent. For the broader MSCI Asia-Pacific, 2016 ranks as the poorest start since 2000.

“We knew we were living in difficult times but we didn’t imagine the risks would come home to roost so early in the year, and so brutally,” says Manishi Raychaudhuri, Asia equity strategist at BNP Paribas.

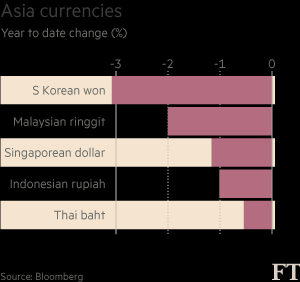

Regional currencies have also suffered, with the Korean won falling 3.1 per cent against the dollar and the Malaysian ringgit 2.1 per cent weaker.

The losses across asset classes have left investors scrambling to understand better how China actually interacts with its neighbours.

“There was a view for a lot of last year that the worst was behind us and that a Fed hike wasn’t to be feared given the significant adjustment we’d already had,” says Jonathan Garner, chief Asia and emerging markets equity strategist for Morgan Stanley. “But people are not as underweight as was thought.”

Hong Kong has so far been the epicentre of reaction. Just on Monday, the short-term cost of borrowing offshore renminbi spiked sharply higher — thought to be largely a side-effect of China’s suspected intervention in the offshore market in the past week.

Offshore renminbi rates have limited real economic impact; however, analysts are also exploring more direct connections between the mainland and its offshore hub.

The Morgan Stanley team, for example, calculates that every 1 per cent fall in the renminbi’s value against the dollar translates into a cut of just over 1 per cent in reported earnings for the Hong Kong China Enterprises index, the main measure of the Hong Kong shares of mainland companies.

With China’s markets still largely closed to outsiders, indices such as the HSCEI have become key proxies for China bets and feature in a range of products from futures to index-linked derivatives.

Mohammed Apabhai, head of Asia-Pacific trading strategies at Citigroup, cautions that there is also the potential for particular products to move markets.

So-called “autocallables”, index-related bets that an offer an attractive yield unless the underlying market falls to a specified level, have proved popular in markets such as Korea. Many of these are based on the HSCEI.

“You can imagine if the market is down 5 or 6 per cent in a day then suddenly there is some futures selling that emerges, that is going to have a pretty big impact,” says Mr Apabhai.

“If you woke up tomorrow and you saw the HSCEI down 12 per cent [and] if you didn’t know about these products what you’d automatically imagine is that this is it; this is the big China credit crisis that everybody’s been waiting for, when actually it may be nothing of the sort and it may just be a technical selling.”

In the meantime, analysts are also digging into more direct economic links given China’s growing importance as a trading partner.

Northern Asia is likely to be hardest hit by any further slowdown in China. Goldman Sachs strategists estimated that the mainland accounts for 10-15 per cent of overall listed companies’ sales in the region.

On an exports basis, Taiwan and Hong Kong are particularly at risk. Both send more than a third of their gross exports to their giant neighbour and within that, value-added sales to China are worth more than 10 per cent of their respective gross domestic product.

Data are not so far helping ease the negative mood. Soft inflation data from China at the weekend underscored the general easing of price pressures across the region.

“First, it makes the already high level of debt harder to service, hurting demand,” says Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economics at HSBC. “Second, it reduces the potency of any further monetary stimulus. Marginal rate cuts may still arrive in the coming months, including in Korea, China, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand and India. But they’ll not pack much punch.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Agshin Amirov and Azar Hazizade

September 19, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi

September 17, 2025

Dante Disparte

September 17, 2025

Kahlil (KB) Byrd and Alexis Crow

September 16, 2025

Mark Gough and Naoko Ishii

September 15, 2025

Eneida Licaj and Genevieve Sherman

September 10, 2025