Which country will be the first to close the gender gap – and how?

Image: REUTERS/Michael Buholzer

Vesselina Stefanova Ratcheva

Head of Metrics, Communication Strategy and Coordination, World Economic ForumSaadia Zahidi

Managing Director, Centre for the New Economy and Society and Knowledge Communities, World Economic ForumStay up to date:

Gender Inequality

This piece is part of an in-depth series on Women at Work. For regular updates on gender issues ‘like’ our Facebook Page and sign up to The Gender Agendaweekly email digest.

Ten years ago the World Economic Forum started benchmarking gender gaps across the world. Each year, our annual report provides the global community – governments, companies and individuals – an opportunity to compare the relative position of women and men in economies across the globe.

As we reflect on a decade of data, we can make an educated guess on where gender gaps will close first, ceteris paribus. For 109 countries, sufficient historical data is available from the Global Gender Gap Index to calculate rates of change and estimate future trends. The projections are indicative of which countries are making the fastest progress on closing gender gaps, and where there may be a risk of stalling. While the rankings and the projections derived from them compare the position of women and men on education, economic, political and health indicators within a country, parity within each country does not mean parity of outcomes between countries.

Iceland is set to be the first country in the world to close the gender gap in just 11 years. The United States and Germany are both set to close their gender gaps in more than 60 years, longer than countries which are currently ranked lower. Slovenia is likely to close its gender gap before Germany or Switzerland. Similarly, while Sweden ranks highly, akin to other Nordic states, change over the past 10 years has been slow. While in 2006, it was the best country for gender equality, its recent progress suggests it will be one of the slowest to close its gender gap in the future.

Still, past rates of change need not hold true in the future – they only provide a sense of the countries’ trajectories to this point of time, relative to their starting point. Change can be accelerated using appropriate public policy measures, an improvement in the enabling environment provided by businesses, and more breadth in the roles and identities available to women in wider society.

The most striking changes have occurred in how and where women are integrated into the global talent value chain – from education through to labour market opportunities.

A hundred years ago, women were still unable to vote across most countries in the world. Today, they make up the majority of those in university in nearly 100 of the world’s biggest economies. Many governments have sought to win the returns of this investment by introducing policies that help make female labour force participation feasible and an option which makes economic sense – for employers, individuals and families. Effective interventions have ranged from legislation promoting non-discrimination in hiring, appropriate paternity leave, child subsidies and tax credits, gender neutral taxation for families, as well as quotas in economic and political life. Mixed parental leave policies in particular, rather than pure maternity leave, have begun to enable a more equitable division of labour between the sexes when it comes to child-rearing. Some governments have delivered a further disruptive jolt to the business community by legislating gender equality targets at different senior level positions, with a particular emphasis on boards.

And they have been informed by – indeed supported by – pioneering companies that have already gone a step beyond pure compliance. These companies have embraced new hiring and managerial practices which have enabled them to better promote and leverage female talent. Some businesses have further pursued the cause of promoting a more gender equal society by influencing the status of women along the value chain of their suppliers, distributors and partners. Recognizing the need to ensure women have the opportunity to work, businesses have also engaged with civil society to improve the position of women in society more broadly, promoted gender neutral images of women in their advertising, and actively campaigned with girls and young women in schools and universities to consider careers in their sectors.

Successful companies have effectively introduced more transparency as part of internal measurement and monitoring – allowing them to understand their own gender gaps. They have built awareness and accountability among their senior staff, and provided training on understanding biases in management styles. Businesses have also seized the opportunity of the overall disruptions in the structure of work – work 2.0 – to empower female workers by offering flexible work and transparent career paths.

In addition, the social reproduction of gender stereotypes – nurture in the family environment, socialization in school and work, and media images – often means there is also a need for specific training and initiatives targeted at high-potential female leaders and a number of companies have supported their female workers by providing this form of training, mentoring and sponsoring. In parallel, pioneering voices have asked women to take on the personal work of leaning into the offer of career progression.

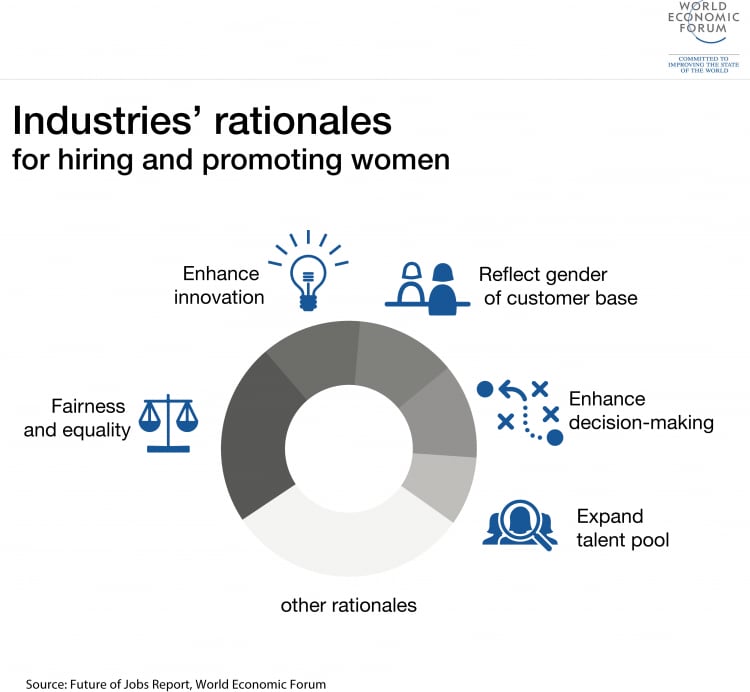

Although many employers have invested time and effort in these endeavours out of a strong belief in the value of fairness and equality for the social good, there is a significant part of the business community which has recognized the benefits of including women because of its effects on innovation, decision-making, diversity and their bottom line. This “business case” is compounded by the growing incomes of women – and the customer base they represent – as well as the rapid rise of women in tertiary education – and the growing talent pool they represent.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Challenge Initiative on Gender Parity works with governments and business to accelerate progress on gender parity, particularly on education and economic gender gaps. So what – if any – of these numerous strategies have worked best? While no individual practice or policy provides a silver bullet, it is clear that countries that have successfully closed their gender gaps have deliberately used a combination of these systemic levers of change. The same holds true in companies – companies that have succeeded have not relied solely on CEO leadership or HR-driven change or corporate social responsibility initiatives, but rather sought to put in place a holistic combination of practices to create change.

On this International Women’s Day, one critical message we can all carry forward is that accelerated change is entirely possible – but a search for deep collaboration between sectors and within organizations is likely to yield more results than any one practice or policy.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Zainab Azizi

April 9, 2025

Jon Jacobson

March 27, 2025

Andrea Willige

March 26, 2025