Women and work. The system is broken, so how can we fix it?

Image: REUTERS/Giorgio Perrottino

Stay up to date:

Gender Inequality

It will be 118 years before women have the same career prospects as men. No country in the world has closed its gender gap. Even as female leaders steer multinationals and major economies, the reality in 2016 is a working world which still excludes, underpays, overlooks and exploits half of its available talent.

Why is this happening? It’s been over a hundred years since women first gained suffrage (New Zealand gave women the vote in 1893) and we’re over half a century on from equal pay legislation (the United States made wage discrimination illegal in 1963).

Where have all these years of social progress and political change got us? Only this far.

This month, for International Women’s Day, we’re showcasing a series of articles that unpick the complex reasons behind the woeful rate of progress for working women.

A picture emerges of insidious biases both in our heads and at the heart of our institutions, in the way we see the world and in the way the world values work and care.

The problem in our heads

Female coders are rated better than men – except when people know they’re women. Male biology students rate their female peers as B grade, even when they get As. I’ve read enough research to be depressed all year, and it’s only March. Tinna Nielsen, an anthropologist and behavioural economist (and a World Economic Forum Young Global Leader) sheds light on what’s going on in an essay on subconscious bias.

Business leaders know that female leadership boosts profits (typically by 15%, according to EY). They know it’s logical to promote women. But all the logic in the world won’t work if we’re not aware that the rational bit of our brain isn’t running the show. Nielsen cites research showing that the unconscious mind “dominates about 90% of our behaviour and decision-making, and this system is instinctive, irrational, emotional, associative and biased.” Which means – bad news.

“At the moment, we are talking to the wrong system of the brain and we are speaking the wrong language.”

She suggests a series of “nudges” to tackle this, including “flipping the numbers”, so instead of targeting 30% women in leadership, you ask that a senior team has a maximum 70% members of the same gender.

This view – that gender parity is failing not because of a lack of goodwill, or good policy, but because of the way hidden cultural factors silently play out – resonates with Jonas Prising. In an essay titled “How to be a male feminist at work”, the CEO of recruitment company ManpowerGroup writes:

“I don’t think most male leaders are intentionally biased against their female colleagues, but we do need to take a hard look at the culture we create and whether it is aligned to produce the results we want. If you have no female candidates for your organization's top jobs, it’s probably time to look in the mirror.”

Earlier this year, at Davos, Jonas Prising shared the stage with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who confronted this problem head-on last year when he unveiled a 50-50 quota in his new cabinet – “because it’s 2015”. In the same Davos session, Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg revealed that our subconscious biases are so reflexive that they even influence the way we reward our pre-schoolers. Yes, readers: we have a toddler wage gap:

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Meanwhile, in a new essay for Agenda, Beth Brooke-Marciniak, Global Vice Chair of Public Policy at EY, throws a curveball at the problem. You need women who are competitive enough to get to the top? Hire athletes. And learn from the lessons of sport. She writes:

“I’m convinced my sports background equipped me to succeed even though I was so very different from my male colleagues – an introvert in a world that values extroverts, a progressive in my politics and a lesbian.”

Could it be a coincidence that Christine Lagarde was a synchronized swimmer, Michelle Bachelet (the first female president of Chile) a volleyball player and Condoleeza Rice (former US secretary of state) a figure skater?

The problem in our homes and in our workplaces

While all these perspectives offer some hope for women leaders to pull ahead, what about the rest of the workforce? What about the deeper divides that mean women face the dual burden of paid work and unpaid care, that they are particularly vulnerable to abuse and that they make up the majority of the world’s working poor?

From garment workers fired for being pregnant in Cambodia to domestic workers shut out from any form of legal protection, Nisha Varia of Human Rights Watch offers a chilling view of systematic exploitation. Meanwhile, Sharan Burrow, head of the ITUC, takes on the issue of unpaid care:

“Globally, women spend at least twice as much time as men on unpaid care work, including domestic or household tasks, as well as care for people at home and in the community.”

She calls for care to be more comprehensively valued, with government-funded professional care to both create jobs in that sector and allow women to participate in the workforce, meeting a G20 target to increase female employment rates by 25%. According to her research, an investment of 2% of GDP in seven countries would create over 21 million jobs.

The traditional delineation between breadwinners and caregivers has gone. Dual-income households are the norm, female bread-winners are on the rise, and families reliant on just one parent – often women – are increasingly common, explains Saadia Zahidi, the World Economic Forum’s head of gender parity. But labour policies and business practices have not caught up:

This chimes with Anne-Marie Slaughter, president and CEO of the New America Foundation, who in this Agenda article calls for nothing less than the “disruption” of the modern workplace:

“Making room for care in the workplace requires assuming that all workers are or will be caregivers at some point in their working lives.”

She suggests some concrete solutions, from the US Navy’s “career intermission” programme to corporate work coverage plans to better manage absences.

If there’s any kind of organization that should have cracked this, you would have thought it would be our universities: beacons of enlightenment and progress. They should be role models on gender parity, right? Wrong. Only 14% of the world’s top 100 universities are led by women. In a frank essay, Peter Mathieson, the President of Hong Kong University, confronts the status quo:

“The hypothesis that I explore in this article is that my chromosomal make-up has given me an unfair advantage in all the roles in which I have worked. Being male has allowed me to have a family without it impeding my career, to travel extensively, to interact with other males on an equal footing and possibly to earn more money than an equivalently-qualified female would have done.”

He writes that seeing care as women’s work is “a cultural norm that can be challenged and changed,” and calls for closer examination of the gender gap in academic leadership.

The path ahead

While the workplace of today needs fixing, we’re rushing towards a future where the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” is both creating new opportunities and destroying old ones. Elsie Kanza, head of Africa at the World Economic Forum, explores how to ensure African women are reaping the digital dividend, including a project to train school girls to build satellites. Naadiya Moosajee, a South African civil engineer who co-founded a non-profit training other women as engineers, is optimistic:

“Already we’re seeing the shifts of women from consumers of technology to designers and coders, creating demand and matching unmet demands.”

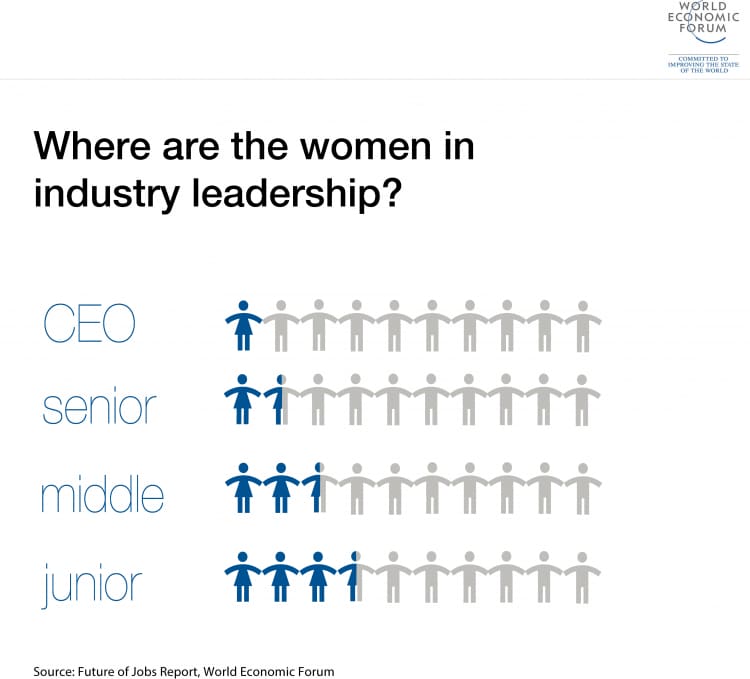

From paid care to cabinet quotas, from satellites to sport, I hope this series provides insight and inspiration on how we can finally get closer to achieving gender parity at work. Because if there’s one thing that’s clear, it’s that goodwill alone is not enough to nudge us on from today’s dismal rate of progress. As long as we allow our own inner biases to go unchecked, as long as we keep expecting women to excel at work and exhaust themselves at home, then leadership is inevitably always going to look a bit like this.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Aarushi Singhania and Kiva Allgood

July 4, 2025

Abayomi Olusunle

July 1, 2025

Kate Whiting

June 25, 2025