Can we teach girls confidence in the classroom? A lesson from East Asia

We're putting a limit on girls' dreams. We're training them to think their ideas don't matter

Image: REUTERS/Beawiharta

Stay up to date:

ASEAN

That afternoon, a teacher and I left the fifth-grade classroom with so much zest. The discussion had been dynamic and the students’ enthusiasm was evident. It was what teachers call a good day. Nonetheless, one uneasy thought remained at the back of our minds. It was mainly the boys who talked. They expressed their ideas and they voiced their concerns. Meanwhile, the girls stayed quiet and kept their thoughts to themselves.

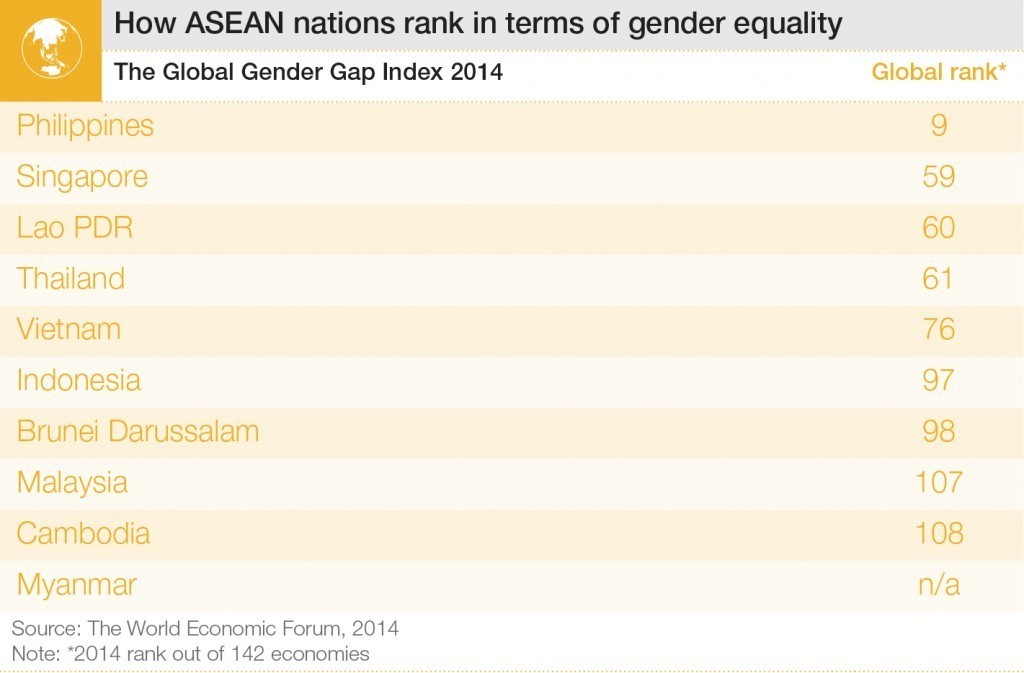

The Association of Southeast Nations – more commonly known as the region of ASEAN – is growing rapidly. This is due to multiple factors, but dominant among them are technological advancement and the region’s young demographic. Discussions about social and economic development cannot be separated from the debate about education, in particular the agenda for girls’ education.

Countries experience more significant progress when women are part of the economy – and for these women to be part of the workforce, they have to be well educated.

Using Indonesia as an example, we can see that the region is off to a good start. In primary schools, the number of boys and girls is about the same. But this starts to change when the children transition to secondary school. Data from the Ministry of Education shows that girls are more likely to drop out than boys. As a result, the education rate for girls continues to decline as we move towards higher stages of education.

The danger of low expectations

While parents might perceive their children equally at young age, they start to have different expectations as the children grow up. It’s often presumed that boys will carry the responsibility of being the family breadwinners. It’s common for girls to be expected to get married, have children and take care of the household. In a developing economy, where resources can sometimes be limited, it’s often sons who are prioritized. The gender pay gap doesn’t help, either; with similar academic qualifications, men earn so much more than their female colleagues.

These factors affect how far girls see themselves progressing. Knowing that they will probably end up taking care of a family, many girls view school as a formal rite of passage. They don’t see it as a learning journey through which they can explore their potential. This ceiling is present not just in lower socio-economic families with limited finances: even women with university degrees on the management trainee programme of a multinational company can feel they’re just passing time until they get married.

Such a ceiling puts a limit on girls’ dreams. It leads them to become less confident in public spaces, such as in the fifth-grade classroom we just walked out of. It also trains them to think that neither their ideas nor their long-term visions matter, because society has already offered them a default role.

It means there will be only a few determined females who will realize their dreams and only a few women taking part in multiple elements of public life, whether it’s politics, business or academia. In the long term, this will have critical consequences for national development, especially in countries such as Indonesia, which is developing and defining its identity.

While the government could push for equal pay or more incentives for girls to continue on to secondary schooling, businesses and civil society organizations need to lead the advocacy toward a shift in cultural expectations of women. With that, we hope to see more confident girls in classrooms, voicing out their opinions – because there should be no limit to what they can become.

Have you read?

What is ASEAN? An explainer

Why women hold the key to Asia's economic success

Read more from our ASEAN blog series

The World Economic Forum on ASEAN is taking place in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from 1 to 2 June.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Education and SkillsSee all

Lucia Fry and Naomi Nyamweya

April 17, 2025

Jarah Euston and Isabelle Leliaert

April 10, 2025

Kiva Allgood and Sue Ellspermann

April 9, 2025

Sue Duke

April 4, 2025

David Alexandru Timis

March 31, 2025

Utkarsh Amitabh and Ali Ansari

March 28, 2025