The refugee crisis you’ve never heard of – and why it’s about to get worse

Kenya has said it will close the world’s largest and oldest refugee camp

Image: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

Stay up to date:

Migration

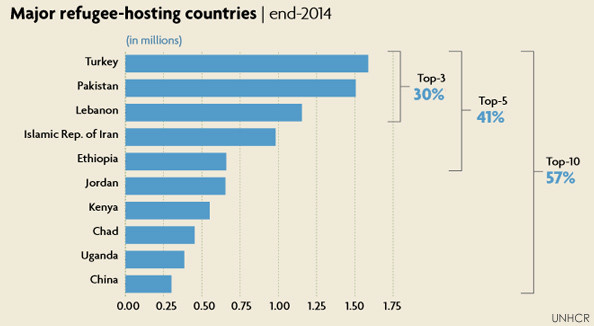

For a long time, Kenya has been one of the most generous refugee-hosting countries, taking in hundreds of thousands of people fleeing war and instability. Now, that looks set to change.

“For reasons of national security, against a pervasive and persistent terrorist threat, Kenya is to close its two largest refugee camps,” the country’s minister for national security, Karanja Kibicho, wrote in the Independent.

It's not the first time the country has made such threats, but that doesn’t make the recent statement any less worrying. Between them, the two camps – Dadaab and Kakuma – are home to more than 600,000 refugees. If they close, it’s not clear what will happen to those living there.

It has in the past been described as the forgotten crisis. But if Kenya follows through with its plans, it could soon be making headlines everywhere.

Inside the world’s oldest and largest refugee camp

In the beginning, the camp was meant to be a temporary sanctuary for those fleeing Somalia’s civil war. “The original intention was for the three Dadaab camps to host up to 90,000 people,” Andrej Mahecic of UNHCR explains.

Twenty-five years on, and Dadaab is the world’s oldest and largest refugee camp, with a population of over 300,000. That puts it up there with cities the size of New Orleans in the US, Cardiff in the UK and Venice in Italy.

A range of services have popped up to cater to the thousands of residents. Dadaab has schools, restaurants and beauty salons. But it’s a precarious existence, even for those with nothing else to compare it with.

“I was born here. I know only this camp,” Mohammed Abdi Abdulahi told the BBC. “I wanted a better life than this one … We are like birds in a cage.”

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

A range of restrictions make life difficult for those who call Dadaab home. Permanent structures are banned, stringent rules limit travel in and out of the camp, and refugees cannot legally work in Kenya. Even if they could, education levels would make it tough for many to find work: in 2015, just 13% of the camp’s adolescents went to secondary school.

In recent years, camp life has been deteriorating even more. For example, a 2011 study from UNHCR and the Danish Refugee Council found evidence of increasing violence, rape and petty crimes. According to reports, the security forces sent to protect refugees do little to help – and have even been caught attacking residents and looting homes.

But as uncertain as their lives are now, things could get a lot worse if the Kenyan government follows through on its promise to close the camps.

Understanding Kenya’s decision

The government’s official line will be familiar to anyone who has followed other migrant crises: refugees are a financial burden and pose a security threat.

“The Kenyan government’s most pressing constitutional and moral responsibility is to ensure the security of its citizens from the risk of violent attack. Our intelligence and security forces have known for a long time that these camps are a dire threat to our people’s security,” Kibicho wrote in his article.

There is little evidence to merit these security concerns. In fact, as Rod Volway, CARE’s director of refugee operations in Kenya, told us, many of these refugees are attempting to escape the same thing: “It is sadly ironic that refugees face these stereotypes when they themselves are fleeing terror. Nobody chooses to become a refugee.”

But while the allegations of terrorist activity might not be accurate, Kenya’s concerns cannot simply be dismissed, says Alasan Senghore, an aid worker who spent many years in the camps with the International Federation of Red Cross.

To be sure, the country has a duty to help those in need of protection – a duty it has so far carried out faithfully: “Kenya’s role as host has been vital in preventing a humanitarian disaster,” Senghore says. That role, though, has not been without consequences. “Kenya has had to bear both the economic and security burden” while the rest of the world has turned a blind eye.

“If you compare this situation with all the investment and discussions around the refugee crisis in Europe, you understand why this is becoming a concern. The refugee camps are one of those forgotten humanitarian situations,” Senghore notes.

A forgotten crisis for everyone except Kenya, which now seems determined to get it back on the international agenda – even if that means leaving more than 600,000 people with nowhere to go.

Living in limbo

The situation in Kenya, while unique, speaks to a wider trend: conflicts might be less intense than in the past, but they are dragging on longer. As a recent Forum report noted, “fragility is the new normal”.

And yet the way the international community responds to them has not changed. Donors tend to focus on high-profile emergency situations while forgetting drawn-out crises. In 2013, for example, the British public donated $20 million in the first 24 hours after Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines. That same year, UNHCR received just $36.5 million to support its operations in Dadaab – far short of the $145 million it required.

Whether or not Kenya follows through on its threat to close the camps, the situation highlights the need to rethink how we handle this “new normal”.

“We need to look seriously at the nature of protracted refugee situations, develop longer-term solutions to making refugees’ lives more bearable – including providing skills training, jobs, education and other opportunities – and find the political will to end the conflicts that prevent safe and voluntary return,” Volway says. “Twenty-five years is too long for generations to live in limbo.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Benjamin Denis and Justine Roche

April 30, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Shoko Noda

April 23, 2025

Daniel Mahadzir and Natasha Tai

March 21, 2025

Robert Muggah

March 10, 2025