The humanitarian system is not working – so how can we fix it?

Image: REUTERS/Ahmed Jadallah

Stay up to date:

Humanitarian Action

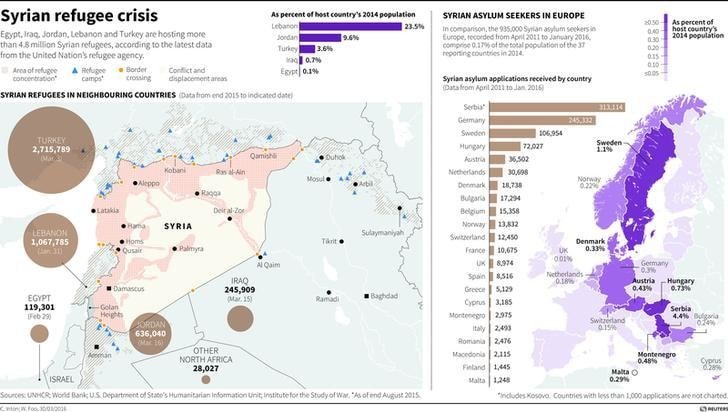

Today, right now, more than 60 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes, most of them in the Middle East. By 2030, fragile states will be home to 67% of individuals who live in extreme poverty. These conditions threaten the world’s population and prosperity in both the near- and long-term.

It should be no surprise that Bono has recently called for a “Marshall Plan” that like its 1947 namesake would deliver “trade and development in service of security—in places where institutions [are] broken and hope [has] been lost.” Nor should it be a surprise that the United Nations has spent the last three years preparing for its first Humanitarian Summit.

Such laudable efforts, however, seem to be based on three assumptions:

- The international humanitarian response system is working;

- Humanitarianism—defined broadly as relief (near-term) and development (long-term)—is apolitical and neutral, and;

- The resulting focus of the response system is on symptoms, e.g., refugees, not geo-political and spiritual, root causes.

The world, and especially those afflicted, are not well-served by these assumptions.

The humanitarian system is not working

Reflecting on the increase in those displaced per day—from 11,000 a day in 2010 to 42,000 in 2014— the recently retired UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), António Guterres, said: “The global humanitarian community is not broken—as a whole they are more effective than ever before. But we are financially broke.”

To be sure, there are tremendous people working at the U.N. and among the international NGOs: but, the above sentiment assumes that all that is needed is more money. And raising money for complex, man-made crises, after all, is simply more difficult than raising money for natural disasters.

Take the example of World Vision (U.S.). It raised $68 million in six weeks for the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and $8 million in two weeks for Nepal’s 2015 earthquake. But World Vision only raised $2.7 million during the first four years of the war in Syria, and only $1.4 million during the first four years of South Sudan’s independence.

But what if our times demand more than more money? What if the real need is not money but a new mindset and method, with new partnerships among investors and implementers?

Aid is not apolitical

Ronald Reagan famously said that a “hungry child has no politics.” True that: but, the child’s food does.

The means by which the afflicted are helped can create their own political dynamics; especially in (post-) conflict zones. If these dynamics are not accounted for—as I argued 20 years ago in my book on humanitarian interventions—then the possibility of unintended, negative, consequences are much worse (despite good intentions).

Meanwhile, it is simply true that if conditions are addressed at the point of origin, then the world is less likely to have more refugees. For example, my organization has developed a strategy to help rescue, restore and return those persecuted by ISIS to the homes they fled, always working through local partners.

The strategy intentionally seeks to build trust and embody reconciliation as it moves toward “return”—where it takes the “political” position of advocating for a “Safe Haven” as a small but strategic step that anticipates longer-term solutions (for more on this approach, see my forthcoming article about a responsible American engagement of the Middle East).

Many in the humanitarian community, however, maintain the traditional position that humanitarian action can be apolitical and impartial. For example, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)—one of the world’s most respected humanitarian organizations, particularly in conflict zones—just announced that it would not attend the Humanitarian Summit.

MSF alleges the summit ... threatens to “dissolve humanitarian assistance into wider development, peacebuilding and political agendas”... A former senior MSF staffer said: “You can ask firefighters to put out a fire [relief]. Don't ask them to build affordable housing [development].”

This perspective begs the question: if the world is experiencing the most forcibly displaced people since World War II; if the source of that displacement is usually conflict; if the overwhelming majority of those living in extreme poverty by 2030 will live in fragile and/or failing states where conflict is endemic; and, if the humanitarian system is not working properly, in part, because it remains unreformed, unable to address root causes; then, shouldn’t we begin to expect policies, programmes, and above all, practitioners with a mindset and method who have been trained to put out fires, build affordable housing, while working in both phases to build sufficient capacity to live side-by-side?

Such thinking requires not only a conceptual reconciliation between relief and development (while respecting the discrete functions of each), but the education, training and resulting capacity to explicitly and implicitly integrate reconciliation into every element of relief and development.

In today’s broken world, every relief decision is a development decision is a reconciliation decision.

As World Vision (U.S.) President Rich Stearns noted last June: “How do you explain to a little boy or girl that we don’t want to help you because the politics of your country is too complex?”

It’s time to address root causes

Twenty-five years ago, in April 1991, the American president George Bush decided to create a safe haven for the Kurds. They had fled Saddam Hussein’s second genocide attempt against them. But a strategy was needed to convince and enable the Kurds to come out of the mountains along the Iraqi-Turkish border, back to the cities of northern Iraq.

My humanitarian intervention book reveals three key lessons from this case: 1) there was the political will to defend a secure area; 2) the area was, in fact, made secure; and, most importantly, 3) an intentional strategy linked relief with development (from transition camps in Zakho to the inclusion of Dohuk in the security zone.

In August 2014, another American president drew a “red line” around Kurdistan, as American air strikes prevented ISIS from taking the Kurdish capital, Erbil. This time, however, 1.8 million people—of different ethnic and/or religious identity—poured into Kurdistan, fleeing ISIS.

I have visited Kurdistan seven times in the last 19 months, visiting leaders at every level, from every type of organization and government agency, while sitting and crying with refugees across the region. Five elements differentiate this crisis from the 1991 crisis, characterizing the complexity in which humanitarian aid is rendered today:

- There has been little political leadership from the international community vis-à-vis ISIS, leaving a conceptually broken and financially broke international humanitarian system to apply relief band-aids amidst little thought of the long-term;

- Leaders at all levels are tired of the hand-out and want an hand-up, seeking entrepreneurial solutions that provide jobs (and with them, justice and dignity);

- The disease of distrust between and among different ethnic and religious groups is profound, and has been largely ignored;

- Trauma, moral injury, and gender-based violence, impacts almost everyone, from the Muslims, Yazidis and Christians (and others) that fled ISIS, to the Kurds themselves, who were long traumatized by Saddam Hussein; and,

- Faith communities and faith-based organizations are theoretically well-positioned to speak to the issues of trust and trauma as a function of the “Golden Rule,” and/or their reconciliation DNA, inherent to most traditions.

These factors demand a different approach, if there is to be any hope of achieving stability, security and therefore prosperity among well-educated Kurds and refugees. As Bayan Sami Abdul Rahman, the Kurdish government’s representative in Washington, D.C., said to me last year: “We are all thinking of the ‘day-after’ ISIS: we are all going to have to live together again.”

Last month, the Kurdish government and my organization co-convened a discussion on “Coexistence, Stability & Reconciliation”. The Kurdish Foreign Minister, Falah Mustafa Bakir, summed it all up succinctly: “There is no future in Iraq for anyone if they seek revenge and not reconciliation.”

In other words—while very different groups are near one another in Kurdistan, waiting on the defeat of ISIS in order to return to their home, or to be protected in a safe haven—now is the time for good research and innovative humanitarian and business programmes that are practical and promote reconciliation.

These programmes would bring together people who would not otherwise meet—from different ethnic and faith traditions—on a regular basis. Critically, these programmes would, generally speaking, not bring people together to “do” reconciliation. They would bring them together according to the self-interest of each. For example, whether individuals were participating in a trauma care programme or learning a new job—two things high on everyone’s list—there would be an opportunity for them to be in contact with someone who would not normally be part of their group.

Such contact, over time and facilitated properly, would provide the previously non-existent possibility of dialogue; and therefore for relationships and trust. Reconciliation must be sewn into the fabrics of society and state—now—if there is to be any chance of enduring peace after the defeat of ISIS.

Such an approach stems the flow of refugees to Europe. It also provides hope as people begin to heal internally while learning how to engage others externally. It is these people that will form the foundation for the future in a post-ISIS region.

Only whole people build whole societies.

Three questions remain

In the World Humanitarian Summit promotional video, several celebrities name the stakes while encouraging support. Only Forest Whitaker, however, talks about reconciliation, saying that the Summit is an opportunity “to resolve conflict through dialogue and reconciliation rather than violence and revenge.”

Three questions remain, however:

- Does the international humanitarian community want to operate outside its comfort zone—that is, will it integrate reconciliation into its relief/development efforts to address the geo-political and spiritual root causes—in order to operate in a conflict zone that is causing a refugee crisis now, and will be home to 67% of people living in extreme poverty by 2030?

- Do faith communities—from local traditions to international organizations—want to embrace the Golden Rule at the heart of their respective identities (while simultaneously recognizing and respecting irreconcilable theological differences), and will they be unafraid to think through and advocate for geo-political solutions?

- Do businesses want to pursue profit with purpose, revenue with reconciliation, investing their innovation in a different kind of “emerging” market?

Positive answers to these three questions might encourage our politicians to become leaders as, together, we re-imagine the practical partnerships necessary to render humanitarian aid in a sustainable way.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Shoko Noda

April 23, 2025

Daniel Mahadzir and Natasha Tai

March 21, 2025

Robert Muggah

March 10, 2025

Sebastian Petric

February 21, 2025