Fingerprint scans could save 5 million children’s lives

“It could save 5 million lives." Image: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

Every day 353,000 children are born around the world, a majority of them in developing countries where a lack of proper record-keeping results in a lack of proper health care. By the age of five, more than 5 million children per year lose their lives to vaccine-preventable diseases.

A new paper suggests thumbprint scans could go a long way to saving them.

Digital scans of a young child’s fingerprint can be correctly recognized one year later. In particular, researchers showed they can correctly identify children 6 months old over 99 percent of the time based on their two thumbprints. A child could then be identified at each medical visit by a simple fingerprint scan, allowing them to get proper medical care such as life-saving immunizations or food supplements.

“Despite efforts of international health organizations and NGOs, children are still dying because it’s been believed that it wasn’t possible to use body traits such as fingerprints to identify children. We’ve just proven it is possible,” says Anil Jain, professor of computer science and engineering at Michigan State University.

“As the technology further evolves, there are many social good applications for this new technique with far-reaching impacts on a global scale. At a touch of a finger, health care workers could have access to a child’s medical history. Whether in a developing nation, refugee camp, homeless shelter or, heaven forbid, a kidnapping situation, a child’s identity could be verified if they had their fingerprint scanned at birth and included in a registry.”

One such application is saving lives by tracking vaccination records. Vaccination records are traditionally kept on paper charts, but paper is easily lost or destroyed. Fingerprints are forever, and, once captured in a database, could be accessed by medical professionals to reliably record immunization schedules and other medical information.

In additional to medical histories, capturing a child’s fingerprint could also be used for the following:

National Identification: Many countries have some form of national identification system, such as the Unique Identification Authority of India, which enrolls any resident over 5 years old using biometric identifiers. With approximately 25 million births each year, India would like to lower the enrollment age. Capturing a baby’s fingerprints at age 6 months or older would assist them in this process and ensure proper identification from an early age.

Lifetime Identities: A digital fingerprint identity system will give children an identity for a lifetime to help combat children and at-risk adults from human trafficking, refugee crisis situations, kidnappings or lack of basic services.

Improving nutrition: In the least-developed countries, where 14 percent suffer from undernutrition, tracking children can help aid initiatives for providing and improving nutrition services and food.

“The impact of child fingerprinting will be enormous in improving lives of the disadvantaged,” says Sandeep Ahuja, CEO of Operation ASHA, an NGO dedicated to bringing tuberculosis treatment and health services to India.

“It could save 5 million lives just by ensuring implementation of well-known measures immediately after birth, like breast feeding, by tracking interaction of health workers, and newborns in underdeveloped countries.”

The study took place at Saran Ashram hospital in Dayalbagh, India, where fingerprints of 309 children between the age of 0-5 years were collected over the course of one year. The fingerprint data was processed to show that state-of-the-art fingerprint capture and recognition technology offers a viable solution for recognizing children enrolled at age 6 months or older.

“Given these encouraging results, we plan to continue the longitudinal study by capturing fingerprints of the same subjects annually for four more years,” Jain says. “This will allow us to better evaluate the use of fingerprints for providing lifelong identity.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the work, which was performed in collaboration with the Saran Ashram hospital, Dayalbagh, India; the Dayalbagh Educational Institute; and NEC Corp., Japan.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

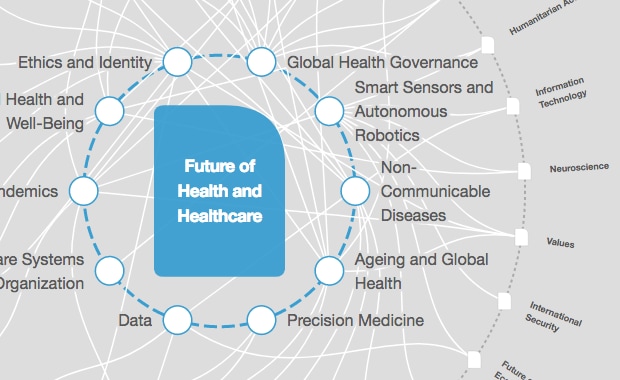

Health and Healthcare

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.