Wealth can make us selfish and stingy. Two psychologists explain why

Image: REUTERS/Stephane Mahe

Stay up to date:

Values

For many, wealth may seem like an unmitigated good – the more of it you have, the better. After all, wealth brings all sorts of advantages, like improved health, greater freedom and control over your life, nicer things, respect from your friends and peers. Yet new research suggests that wealth may also come with certain costs, and impact our social interactions in ways that we overlook.

Life for the poor can be challenging: fewer resources to meet basic needs, more instability in one’s home and work life, and more threatening living environments. For this reason, you might assume that people in the lower social classes would be more self-interested and less likely to consider the needs of others than wealthier individuals, who can afford to be nice.

But a growing body of findings suggests the opposite – that it is those with fewer resources who attend more to the needs of others. For example, one of our studies found that people driving the oldest, cheapest cars were more likely to stop for an experimenter that was waiting to cross the street at a crosswalk. Those with the means to drive nicer cars were more likely to blow right through without stopping.

This may reflect basic differences in how much the rich and poor attend to the needs of others around them. Whereas wealthy folk can rely on their money when times get tough, the poor are more dependent on others and invest more in their relationships.

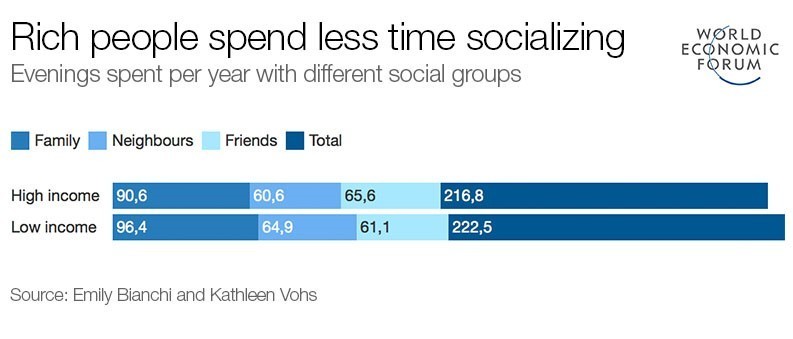

Data show that lower-income individuals spend more of their time socializing with other people than their more well-to-do counterparts, who spend more time alone.

In observed interactions with strangers, working class people are more engaged and friendly; they are more likely to make eye contact or nod while their partner is talking. During the same interactions, middle class people appear ruder, more distracted, checking their cell phones or doodling on a piece of paper.

People from lower social strata also tend to feel more emotionally connected to other people. For example, students in one laboratory study interacted with another participant in a stressful mock-interview situation. Participants from lower-income backgrounds felt more compassion for the other person than did those from higher-income backgrounds. In another study, participants of lower socioeconomic status were better able to accurately infer others’ emotions – they were, in other words, more empathetic.

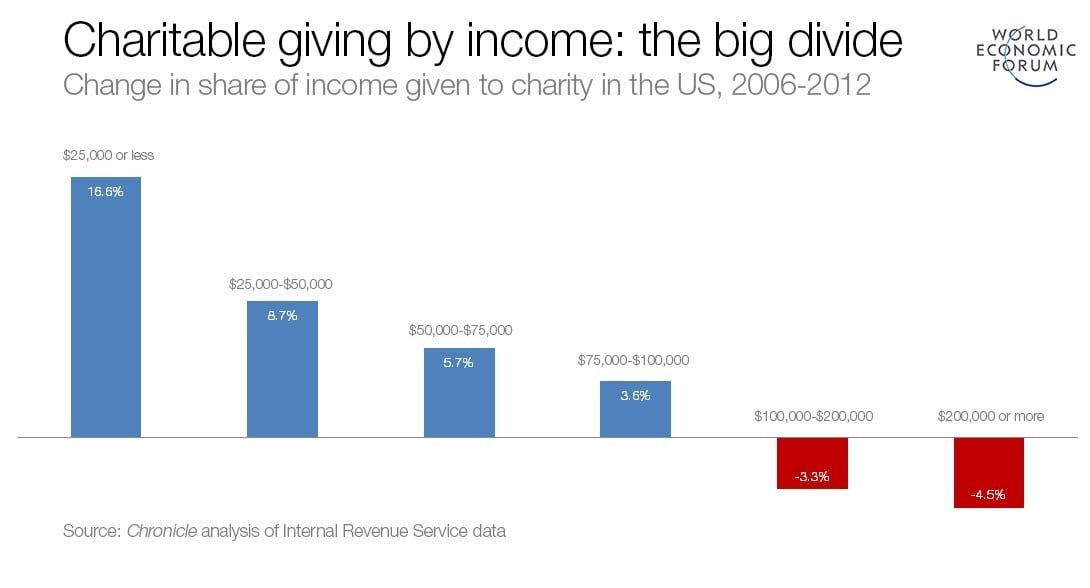

Wealth differences in attentiveness to others may help explain what some researchers have termed the “giving gap”: those with fewer resources are often found to be more generous, a trend that seems to have increased over time.

In surveys of charitable giving all across the United States, lower-income households give a higher percentage of their income to charity than middle-income households. Similarly, lab studies find that adults – and even children – of lower socioeconomic status share more of a valued good (like points redeemable for cash, or tokens exchangeable for prizes) with anonymous strangers.

Whereas wealthier individuals tend to feel entitled to and deserving of more than others – for instance, we find that they are more likely to agree with the statement, “If I were on the Titanic, I would deserve to be on the first lifeboat!” – poorer individuals share more of their limited resources.

Wealth is also associated with tendencies to act in unethical ways. In studies of shoplifting, it is the higher-income, better-educated participants who are more likely to have committed an act of theft. And tax data from the Internal Revenue Service indicate that wealthier people cheat on their taxes more often than those with lower incomes.

In research conducted in our lab, we took a close look at ethical conduct among society’s haves and have-nots. In one study, participants played a computer game to roll dice in what was supposedly a game of luck. Participants recorded their own scores, which ostensibly determined their chances of winning some cash. After five apparently random rolls of a computer die, wealthier participants were more likely to report scores higher than 12 – even though the game was rigged so that scores higher than 12 were impossible. Moreover, we found that wealthier participants expressed the conviction that greed is moral, and it was their greed-is-good attitudes that gave rise to their unethical behaviour.

In another experiment, we tested whether making people feel relatively richer or poorer, by altering whether they compared themselves to someone who is better or worse off than they are, would trigger differences in immoral behaviour. People who were made to feel somewhat richer (by comparing themselves to someone at the bottom of the social ladder) endorsed more unethical decisions, like stealing office supplies from one’s place of work, and even took more candy from a jar that was ostensibly for children. In essence, feeling wealthier – irrespective of how wealthy you actually are – can cause more greedy behaviour.

In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement swept the United States, igniting protests against economic inequality and denunciation of the wealthy as entitled, greedy and immoral. Consistent with these accusations, the research we have described finds that upper-class individuals feel more entitled, are less concerned with the needs of others, and at times behave selfishly, even unethically, to get ahead. For this reason, some degree of anger towards the rich is understandable, particularly amidst a climate of ever-mounting economic inequality.

However, greater self-interest among the wealthy may have more to do with the psychological effects of economic inequality than with some innate characteristic of the rich. Recall that in our studies, when we make people feel wealthier than others, even those who are poor in real life begin to act more selfishly. In essence, when people engage in favourable downward social comparisons – the kind that make you feel better off than others – they tend to acquire the belief they are better than others, more important and more deserving.

New research on how economic inequality affects generosity among the wealthy supports this idea. In states where inequality was high or when inequality was experimentally portrayed as high (making relative differences in wealth more salient), higher-income individuals tended to act less generously than poorer people – just like the earlier findings we reviewed. However, in more equal states or when economic inequality was portrayed as low (that is, when relative differences were less salient), wealthier people became just as generous as everyone else. In other words, under conditions of greater economic equality, the wealthy are less likely to feel disconnected from and superior to others, and are more likely to behave generously with their resources.

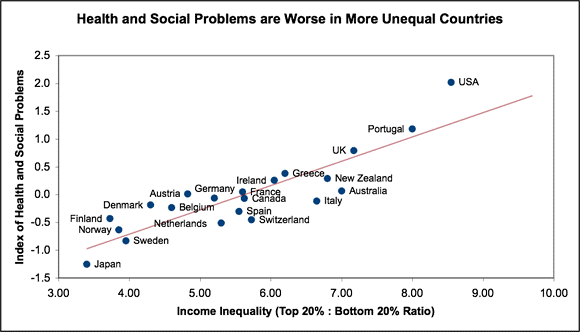

Economic inequality is linked to a host of well-documented and pervasive social ills: shorter life expectancy, higher infant mortality, lower happiness, greater crime, and reduced social trust, among others.

Partly for these reasons, President Obama recently called economic inequality and the lack of upward mobility as the defining challenge of our time. Working to reduce economic inequality, for example by ensuring that all have access to a quality education, expanding the availability of good health care, or making income tax structures more progressive, would almost certainly have a number of positive social benefits, for all of us.

It would help ensure that every individual in society has an equal opportunity to succeed, enhance feelings of social closeness and connection, and even encourage those who are the most privileged and powerful in society to take on the needs of others, their groups, and collectives as their own.

Have you read?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

John Letzing

July 3, 2025

Madeleine North

July 3, 2025

Erik Crouch

July 1, 2025

Stephanie Holmes, Pooja Chhabria and John Letzing

June 26, 2025

Chris Hamill-Stewart

June 25, 2025