Does Europe contribute enough to NATO? The truth about defence spending

America accuses, Europe defends

Image: Todd Diemer

Stay up to date:

United States

For some time, American government officials, defence secretaries and even presidents have accused Europe of “free riding” on the United States for their security.

Germany, the largest economy in the European Union, has come in for particular criticism for its relatively cautious defence budget, and as Angela Merkel pays her first visit to President Trump on Friday, many will be looking to see whether the Chancellor will convince her main ally that leading European nations are serious about paying their fair share.

Germany’s Wolfgang Ischinger, Chairman of the Munich Security Conference, said that sharing the defence burden has become central. But there is an election due in Germany, and Merkel’s opponent Martin Schulz is insisting that there be no “arms race” at the behest of the Americans.

No one can tell whether this tension has the potential to undermine the transatlantic relationship, but judging from the latest figures there are signs that Europeans are taking steps to invest more in their security. EU foreign and defence ministers recently agreed to set up a new “military planning and conduct capability”, which some already remark as progress towards a European military headquarters.

How much are Europeans really contributing to security, and why does it matter?

The context

For years now, average global defence spending has risen, but in spite of all the talk of rising threats in its neighbourhood, most European nations have been bucking this trend. While China, Russia and Saudi Arabia upgraded their defence sectors on an unprecedented scale, EU member states have decreased military spending by nearly 12% in real terms, according to an EU Commission report.

China is estimated to be making a 7% increase in its military spending this year. In the US, President Donald Trump has just asked Congress to agree to boost military spending by around 10%.

European spending is starting to tick up, but will it be too little too late?

Sharing the NATO burden

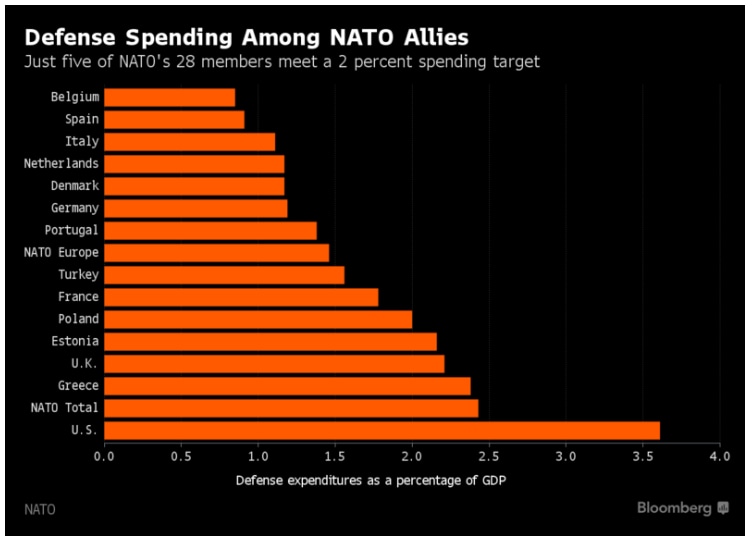

In 2006, NATO allies agreed to spend 2% of GDP on defence. A decade later, only four of the European allies meet that target.

Despite the fact that the allies all re-committed at the 2014 NATO summit to reaching the 2% target within a decade, the long-term spending plans of nations below the line still do not align with that goal.

So how much does the United States pay?

In terms of the NATO common budget (such as salaries, a few common assets, some air defence, command and control systems) the US contribution is in the lead at just over 22%, followed by Germany at around 14%, and France at around 11%.

Why is that so much lower than the 70% figure that we sometimes see? The much more impressive percentage comes from comparing the sum total of US defence spending compared with that of other, smaller allies. It's not really equivalent: a sizeable proportion of global US military capacity is committed to areas outside the North Atlantic zone covered by NATO. The US has nearly 100,000 people serving in the Asia Pacific, for example.

It seems that the way we choose to measure relative contributions will support different conclusions.

Lies, damn lies and statistics

Although the 2% benchmark may serve as a simple indication of political commitment and alliance solidarity, there are a few reasons not to be satisfied with this metric.

For one thing, it does not work well in comparison. A dollar spent on defence in Europe does not go as far as it might in other cases, so purchasing-power difference also has to be considered when making comparisons with a country like China.

Another point of difference is to do with the scope of strategic commitments – unlike Americans, Europeans do not maintain a far-flung network of bases supporting a global alliances system.

However, the main weakness of the 2% metric is that cost does not equal value. Depending on the proportion of a defence budget dedicated to salaries, benefits and pensions, the bulk of spending could go on personnel, and say little about combat power or readiness to deploy and fight away from home borders.

Large but static armies may pass the test in terms of cost, but would fail against numerically smaller forces equipped with superior information technology, faster vehicles and next-generation weapons. The emerging military potential of new technology (e.g. robotics, artificial intelligence) is re-directing attention on how much spending needs to be diverted towards military research and development.

How you spend is as important as what you spend, but it also depends on how you define security.

Same bed, different dreams?

Despite its flaws, the argument about the 2% serves to reveal a possible divergence of perspectives within the transatlantic alliance.

At a NATO defence ministers meeting in February, US Defence Secretary Jim Mattis warned: “America will meet its responsibilities, but if your nations do not want to see America moderate its commitment to the alliance, each of your capitals needs to show its support for our common defence.”

However, anyone expecting the Europeans to simply “cough up” was in for a disappointment. A day or two later, many of the European representatives who had gathered at the annual Munich Security Conference issued their response.

Rather than accepting the need to meet their own commitments to spend more in terms of tanks, planes and soldiers, they highlighted the importance of the contributions European nations make to security besides what is spent on defence. For example, how overseas development spending makes fragile societies resilient against the risks of radicalization and conflict.

Ischinger, the MSC chairman, ended the conference with a proposal for a new metric: the aim to spend 3% of GDP on a combination of crisis prevention, development assistance and defence.

A European point of view

This just serves to highlight the differences in security agendas across the Atlantic. While the US considers cutting diplomacy and aid to fund more military spending, in much of Europe today “security” is understood more in terms of the risks from migration, the socio-economic context of violent extremism, and a need to address root causes by improving regional stability and economic development.

Lastly, European perspectives on security are also being shaped by the way defence policy has become part of the debate on European integration. Ever since the attempts to form a European defence community in the 1950s, dreams of an “autonomous” defence capability accompanied the European integration project.

The notion of strategic autonomy is having a comeback, as shown by its prominence in the latest 2016 EU global strategy. Federica Mogherini, who is in charge of the EU foreign and security policy, insists that the new military headquarters is “not the European army” but some European leaders are saying it is the first step towards exactly that.

Europeans are divided on the threat from Russia, wary of “America first” rhetoric (perhaps wondering if buy American, hire American also extends to the defence sector) and mindful of weak public support for defence spending in an era of low growth. They are looking again at how defence integration offers a way to unite Europe and save money at the same time. For instance, a recent European Commission study found that if member states integrated their procurement of military equipment, they could save up to 100 million euros.

So what can we expect Friday's meeting to tell us? Either Merkel will bow to American demands and put to rest any doubts about Germany’s commitment to NATO, or we may hear the case for efficiency, a broader security concept, and the value of European autonomy through defence integration. It represents a test of leadership, in either case.

Want to know more? Watch this Davos debate: Is the transatlantic at a tipping point?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Geo-Economics and PoliticsSee all

Kate Whiting

August 5, 2025

Spencer Feingold

July 30, 2025

Matt Watters

July 29, 2025

Valeriya Ionan

July 28, 2025

Michael Wang

July 28, 2025

Mark Esposito

July 24, 2025