15-hour weeks, basic income and doughnuts. Are these the big ideas that could end inequality?

Economic growth alone may not be enough to quell public anger about the widening gap between rich and poor.

Image: REUTERS/Mark Blinch

Stay up to date:

Inclusive Growth Framework

At an unusually divisive time for politics in the West, there’s one thing most people can agree on: the economy is not working well enough, for enough people.

Right now, just 1% of the world’s population holds over 35% of all private wealth, more than the bottom 95% combined. According to Oxfam, the eight wealthiest individuals in the world – all men – have the same wealth as 3.6 billion of the world’s poorest. The world could see its first trillionaire in the next 25 years, yet one in nine people go to bed hungry every night and one in 10 of us still earns less than $2 a day.

And while the problem is truly global, it also exists within countries – including some of the world’s most advanced economies. By the late 2000s, income inequality had risen in 17 out of the 22 OECD countries, including by more than 4% in Finland, Germany, Israel, New Zealand, Sweden and the US.

Inequality is, as Jaideep Prabhu, a Professor of Business at Cambridge University, writes, “the defining social, political and economic phenomenon of our time.” The latest Global Risks Report agrees. The report ranked “rising income and wealth disparity” as the most important trend that will shape the world in the next decade.

The rise of anti-establishment populism, as well as concerns about the revolution in robotics and artificial intelligence, suggest that a revival of economic growth alone may not be enough to address the widening gap between rich and poor.

With capitalism in need of fundamental reform, here is a list of some of the bold ideas that could challenge the status quo.

Universal Basic Income

“Consider for a moment that from this day forward, on the first day of every month, around $1,000 is deposited into your bank account – because you are a citizen,” writes the author Scott Santens in this article.

Universal Basic Income, or UBI, is not a new idea (experiments have taken place in the US, Canada, Namibia, India and Brazil, while Finland and the Netherlands plan to follow suit), but this “social security for all”, which would guarantee a starting salary that is above the poverty line for the rest of your life, is experiencing a revival.

“Rising inequality, decades of stagnant wages, the transformation of lifelong careers into sub-hourly tasks … all of these and more are pointing to the need to start permanently guaranteeing everyone at least some income,” says Santens.

While critics argue that a UBI is unaffordable and would encourage people to do nothing, some advocates believe it would help to soften the blow of automation and give us the freedom to do something we really enjoy. “I firmly believe that a Universal Basic Income is the most effective answer to the dilemma of advancing robotization,” argues Dutch economist Rutger Bergman. “Not because robots will take over all the purposeful jobs, but because a basic income would give everybody the chance to do work that is meaningful.”

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Redistribution

We should share more of the world’s wealth, or face the populist consequences. That was one of the over-riding messages from Davos 2017.

Oxfam’s Winnie Byanyima said it was time to “rebalance this unjust economy,” and other high profile voices agreed. “Individuals and societies need to be smart and well organized to emerge as ‘winners’ in a new renaissance,” said Oxford academic Ian Goldin. “They should create social safety nets for the dispossessed” through greater wealth distribution.

Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba and one of China's most successful businessmen, urged countries to avoid the mistakes made by the US, which he said has squandered its wealth on foreign wars instead of investing in infrastructure and education. “You’re supposed to spend money on your own people,” he argued.

In the session Squeezed and Angry: How to Fix the Middle-Class Crisis, Christine Lagarde, chief of the International Monetary Fund who warned Davos participants about the dangers of inequality back in 2013, didn’t mince her words. “It’s an opportune time to put in place the policies we know help,” she said. “When you have a real crisis, what kind of measures do we take to reduce inequality? It probably means more redistribution.”

Wealth redistribution, of course, means higher taxes for higher earners (though some would argue that this would stifle growth), which is what then US Vice-President Joe Biden argued for in Davos. We need to take “common sense” steps, he said, such as “implementing a progressive, equitable tax system where everyone pays their fair share.” He also proposed providing free college education for all.

A 15-hour work week?

Most of us would like to work less, but would forcing us to spend fewer hours at our desks be good for the global economy? Rutger Bregman thinks so.

The world’s major economies are richer than they’ve ever been, yet excessive work and pressure is killing us, he argues in his book, Utopia for Realists.

“As we hurtle through the first decades of the 21st century, our biggest challenges are not too much leisure and boredom, but stress and uncertainty,” he writes in this piece for The Guardian.

If we worked less and cut out pointless jobs, we’d make fewer errors and have time to do the things we enjoy. Furthermore, countries with shorter working weeks consistently top gender-equality rankings, while “countries with the biggest disparities in wealth are precisely those with the longest working weeks.”

Bregman isn’t the only one to call for a shorter working week. James W. Vaupel, from the Max-Planck Odense Institute for Demographic Research, argues that we should only work 25 hours a week (though we should keep this up until we’re 80). “In the 20th century we had a redistribution of wealth. I believe that in this century, the great redistribution will be in terms of working hours,” he said.

Doughnut economics

While growth at all costs has lifted millions out of poverty, it’s also left a lot of people behind and ravaged our environment. Is the solution to be found in … a doughnut?

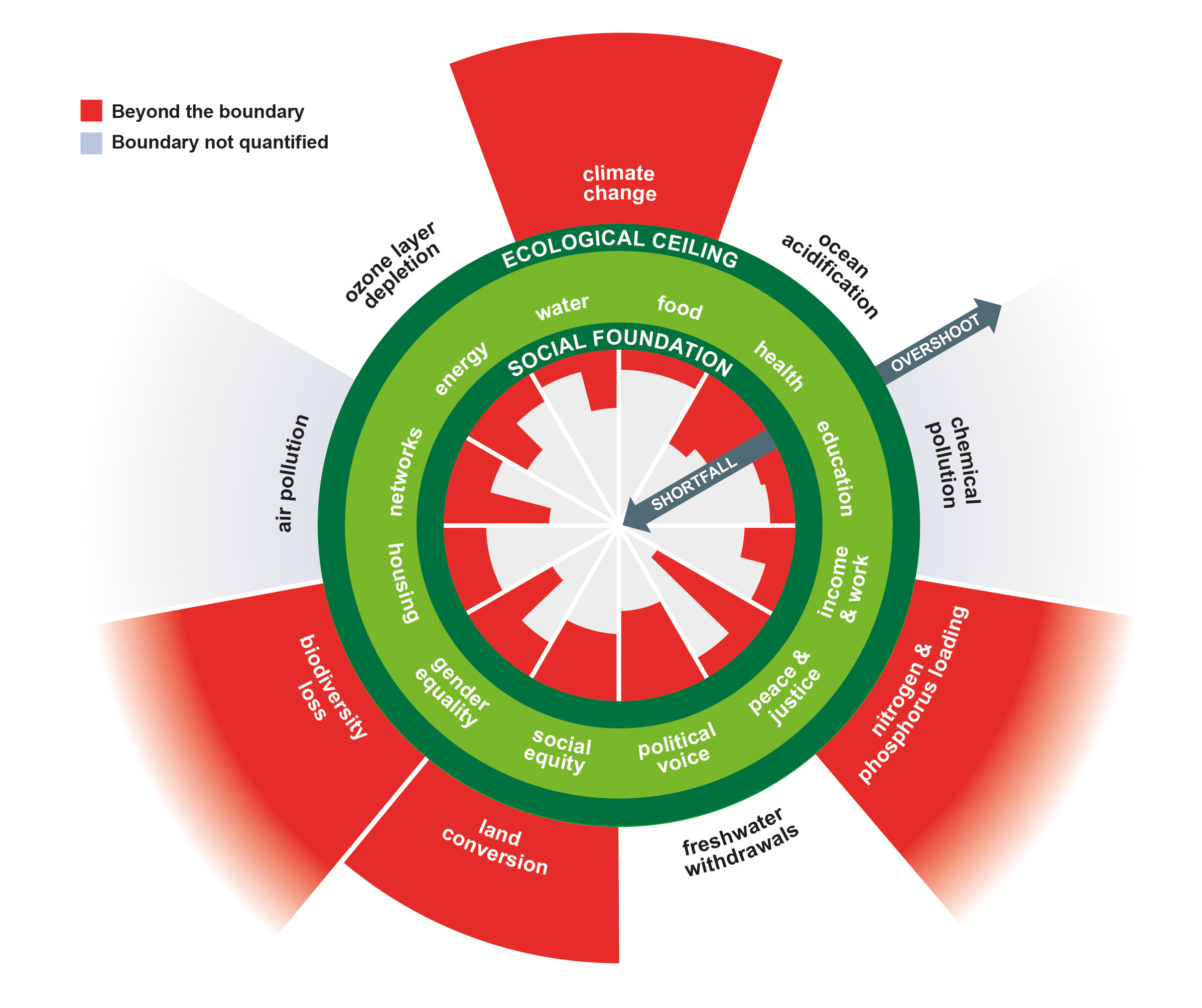

In her book, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Oxford University’s Kate Raworth argues for a radical overhaul of our traditional economic models. What’s the point of a thriving economy if people, and the planet, continue to suffer?

“Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet,” she says. “In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials … while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend.”

Raworth’s “doughnut” is a diagram showing social and planetary boundaries, between which lies an “environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive.” The model “allows us to see the state in which we now find ourselves,” Raworth writes. At the moment, there are billions of people who still live in the hole in the middle, while several of the planetary boundaries have been breached.

The purpose of economics, says Raworth, should be to help us enter that safe space and stay there.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Open borders

Fears over immigration may have played a central role in the Brexit vote and US election, but at a time when the world has more barriers than ever before (three-quarters of all border walls and fences were erected after the year 2000), is there a case for tearing them down?

Closed borders are one of the biggest barriers to global equality, says Bregman. “Just take for example someone who lives in Nigeria and has exactly the same skill set, the same education as someone who lives in the UK or the US, but they earn about eight times less,” he told Business Insider.

“So the right passport is worth a lot of money. It's a huge source of global inequality.”

A World Bank study estimated that if developed countries were to take in just 3% more immigrants, the world’s poor would have over $300 billion more to spend, while there is a huge body of research that shows how carefully managed global migration and ethnic diversity strengthens a country's long-term economy.

“In a world of insane inequality, migration is the most powerful tool around for fighting poverty,” writes Bregman.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Mamta Murthi and Sania Nishtar

June 19, 2025

Julia Hakspiel

June 17, 2025

Swapan Mehra and Akim Daouda

June 16, 2025

Aengus Collins

June 12, 2025

John Letzing

June 11, 2025

Valentina Vellinho Nardin

June 10, 2025