There’s a cure for Latin America’s murder epidemic – and it doesn’t involve more police or prisons

Prisons have done little to reduce the number of violent crimes in Latin America

Image: REUTERS/Daniel Becerril

Stay up to date:

Latin America

San Salvador is confronting a murder epidemic. The city is the world’s murder capital for the second year in a row. The homicide rate reached 136.7 per 100,000 residents in 2016 – at least 17 times the global average. Although registering a decline in murder compared to the previous year, El Salvador’s capital still beat out Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, and San Pedro Sula in Honduras for the world’s top spot.

Salvadorans, Venezuelans and Hondurans are not the only Latin Americans preoccupied by runaway murder rates. Notwithstanding recent improvements in public safety, Colombians still suffer from some of the highest absolute numbers of murder on the planet. Brazil features the planet’s highest homicide toll – almost 60,000 assassinations a year. And at least a third of Central and South Americans know someone who’s been shot dead in the past 12 months.

Across Latin America, death stalks the young. Every 15 minutes a young Latin American – usually a poor young man – is murdered. Latin America has long been the world’s most murderous part of the world, experiencing some 2.5 million homicides since 2000. At least 75% of these were committed with firearms, far above the global average. Paradoxically, violence has worsened despite far-reaching gains in poverty reduction, education, health and overall living standards.

Latin America’s homicides are rising at a time when murder is declining virtually everywhere else. Today, the regional murder rate stands at roughly 22 per 100,000 people: it will increase to 35 per 100,000 by 2030 if trends continue uninterrupted. There is no other region that comes even close to matching these rates.

While most Latin Americans are concerned about rising crime, seven countries stand out: Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Venezuela. Together, they generate one-quarter of all intentional murders around the world each year. An astonishing 44 of the 50 most homicidal countries and 23 of the 25 most murderous cities in the world are currently located in Latin America.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Part of the reason for the persistently high rates of crime in Latin America is that homicides are seldom solved or result in a conviction. In North America and Europe, roughly 80% of all homicides are resolved. Yet in many Latin American countries, the percentage falls to roughly 20%. In Brazil, Colombia, Honduras and Venezuela, less than 10% of murders result in a conviction.

As a result, people’s faith in the policing and criminal justice system has plummeted. In Latin America, life is cheap because the cost of murder is so incredibly low. As people lose faith in law enforcement and the courts, they are more inclined to take justice into their own hands.

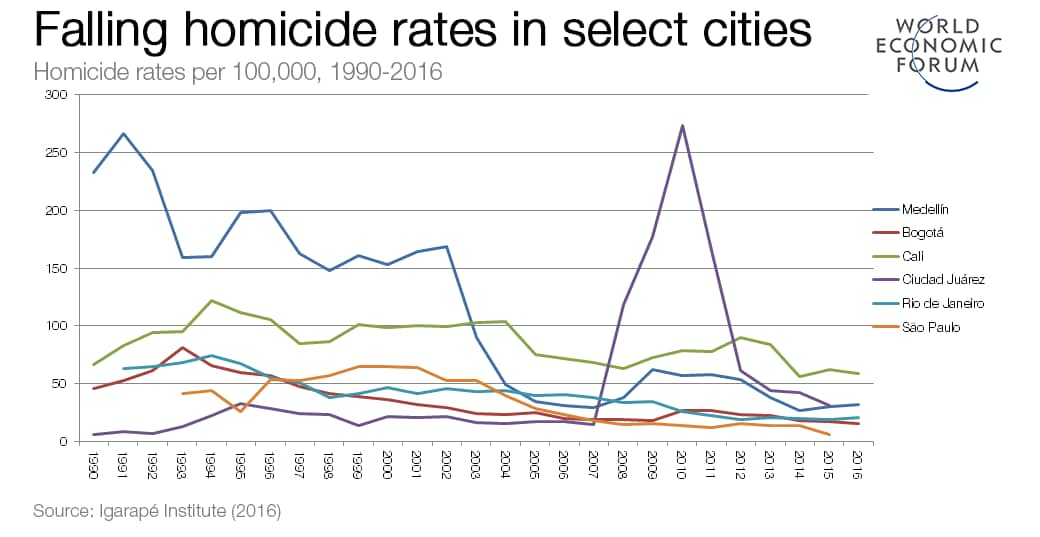

If there’s any good news it is that homicidal violence is not inevitable. There are examples across the region of countries and cities turning things around. Big cities like Bogota, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro saw homicide rates decrease by 70% or more over the past decade.

Civic leaders – especially enlightened mayors – were at the forefront of this revolution. Mayors in Bogota, Cali, and Medellin combined visionary planning and clear targets with hot spot policing and welfare programmes focused on neighbourhoods with high levels of social disorganization and at-risk young people.

Steady declines in murder are not only feasible, they are fundamental. The cost of criminal violence to Latin American economies is far-reaching, amounting to 3.5% of the region’s GDP, or up to $261 billion a year. This translates into roughly $300 per person.

The consequences of unproductive spending on public security and lost productivity associated with premature deaths are dragging back economies that have made real gains since the dark autocratic years of the 1960-80s. High rates of murder are also undermining social capital and social cohesion: there is an unacceptable tolerance for homicide among large swathes of the population.

Put simply, investments in public security across Latin America are inefficient and often focused on all the wrong areas.

How have Latin American governments attempted to deal with this problem so far? Most of them have ploughed more and more money into police forces, the judiciary and prisons. According to a recent study, Latin American governments spent between $55 and $70 billion on public security. That’s on average a third of the amount spent on health and education across the region.

This approach is extremely expensive. Take the example of prisons. Prisons costs are rising because of the expansion of mass incarceration across the region. The prison population rose from 101.2 inmates per 100,000 in 1995 to 218.5 per 100,000 by 2012 – an increase of 116%.

Over the same period expenditures on prisons increased from $4.3 billion in 2010 to $7.8 billion in 2014. Meanwhile the costs of incarceration also increased from roughly $5.8 billion in 2010 to more than $8.4 billion in 2014 – a 45% increase. Taken together, the overall losses are on average $13.8 billion a year to the region, or 0.39% of GDP.

Not only is this approach costly, there´s painfully little evidence that it works. While spending on health and education is positively correlated with improved wellbeing and literacy outcomes in most Latin American countries, we have yet to see similar gains in public security and safety.

What does all this mean? For one, it means that throwing more police and prisons at the problem isn’t working. The status quo is unacceptable and bold solutions are urgently required.

So what if Latin American governments and societies committed to a 50% reduction in homicide over the next decade? This amounts to year-on-year declines of just 7.5%, well within the realm of possibility. The savings would be considerable, starting with roughly 365,000 lives that would otherwise be lost. The material dividends would also be substantial.

Halving homicide is precisely the goal of a new campaign being launched by more than 20 organizations across Latin America. Achieving this goal will require that Latin American governments invest in a few commonsense strategies.

At a minimum, governments, business and civil society groups need to adopt evidence-based strategies and data-driven interventions, focusing on hot spots and hot people. After all, violent crime is often “sticky” and tends to concentrate quite reliably in very specific neighbourhoods, among poorer, less educated and younger people, and at certain times of the day.

Prevention and reduction efforts must also be guided by hard targets that set murder reduction as an explicit goal, not a hopeful by-product. While requiring political courage, the rewards are considerable.

If reductions in murder are to be sustained, a concerted effort is needed to repair tattered police-community relations in the most violence-affected settings. Neighbourhoods exhibiting the highest homicide rates are also typically those registering the lowest trust in the police.

Problem-oriented policing has an especially positive track-record, especially when it comes to tackling gang-related murder and intentional homicide. Improvements in investigation and prosecution of homicides are also central to restoring law and order.

Finally, Latin American governments need to double down on prevention. Age and educational attainment are key factors shaping vulnerability to both perpetrating and being a victim of homicide. Access to – and retention of – sustained income is also an important deterrent to criminal involvement.

In Medellín, a 1% increase in permanent income generates a 0.4% reduction in homicide. Investment in positive early childhood development, parenting skills, youth employment (especially for young offenders), mentorship and life-skills training are cost-effective and have multiple positive impacts.

We know the cure – it’s time for Latin Americans to take the medicine.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Visit the homicide reduction campaign website to learn more about how you can get involved. The campaign – Instinct for Life (Instinto de Vida) – is calling on governments, businesses and civil societies to reduce homicide by 50% in 10 years. More than 20 organizations from across Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Venezuela are on-board, along with the CAF, OAS, IADB and OSF.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Social InnovationSee all

Kerry Breen and Sylvana Quader Sinha

June 20, 2025

Georgina Mondino and Maximiliano Frey

June 18, 2025

Gaurav Ghewade

June 17, 2025

Rya G. Kuewor

May 13, 2025

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025