How satellite surveillance is hauling in illegal fishers

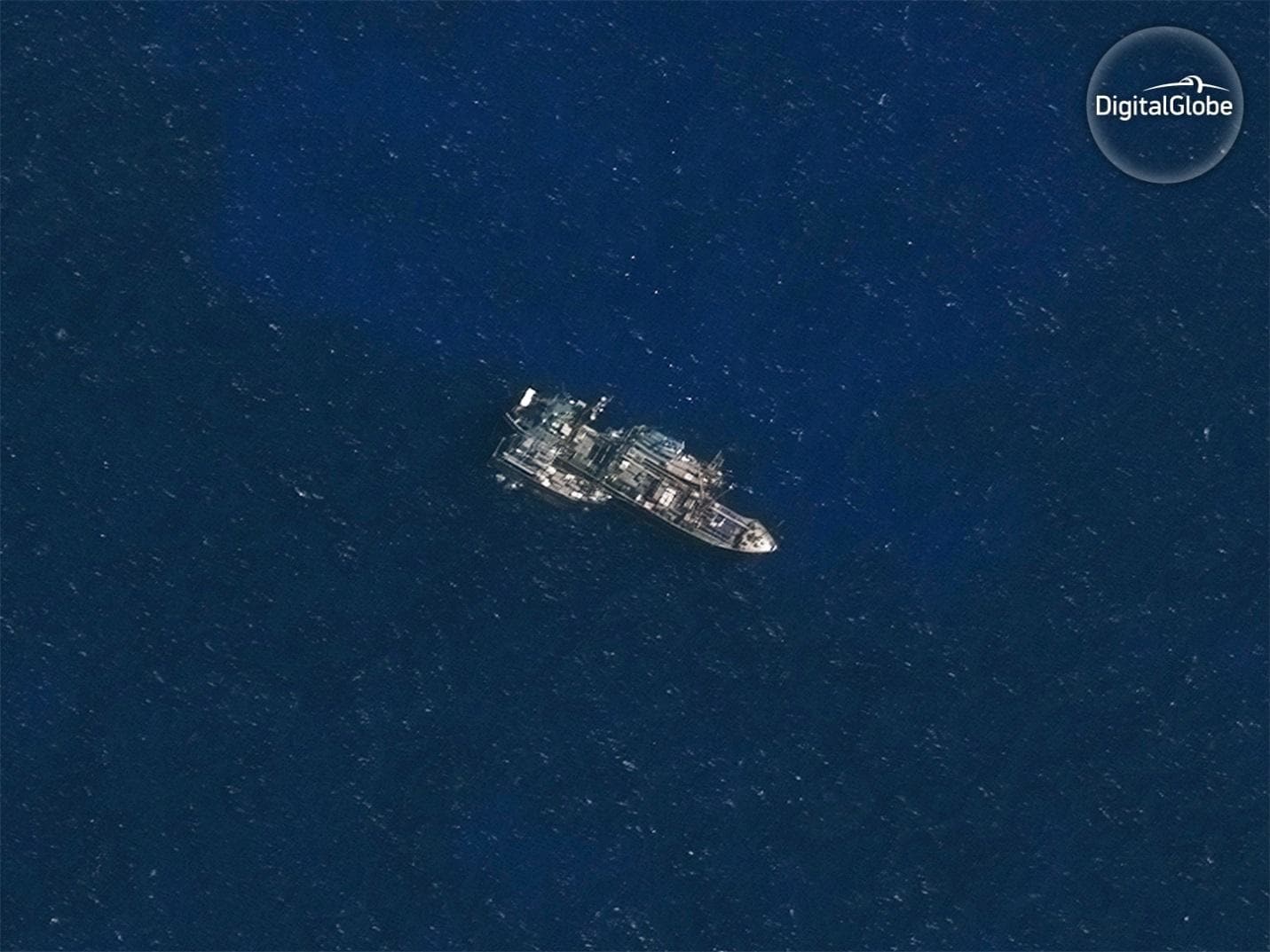

Net results ... satellite imagery provides a bird's-eye view of fishing vessels

Image: REUTERS/Pascal Rossignol

Stay up to date:

Space

There is a huge challenge of illegal fishing, stealing perhaps a fifth of the world’s total legal catch. The humanitarian and environmental costs are well known: plundered oceans, food insecurity, even human trafficking.

What’s not well known is the best way to stop this behaviour – at scale. We need a way to find anomalies in an ocean full of traffic: to red-flag activities worth using a limited number of magnifying glasses to look more closely at.

Together, DigitalGlobe and Planet have those lenses in the sky: a unique vantage point from our perch in space. But identifying behaviour suspicious enough to task them means sifting through the actions of hundreds of thousands of vessels all over the planet, in near-real-time, fast enough to capture the photographic evidence by satellite that can identify illicit activities.

The goal is to spot trans-shipments. That’s when a trawler transfers its illegal catch to a refrigerated cargo ship (a reefer), mixing legal and illegal catches and losing the provenance that allows proper governmental tracking of the fish on board. These hard-to-track trawlers can then resume open-seas fishing without being subject to port-authority scrutiny.

As recently as 2015 it took more than three months of research, behavioural analysis, and satellite vessel tracking to identify just one reefer receiving trans-shipments. In 2016, dedicated reporters even netted the Public Service Pulitzer Prize for their diligence, helped in their investigation by images from DigitalGlobe satellites.

But that kind of analysis couldn’t scale. The reporters' “Look here!” tip couldn’t be automated.

Until now. Now, SkyTruth and Global Fishing Watch (GFW), its partner organization, might be able to change that.

Large, open-seas, commercial vessels, including many fishing trawlers and all of the reefers capable of onboarding illegal catches, are obliged to – but don’t always – continuously transmit a universal Automatic Identification System (AIS) beacon. These public signals were originally mandated to prevent collisions, but new uses are emerging. Especially when those beacons go dark.

The GFW project maps every AIS signal, making visible all fishing activity anywhere in the ocean. In all that data, GFW’s analysts are finding patterns – patterns that suggest trans-shipments in progress, often triggered when a captain turns off the AIS. And recently, GFW is adding machine-learning pattern recognition to scale the analysis. That’s how they can sift through 21 billion signals to highlight only a few thousand suspicious incidents. GFW calls them potential and likely rendezvous.

One dot could represent a rendezvous between smaller fishing boats and AIS-enabled reefers, travelling side-by-side slowly enough to transfer fish. Or a dot could indicate AIS radio silence in an area known for overfishing or poaching. In either case, something worth a closer look. By satellite.

Planet’s fleet of Dove satellites spans the globe, imaging the entire planet every day at high enough resolution to cull the target list even further: Planet’s imagery can locate ships where AIS signals are suspiciously absent, spot ships joined at sea, and track fishing behaviour.

And a confirmation from Planet can send an automated tip to DigitalGlobe, requesting the tasking of one of our highest-resolution satellites to sweep for a bird’s-eye view. That visual scrutiny might identify open cargo holds, transfer cranes, even ship-to-ship mooring lines – actionable evidence for authorities to act on.

By leveraging our unique vantage point from space, and aided by increasingly accurate artificial intelligence to connect the dots at scale, we’re working to tighten the workflow from suspicious signal to real-time proof.

In the satellite community we call it “tipping and cueing” – noticing something interesting and pointing sensors at it. That’s just a mechanical way of saying let’s all watch out for each other. And let’s use the smartest tools on the planet to do it.

Barriers to execution are often barriers of imagination. Of not considering how the models from one industry might be applied on a planetary scale. Let’s not have a failure of imagination imperil our common bounty on the open seas.

The authors are members of the Global Future Council on Space Technologies.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Food and WaterSee all

Jai Shroff

April 22, 2025

Michael Atkinson and Andrea Willige

April 9, 2025

Dipali Khandelwal and Hemlata Chauhan

April 8, 2025