6 ways to align the energy transition with economic growth

These proven policies can help governments harness the winds of change.

Image: Andrea Boldizsar/Unsplash

Stay up to date:

Energy Transition

Coordinated public sector support once kickstarted the technologies, business practices and markets needed for a clean, prosperous and secure low-carbon energy future.

Over time, the increasing profitability of clean energy activity has come to drive exponential growth in global annual investment – amounting to more than $333 billion in 2017 – and local jobs to support the deployment of products and services. Households, businesses and governments are now increasingly seeking these new energy solutions due to the real economic value they can provide.

But the energy transition is still not moving fast enough. And therefore the ball is back in policymakers’ court to accelerate the shift to the clean energy solutions of the future. Countries looking to tap into these solutions’ proven economic and environmental advantages face the new challenge of how to employ the right mix of policies to drive the transition locally, faster and at the lowest cost. As countries like China, India and Mexico demonstrate, the motivation is not just to avoid the costs of global climate change, but increasingly to capture their share of the transition’s economic opportunity for domestic voters and taxpayers – estimated to exceed $1 trillion per year worldwide.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Energy reviewed the existing policy recommendations from leading thinktanks, industry groups and research institutes. Six core policies emerged as consensus across these sources.

1) Integrated policy frameworks. Traditionally segmented energy sectors will in the future need to be deeply integrated, highly electrified energy systems. As a result, governments should frame the long-term direction for the energy sector as a whole and involve key stakeholders at each stage. The result should provide a clear vision for society at large, a firm direction for emerging technologies and a solid incentive for commercial innovation, while also ensuring investor certainty.

2) Carbon pricing. At national and/or subnational levels, pricing carbon through a broad tax or cap-and-trade allowance system will help markets over time find the cheapest ways to reduce emissions by providing a single stable price signal. Sub-state, provincial alignment has proven effective in preventing cross-border “leakages”; the same should be facilitated at regional and global levels.

3) Smart subsidies. Governments should look first to eliminate inefficient and regressive fossil fuels subsidies, which far outweigh those given to clean technologies. Taxpayer-funded subsidies for the energy technologies of the future need careful targeting and should be responsibly allocated through market-based mechanisms, in-kind public private partnerships and transparent public planning processes.

4) Supportive innovation. Governments can remedy historically lacklustre energy research and development funding through in-kind funding programmes and coordinating platforms. “Governments participating in Mission Innovation have pledged to double their clean energy R&D budgets, leading the way in boosting investment in much-needed breakthrough technologies and applications,” says Leonardo Beltrán Rodríguez, the Mexican government’s deputy secretary for planning and energy transition. Governments can also use public tenders to leverage downstream private sector innovation in manufacturing, supply chain and delivery models.

5) Energy efficiency. The least expensive energy is energy that is not used. Across all major energy sectors, from power generation and distribution to industry, transport and buildings, immense opportunities exist for efficiency. Besides incentivising direct investment in efficiency – once estimated to offer 100% return on $500 billion in the US alone – the most effective policies institute clear mandates and standards for appliance, building and vehicle efficiency.

6) Electricity market design. The attributes of increasingly cost-effective electricity generation, storage and use technologies, as well as the rise of IT-enabled rapid interactivity between supply- and demand-side resources, pose new challenges for electricity markets. “As an independent market operator, we believe that optimal approaches are needed for an efficient system that allows the greatest practical level of competition and innovation to ultimately deliver the best results for consumers,” says Audrey Zibelman, CEO of the Australian Energy Market Operator.

Underlying each of these recommendations is evidence of how policies supporting the transition have fared: first, that businesses will mobilize quickly and efficiently in response to smart, supportive and stable policies designed for scale. In developed markets, this entails replacing dirty and inefficient assets with clean, resilient and low-cost ones. In developing countries, those policies can support rapid economic growth that avoids the traps of past industrial models by using new energy technologies and market designs of the future.

Second, where the winds of proven technologies and market designs are at your back as in the energy transition, policy changes that can quickly result in economic growth and commercial competitiveness are less controversial.

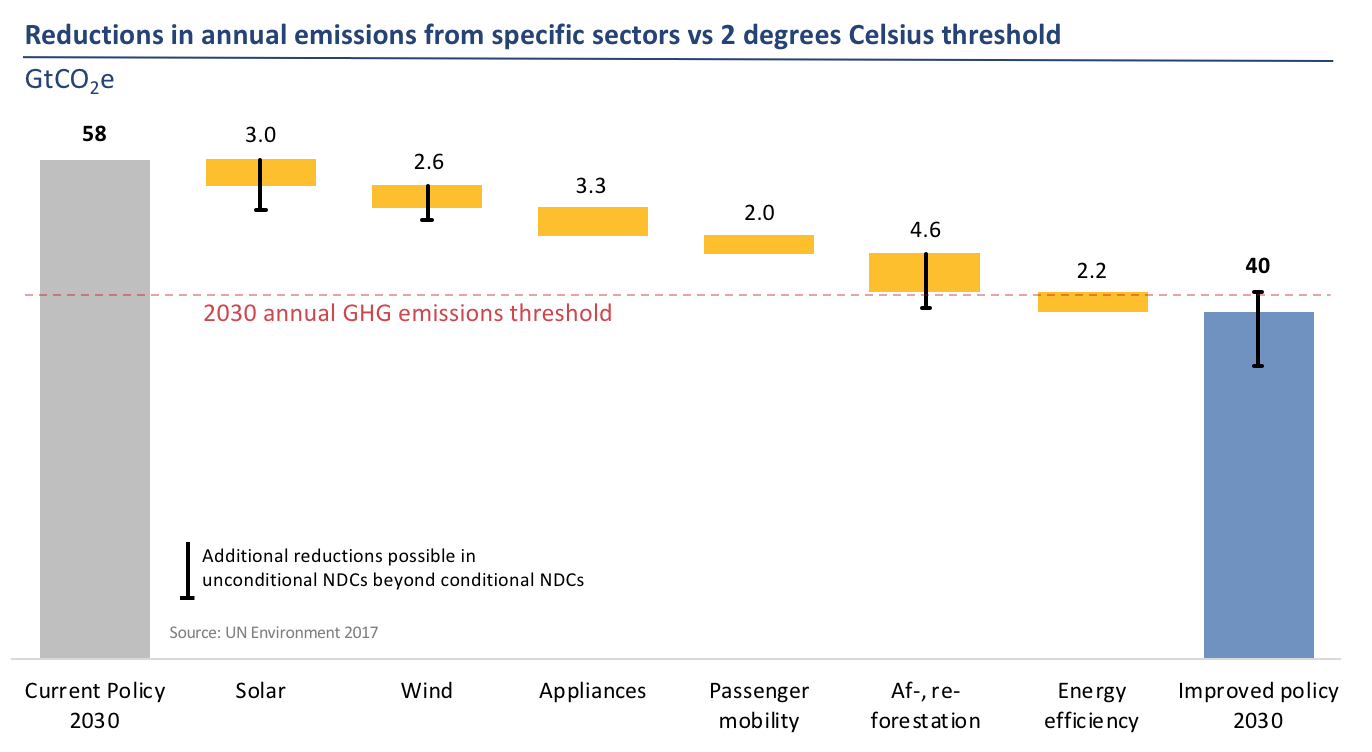

These consensus policies, in addition to others just shy of unanimity, amount to a toolbox for policymakers. They will need it: UN Environment’s 2017 Emissions Gap Report notes that “missing the 2020 options of revising the [nationally determined contributions] would make closing the 2030 emissions gap practically impossible”.

The good news: the policy solutions that have broad consensus can in fact frame and unleash the market activity necessary to reduce annual emissions by 2030 by more than double what is needed to maintain a pathway consistent with 2 degrees, as illustrated below.

These estimates are remarkable for showing that existing technologies and business models, coupled with proven policies from leading country contexts, can bring the world in line with the 2 degrees Celsius goal by 2030.

Clear, consistent and detailed national and subnational policies – beyond goals and commitments – can help bring these solutions to scale. Already, global markets have reduced average wind and solar prices by 47% and 72% respectively over the past eight years. What could we expect if policies opened the gates not only to global but also to local, component manufacturing, supply chains and delivery models?

The few ceilings that do exist on the rapid growth of these solutions are due not to natural resources or lack of ingenuity but to a shortage of political imagination: forward-looking policy can structure market incentives to efficiently continue their growth.

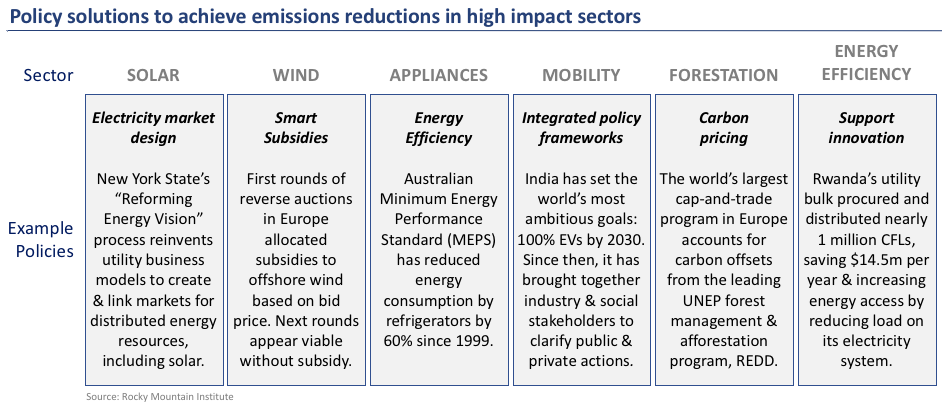

For example, the rise of high-penetration wind and solar without storage or demand flexibility can cause traditional wholesale power markets pricing mechanisms to fail during peak generation hours. Exemplary policy solutions for this challenge and others are illustrated below.

The success of policies such as these, validated by expert consensus, should leave international leaders and regulators with little cause for hesitation. These policies can tap market forces to increase local income, make energy clean and more cost-effective, improve self-sufficiency and strengthen energy security. At the same time, they can create a collective glide path to a lower-risk, low-carbon future.

The trade-off is simple: act now with integrated long-term policies to smooth that path, or necessitate sharp and sudden regulatory shifts in 10-15 years that pose the same threat to economic growth as the climate disaster they hope to address.

“Significant investment from the private sector will continue to be required to support the energy transition,” says Teresa O’Flynn, managing director at BlackRock. “Clean energy policy initiatives will be more successful if they acknowledge the needs of private capital and build the appropriate environment to encourage investment, which includes developing a stable, consistent, transparent long-term policy and regulatory environment.”

The World Economic Forum's Global Future Council on Energy suggests that countries apply this policy toolbox to their own unique contexts, considering both the challenges and opportunities it might create. They may also speed the pace of engagement and learning between their contiguous and regional neighbours, as a cooperative approach can speed domestic progress faster than a go-it-alone attitude.

As a result, countries can arrive at this year’s Facilitative Dialogues and COP26 in 2020 confident in their ability to take near-term climate mitigation to speed economic growth – rather than threaten it.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Energy TransitionSee all

Pascale Junker

May 26, 2025

Roberto Bocca

May 23, 2025

Babajide Oluwase

May 22, 2025

Eleni Kemene and Anne Christianson

May 16, 2025