Our food system is no longer fit for the 21st century. Here are three ways to fix it

For every dollar spent on food, society pays two dollars in health, environmental, and economic costs.

Image: REUTERS/Jean-Paul Pelissier

Stay up to date:

Circular Economy

Food is part of our cultural identity and, at the most basic level, essential to our survival. Over the past 200 years we have seen unprecedented development of agriculture and the global food industry, which now brings many people reliable, affordable access to an extraordinary variety of food. Yet it is becoming increasingly clear that the ways we grow food and process it are undermining our health, and are not fit to meet the needs of a growing global population.

There are no healthy choices in an unhealthy food system. While we are increasingly encouraged to eat more responsibly, we have to acknowledge that the negative health impacts of current food production are mostly unavoidable. Whether you choose an apparently healthy salad or a burger, you are still consuming food that undermines your health and wellbeing.

Today, for every dollar spent on food, society pays two dollars in health, environmental, and economic costs. Surprisingly, these costs – which amount to $5.7 trillion per year globally – equal those related to issues such as obesity, diabetes, and malnutrition. Significant time and effort go into tackling the problems of consumption – and rightly so – but the damage caused by production is just as bad and can no longer be overlooked if we want food that is truly healthy.

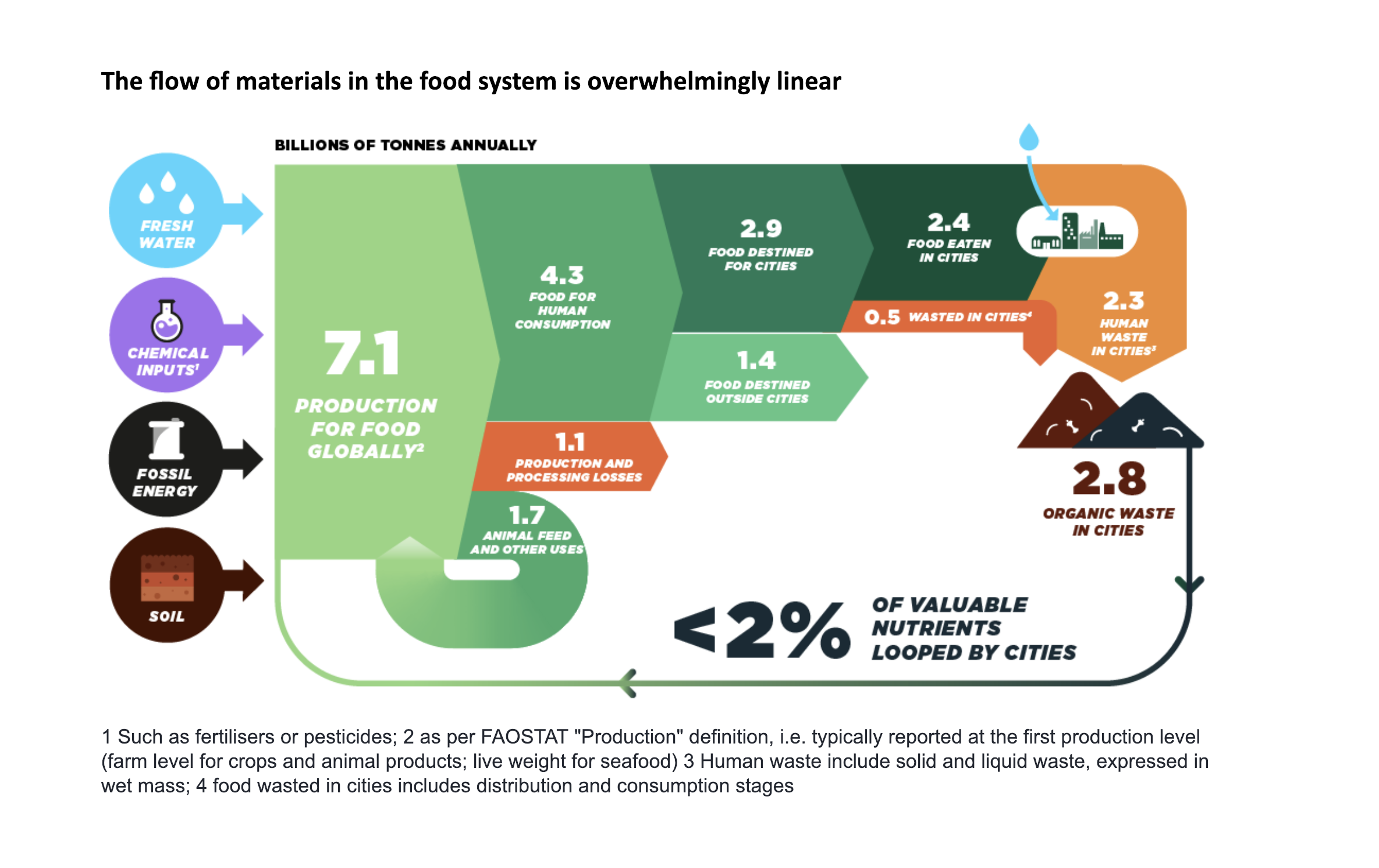

The wasteful way we produce food today relies on extracting finite resources – including phosphorus, potassium, and oil – to grow food in ways that harm the natural systems upon which agriculture depends. The damage includes the degradation of 12 million hectares of arable land a year, a quarter of annual greenhouse gas emissions, and (between 2000 and 2010) almost three-quarters of deforestation. Then, in cities we capture and use an extremely small fraction of the valuable nutrients in discarded food, food by-products and sewage. Air pollution, antibiotic resistance, water contamination and pesticide exposure from food production and mis-managed by-products could claim almost five million lives a year by 2050 – twice as many as the current toll from obesity.

Given that 80% of all food is expected to be consumed in cities by 2050, they have to be central to this story. Today they often act as black holes, sucking in resources but wasting many of them – the final stop in the take-make-waste approach. Equally, cities can influence what food is produced and how, providing them with a unique opportunity to change the game. They can set in motion the transition to a circular economy for food, where food waste is designed out, food by-products are used at their highest value, and food production regenerates rather than degrades natural systems.

Cities and the Circular Economy for Food, a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, identifies three interrelated ambitions that businesses, governments and cities can work towards to put the food system on a more regenerative path.

Here are three ways to build a better circular economy for our food:

1. Source food grown regeneratively and, where appropriate, locally

By interacting with producers in their peri-urban and rural surroundings, cities can use their demand power to move from passive consumers to active catalysts of a transition to a circular economy for food. Examples of regenerative agricultural practices include shifting from synthetic to organic fertilisers, using crop rotation, and promoting biodiversity through increased crop variation. Agroecology, rotational grazing, agroforestry, conservation agriculture and permaculture all fall under this definition. Food players in cities can collaborate with farmers and reward them for adopting these beneficial approaches. While the ability of urban farming to meet people’s full nutritional needs is rather limited, cities can source a significant share of their food from peri-urban areas (within 20 kilometres of cities) as they encompass 40% of the world’s cropland. Such local sourcing can also diversify cities’ food supply, reduce packaging needs and shorten supply chains.

2. Make the most of food

Cities play a crucial role in designing-out food waste as they are where most food eventually ends up. To this end, we have to make the most of our food by ensuring that its by-products are used at their highest value. Rather than disposing of surplus food, cities can redistribute it to help tackle food insecurity. Food supply and demand can be better matched, storage improved to minimise spoilage, and soon-to-expire products discounted. Inedible by-products can be turned into new food products, returned to the soil in the form of organic fertiliser, or turned into biomaterials, medicines or bioenergy. In short, cities can become hubs for a thriving bioeconomy where food by-products are transformed into a broad array of valuable products.

3. Design and market healthier food products

In a circular economy, food is not only healthy in terms of nutritional value, but also in the way it is produced. For decades, food brands, retailers, restaurants, schools and other providers have shaped a significant part of our daily diets. By leveraging their combined power, we can change food design and marketing to make both the processes of food production healthier as well as the food itself. For instance, plant-based proteins require far fewer natural resources, such as soil and water, than their animal counterparts, making them an alternative to explore urgently (while there are regenerative methods for rearing livestock, they likely cannot meet the growing demand for animal protein). Better food design - using food by-products as ingredients and avoiding certain additives, for instance - can further ensure valuable nutrients circulate safely back to the soil or to the wider bioeconomy.

Together these three ambitions are worth $2.7 trillion by 2050. Health costs resulting from pesticide use would decrease by $550 billion and antimicrobial resistance, air pollution, water contamination and food-borne diseases would also reduce significantly. Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to decrease by 4.3 Gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 equivalents, which corresponds to taking one billion cars permanently off the road. Furthermore, 15 million hectares of arable land can be spared from degradation and 450 trillion litres of fresh water saved. Cities can unlock $700 billion by reducing edible food waste and using organic by-products as biomaterials, fertilisers, or sources of energy.

There is an urgent need to realise this vision at scale. To do so will require a global system-level change effort that spans value chains. There will need to be unprecedented collaboration between food brands, producers, retailers, city governments, waste managers and other urban food actors. Flagship demonstration projects in cities around the world will have to be connected with the scaling power of multinational businesses and platforms.

The vision set out in this report offers a way out of the deadlock facing the global food system, with cities mobilising the transition to a circular economy for food both within and beyond their borders. Now is the time to make it happen.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Circular EconomySee all

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Anu Devi and Sarah Franklin

April 30, 2025

Fabienne Robert

April 28, 2025

Poonam Watine and Tim van den Bergh

April 22, 2025

Ellen de Ruiter

April 10, 2025

Charlie Tan and Vuk Trifkovic

April 10, 2025