An economist explains why women are paid less

In rich countries, women enjoy the same education as men - but still fall short on salaries

Laura D'Andrea Tyson

Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School, Haas School of Business, University of California, BerkeleyIt’s a basic principle of fairness: men and women should have the same economic opportunities in life. But all around the world, despite progress and protests and legislation, there is a persistent gap between what men and women are paid.

For every dollar a man earns, on average a woman is paid 54 cents. Based on today’s rate of progress, it will take 202 years for this gap to close, according to the World Economic Forum. As this chart of major OECD economies shows, the discrepancy plays out all around the world.

But what’s going on behind those numbers? Both outright discrimination and a complex web of factors that influence and constrain the options open to women, according to the American economist Laura Tyson. She pinpoints parenthood as the moment the gap widens, with mothers taking a wage penalty while fathers enjoy a premium.

The below is an edited transcript of a conversation with Laura Tyson, Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School at Berkeley.

"There are many factors behind the wage disparity between men and women. I would start simply with the fact that until recently there were different levels of educational attainment for men and women, and educational attainment is a major determinant of earnings. But during the past 20 years, the world has made tremendous progress on eliminating the educational differences between men and women, so these differences now play a much smaller role in gender earnings differences particularly among younger workers with comparable educational attainment levels.

So, let's go now to some other factors that affect the gender gap in earnings.

Women choose different occupations from men. And there are large and persistent differences in the earnings of different occupations. Around the world, occupations like teachers pay less than occupations like engineers. So gender differences in occupational choice affect gender differences in earnings. Why do women and men make different occupational choices. Are there not enough role models for women in higher paying occupations? Are there barriers to female advancement in those occupations? The answer to both questions is yes. Moreover, even within high-paying occupations, women tend to be employed at lower levels of the occupational hierarchy: there is a persistent gender gap at higher ranks of management and leadership within occupations and this in turn contributes to the gender pay gap within them.

There are related gender differences in earnings by industry or sector of economic activity. Around the world, men are more likely to hold jobs at any skill level in manufacturing, a sector that pays relatively high earnings, while women are more likely to hold jobs in educational services, a sector that pays considerably less than manufacturing.

Gender differences in employment by occupation and industry are important determinants of gender differences in earnings around the world. So to understand and reduce the gender gap in earnings it is necessary to understand and reduce the gender differences in employment by occupation and sector.

What's the World Economic Forum doing about the gender gap?

Women around the world are also more likely than men to work part-time. And part-time work, even for the same kind of job in the same occupation and sector, has a lower hourly wage with fewer social protections and benefits than comparable full-time work. According to the ILO, women account for about 57% of global part-time work, and the earnings gap between comparable full-time and part-time work is in the order of 10%.

There is also evidence that motherhood and associated gender differences in household care responsibilities are significant factors behind the gender pay gap.

There's evidence of a wage penalty for motherhood: all else being equal, there is a negative relationship between a woman’s wage and the number of children she has. According to OECD data, the motherhood penalty amounts to about a 7% wage reduction per child. There is also some evidence of a fatherhood premium: a positive relationship between a man’s wage and the number of children he has.

When you compare men and women with comparable educations at the beginning of their careers, working full-time in the same occupation and sector, the gender gap in earnings has largely disappeared in many advanced industrial economies. Same education, same work, same wage.

Five to ten years later, often after the arrival of children, the gender gap in earnings appears. A non-existent wage gap becomes a significant and growing wage gap.

Women often choose to move to part-time employment or to step out out of a career promotion pathway in order to have more time for motherhood and childcare when their children are young. If they return to work full-time, they are often forced to accept a lower wage compared to the wage they would have earned had they stayed in their original job.

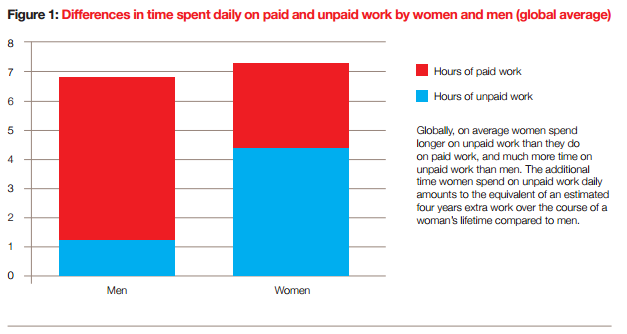

There is a significant amount of work associated with running a household and raising children. That work exists. And right now, not just in advanced industrial countries but around the world, that work is disproportionately done by women. And it's not paid.

An important step to closing the gender pay gap is the more equitable sharing of parental responsibilities between men and women. Paid parental leave policies that provide both maternity and paternity leave help achieve this goal, increasing the participation of fathers in child care and reducing gender stereotyping in childcare and related household responsibilities. When paternity care is non-transferable, men are more likely to take advantage of it, reducing the gender differences in labour force participation rates associated with children. Paternity leave is frequently cited as a very important policy to reduce or eliminate the pay differential resulting from the motherhood penalty and the fatherhood premium.

Discrimination, stereotyping and implicit biases still play a role. Finally, and this is significant: even taking out the education effect, the occupation effect, the sector effect, the part-time work effect,and the motherhood and fatherhood effects, a gender gap in earnings remains. This gap is evidence of persistent discrimination, stereotyping and implicit biases in earnings and promotion opportunities for women. Government policies, legal protections, and changes in business practices, such as regular pay assessments of earnings by gender and pay transparency, are necessary to combat these sources of the gender gap in pay.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Gender Inequality

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Marielle Anzelone and Georgia Silvera Seamans

October 31, 2025