Mosquito-borne diseases could spread to a billion more people as climate warms

A study has found that nearly one billion people could face “their first exposure” to a host of mosquito-borne diseases by 2080.

Image: REUTERS/Juan Carlos Ulate

Stay up to date:

Global Health

Nearly one billion people could face “their first exposure” to a host of mosquito-borne diseases by 2080 under extreme global warming, a study finds.

Countries in Europe, including the UK, would be the most affected by the influence of extreme warming on diseases such as dengue fever, Zika and chikungunya, the research says.

Meeting the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting warming to below 2C could greatly stem the increase, the authors say. However, this would also shift the burden of disease from wealthy mid-latitude countries to the developing tropics.

The findings “point to a future world where a much larger proportion of the human population will be at risk of viruses borne by mosquitoes,” a scientist tells Carbon Brief.

Blood suckers

There are around 3,500 species of mosquito on Earth. The new study, published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Disease, focuses on two species that are particularly dangerous to humans: the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus).

Both mosquitoes carry viral diseases such as dengue fever, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya – which they pass on to humans when feeding on their blood.

The insects are currently found throughout the tropics, including in central Africa, Asia and Latin America and, to a lesser extent, in the US and southern Europe.

The research aims to estimate how the mosquitoes’ geographic range is likely to change with varying levels of future climate change. It also estimates how the seasonality of disease risk and the overall number of people exposed could change.

To do this, the authors used modelling to simulate how the risk of disease transmission could change under four scenarios of future climate change, known as the “Representative Concentration Pathways” (RCPs). These pathways range from a scenario where the world meets the Paris target of limiting warming to “well below” 2C (“RCP2.6”), to a scenario with no climate action where future global warming could reach 5C (“RCP8.5”).

The model not only considers how warming could impact disease transmission, but also a range of mosquito traits. For example, the model considers how warming could affect the rate at which mosquitoes reproduce. (Female mosquitoes only seek human blood when they have developing eggs.)

The simulations assumed that the future world population remains at around 2015 levels, Ryan says:

“We wanted to keep a consistent denominator in our calculations. This provides almost a ‘conservative’ estimate – because it’s not including inflated numbers due to growth.”

First time risk

The results show that, under the most extreme scenario of future climate change, almost one billion people could be exposed to mosquito-borne diseases for the first time by 2080.

The chart below shows the top 10 regions where people could face a new risk from viral diseases borne by the yellow fever mosquito (left) and the Asian tiger mosquito (right).

The number of people exposed to mosquito-borne diseases for the first time by 2080 is likely to be highest in Europe, says lead author Prof Sadie Ryan, a researcher of medical geography from the University of Florida. She tells Carbon Brief:

“We will see the largest numbers of new exposures to Aedes borne disease risk in Europe, followed by East Africa. Although we do, sadly, associate tropical febrile [feverish] diseases with East Africa already – focusing largely on malaria – we really don’t associate most of Europe with them.”

Parts of the UK could face disease risk for the first time if climate change is extremely high, she says:

“Southern England will attain sufficient numbers of months of suitable temperatures under the worst-case scenario for both mosquito species. This suggests that a population of these mosquitoes could persist locally for a few months of the year, capable of transmitting viruses, setting the stage for possible introductions and outbreaks. This scenario is similar to current-day Italy, which has seen outbreaks of Chikungunya, vectored by A. albopictus mosquitoes.”

The maps below show the current geographic range of both mosquito species (top) and how these ranges are likely to change by 2050 (middle) and 2080 (bottom) under extreme warming. On the maps, colour is used to indicate the number of months in a year with disease transmission risk.

The maps show how a new risk could emerge in southern England, parts of Scandinavia and Canada as the world warms. However, the risk of disease transmission from the Asian tiger mosquito appears to shrink in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

This is because these regions could become too hot for the Asian tiger mosquito, which can tolerate temperatures up to 29.4C, the authors say. (The yellow fever mosquito can tolerate temperatures up to 34C, they add.)

Target turmoil

Though the results suggest the worst-case climate scenario would lead to the largest increase in people exposed to mosquito-borne diseases, the findings for the other scenarios are less straightforward.

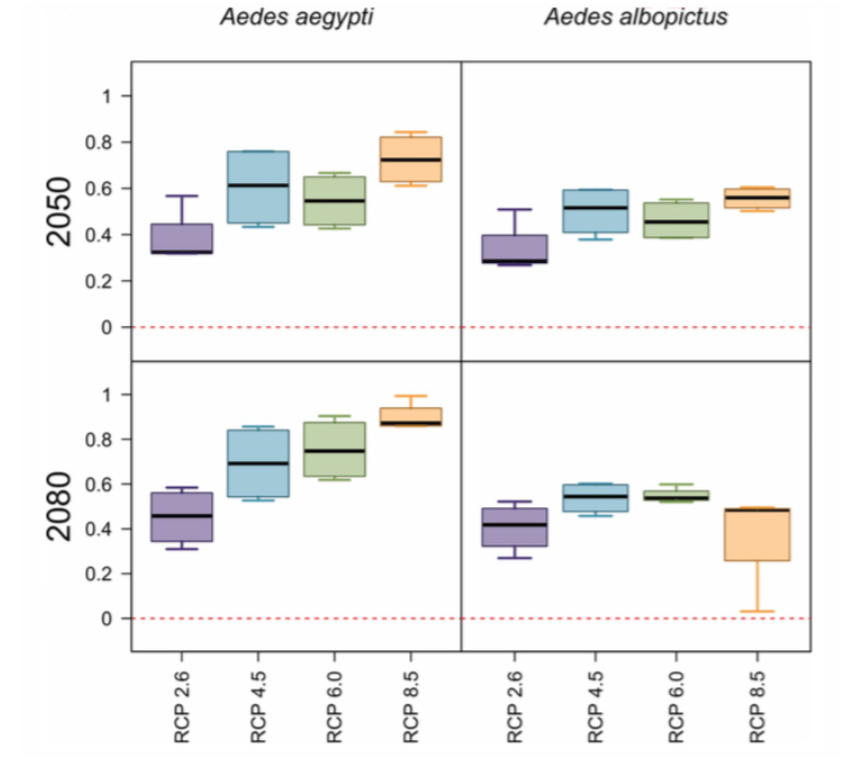

The charts below show the projected net changes to the number of people exposed to disease risk from the yellow fever mosquito (left) and the Asian tiger mosquito (right) under the four future climate change scenarios. Results are shown for 2050 (top) and 2080 (bottom).

The results show that limiting warming to below 2C (RCP2.6) could nearly halve the number of people exposed to disease risk from the yellow fever mosquito by 2080.

However, the number of people exposed to disease risk from the Asian tiger mosquito appears to be largest in “middle-of-the-road” scenarios (RCP4.5 and RCP6.0).

This reflects the fact, under moderate warming, the Asian tiger mosquito could expand polewards, but also remain a driver of disease in the tropics. The authors say:

“Because the upper thermal limit of A. albopictus transmission is relatively low (29.4C), the largest declines in transmission potential in western Africa and southeast Asia are expected with the largest extent of warming, while less severe warming could producer broader increases and more moderate declines in transmission potential.”

Infectious

The findings show that “climate change is a looming threat to global health and that mitigation is essential”, Ryan says:

“The sheer number of people newly at risk of potential viral transmission by these two mosquito species and their pathogens is heading for nearly a half a billion in the next few decades. However, this viral risk is but one of many climate change induced vulnerabilities we face as the whole of humanity.”

The research is “important”, but does not consider all of the factors important to mosquito survival, including the availability of potential breeding sites, says Prof Andy Morse, a climate impacts researcher from the University of Liverpool. (Earlier this month, Morse and colleagues published a paper finding that climate change could bring yellow fever mosquitoes to southern England.) He tells Carbon Brief:

“Because the model is only, it seems, thermally driven, it has transmission over many months of the year in desert areas where there is a lack of breeding sites and rainfall and on the whole few, if any, humans to infect. Exclusion of regions in the world where habitat or artificial breeding sites are not available is something that should have been addressed in the analysis.”

Despite its limitations, the research paper clearly shows that climate change will lead to the increased spread of mosquito-borne diseases, he adds:

“Even with its simplifications and possible omissions, I think this is an important paper that points to a future world where a much larger proportion of the human population will be at risk of viruses borne by mosquitoes. We can act now to protect our homes and communities from this threat through more careful management of potential breeding sites.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Madeleine North

August 13, 2025

Charlotte Edmond

August 11, 2025

Adriana Banozic-Tang and Heng Wang

August 5, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

July 30, 2025

Pranidhi Sawhney and Adam Skali

July 29, 2025