The Japanese have a word to help them be less wasteful – 'mottainai'

How linking words with emotions ensures sustainability.

Image: REUTERS

Stay up to date:

Japan

The Japanese have a word for the sense of regret they feel when something valuable is wasted: 'mottainai' (もったいない). It can be translated as “don’t waste anything worthy” or “what a waste”, and has come to represent the island nation’s environmental awareness.

Rooted in the Buddhist philosophy of frugality and being mindful of our actions, mottainai came to prominence in the post-war days of scarcity and is now handed down from grandparents to grandchildren.

But it’s also connected to Japan’s indigenous religion, Shintoism, in which nature and even man-made objects are imbued with their own ‘kami’ or spirit – meaning things have innate value and are not to be disrespectfully discarded.

Mottainai can be seen in the way Japanese decluttering champion Marie Kondo gives thanks to individual items of clothing before laying them in a pile for charity. It also explains why the country is a world leader when it comes to the 3Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle.

The term was also used by Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, who founded the Greenbelt Movement, to encourage Africans to eliminate plastic waste.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Getting on top of garbage

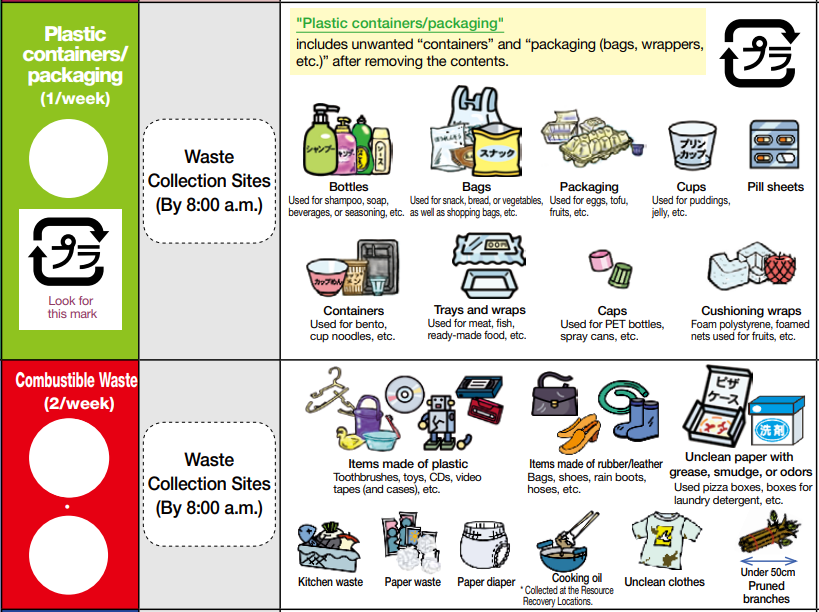

Japan’s sophisticated waste management system has lessons for the rest of the world: everything from polystyrene to packaging for pills can be separated and recycled.

The Basic Act for Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society (Basic Recycling Act) came into force in 2000 – to promote the 3Rs and proper waste management – with every October designated as 3R Promotion Month.

Supermarkets now have PET bottle shredders - providing shopping tokens in exchange for plastic - that cut down on the emissions created by collections. PET resin is then used to make everything from clothes and carpets, to new bottles.

And there are apps that feature “dictionaries” to help people sort their waste, as well as alarms to remind people what to put out for collection on a given day.

There are good reasons behind Japan's motivation to tackle its waste.

In the bubble economy of the 1980s and early 1990s, production of plastics grew quickly, and so, too, did the country’s waste problem. Between 1993 and 2000, the number of plastic bottles produced tripled to more than 360,000 tonnes, according to Japan's environment ministry.

Today, Japan is second only to the US as the world’s biggest generator of plastic packaging waste per capita, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. But in a report, last year, UNEP noted,“thanks to a very effective waste management system and a high degree of social consciousness, [Japan] accounts for relatively limited leakages of single-use plastics in the environment”.

Of the 9.4 million tonnes of plastic waste produced by Japan each year, the government says only 25% is recycled, while 57% is incinerated for “energy recovery” and 18% goes into landfill or is burned.

A burning issue

Japan’s landmass is limited, so there’s little space for landfill sites, meaning garbage that can’t be recycled is often burned.

While collections vary between prefectures, in Nakano City items including food waste, unclean pizza boxes, diapers and waterproof rubber boots are collected for incineration, which generates electricity.

However, burning waste produces harmful gases, including dioxins, which were reported to be contaminating soil and even breast milk. So over the past two decades, the country has been working on improving technology to reduce emissions from incineration in order to protect people and the environment.

Between 1997 and 2003, dioxin emissions fell by 98%, according to the government.

What is Loop?

Towards zero-waste

In the run-up to the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, when all eyes will be on Japan, its drive to boost its green credentials continues apace.

There are now 26 “environmentally harmonious” certified eco-towns, according to the environment ministry. And one village has taken mottainai to another level by aiming to become 100% zero-waste by 2020.

In Kamikatsu, Akira Sakano set up the Zero Waste Academy. Although 80% of the village’s waste is kept out of incinerators and landfill, Sakano told the World Economic Forum that manufacturers need to do more to help them reach 100%.

“Products need to be designed for the circular economy, where everything is reused or recycled. These actions really need to be taken to businesses and incorporate producers, who need to consider how to deal with the product once its useful life has ended.

“It’s important, no matter the obstacles, to keep striving to achieve the 100% goal. It’s important that world leaders now take their turn to make circular economy happen,” Sakano said.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Circular EconomySee all

Anne Raudaskoski

June 19, 2025

Jon Creyts and Anis Nassar

June 16, 2025

Jan Rosenow, Simon Sharpe and Max Collett

June 11, 2025

Paul Holthus and Jack Hurd

June 4, 2025

Ryan McClanaghan and Lisa Chamberlain

May 23, 2025

Vivin Rajasekharan Nair and Gokul Krishna A

May 23, 2025