5 things COVID-19 has taught us about inequality

The pandemic has shone a light on existing inequalities.

Image: REUTERS/Yuriko Nakao

Explore and monitor how COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Stay up to date:

COVID-19

- Coronavirus has brought to wider consciousness inequalities in areas from healthcare to technology.

- These inequalities are felt along various lines, from ethnicity to income.

- Minority groups and people with disabilities face multiple barriers in access to essential services.

The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown socio-economic inequalities into sharp relief.

From access to healthcare and green spaces, to work and education, here are five areas of society where coronavirus has shown up real disparities.

1. Access to green spaces

Studies have shown the benefit of green spaces for our mental and physical health. And, with millions in various forms of lockdown, unequal access to these spaces has become a hot topic.

Recent research in South Africa has shown that 'white' neighbourhoods are 700m closer to public parks and have 12% more tree cover than areas with predominantly black residents.

Meanwhile, a 2017 study in Germany highlighted inequalities in access to urban green spaces in relation to income, age, education and numbers of children in households.

And a 2010 study showed that the most deprived census wards in the UK had, on average, just a fifth of the area of green space available to the most affluent wards.

You can read more about green spaces, their health benefits and the inequity that persists here.

2. Health access and outcomes

The pandemic has highlighted inequalities in access to healthcare and health outcomes for different groups.

Research in Europe has shown that, even in comparatively well-developed healthcare systems, inequality in access to health services persists. A 2018 report by the European Commission (PDF) says: "the lowest income quintiles are among the most disadvantaged groups in terms of effective access to healthcare".

The report highlights issues along the lines of gender, race and residence status, with women and migrants both facing particular difficulties.

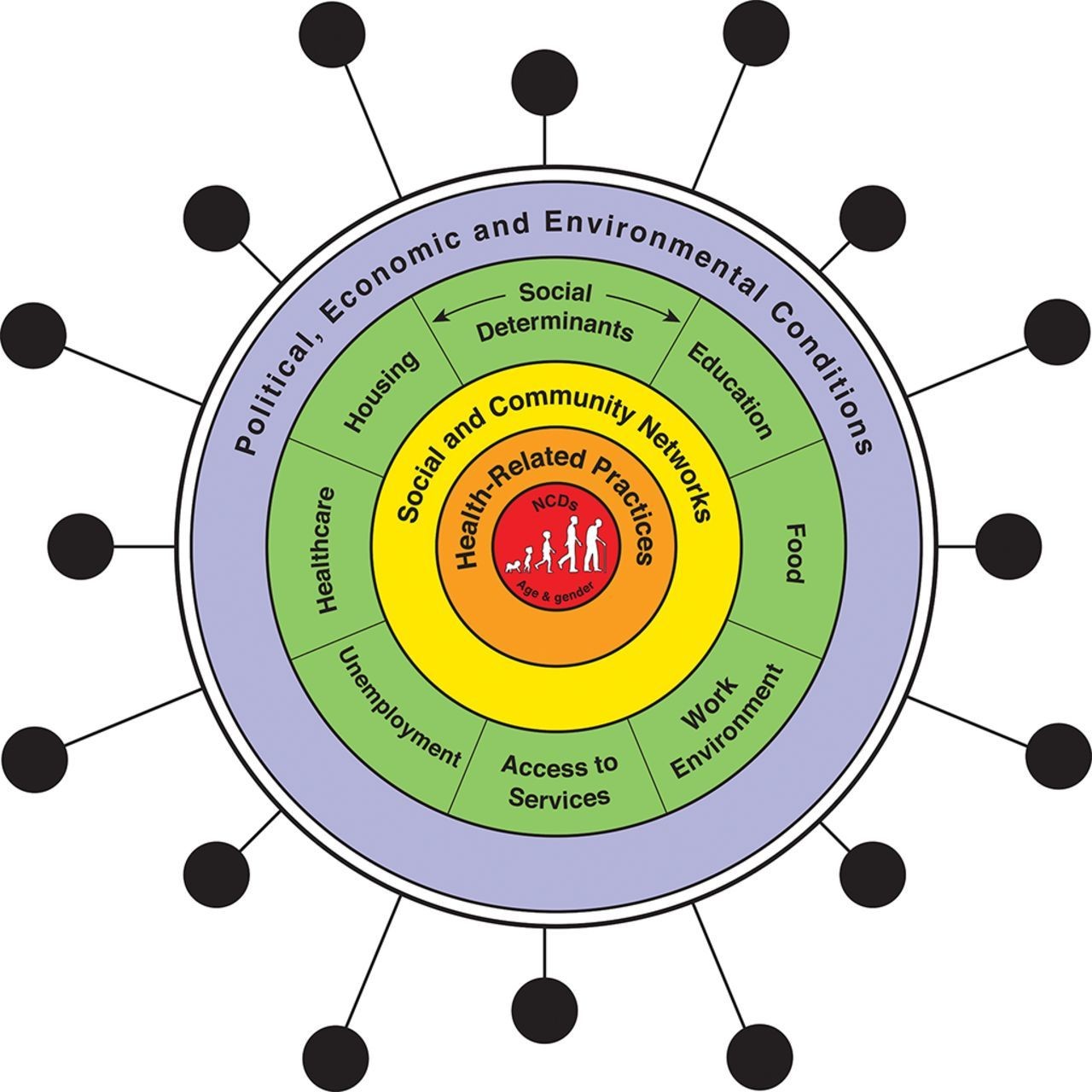

Significantly, the pandemic has highlighted the impact of socio-economic conditions on health. As the World Health Organization explains, "there is ample evidence that social factors including education, employment status, income level, gender and ethnicity have a marked influence on how healthy a person is".

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

And initial research in the UK, for example, has shown that minority ethnic groups have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. A similar pattern has emerged in the United States, too.

These disparities within countries are all on top of the inequalities that exist between countries. For example, 95% of tuberculosis deaths occur in the developing world, and global life expectancy can vary by as much as 34 years.

Eighty-seven percent of premature deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) occur in low- and middle-income countries. And, in many of these countries, the cost of these diseases push people into poverty, hurting development and exacerbating health issues.

For more on the COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities, read this essay in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health.

What is the World Economic Forum doing to manage emerging risks from COVID-19?

3. The digital divide

Millions of workers and school children have been sent home, forced to work remotely by lockdowns and social distancing rules.

But, this has highlighted gaps in access to technology and the internet.

For example, some 50% of people (that's more than 600 million individuals) in India don't have access to the internet.

And in many African countries the percentage is much higher. For these millions of people, remote working or education is little more than a fantasy. In India classes have been delivered by loud speaker in some rural areas.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

And, there's also a significant disparity within countries. Take the US for example, where differences persist along income, age, race and urban/rural lines. For example, according to Pew Research Center, 15% of adults in rural areas say they do not use the internet, compared to 9% in urban areas. Meanwhile, 8% of white people say the same, compared to 15% of Black people.

And, COVID-19 has exacerbated this. Parents with lower incomes were much more likely than those with higher incomes to say their children will face 'digital obstacles' during the pandemic.

You can read more on a Microsoft initiative to tackle this divide here.

4. Jobs in a virtual world

There's a digital divide in play for adults too - both between countries and within them. Data suggests that the share of people who work from home is closely linked to internet penetration.

(Note: agriculture workers omitted in the below chart)

And, those with poor internet connections at home, even in countries with high levels of internet access, will find it hard to cope in a new virtual, video-conferencing world.

But, there are other inequalities at play as well.

Higher-educated and -skilled workers are more likely to work in occupations where remote working is a possibility, according to research in the Netherlands.

As a result, lower-skilled workers are more prone to job losses or reduction in hours.

A study in Germany showed a similar pattern, with those with higher incomes having more opportunities to do remote work.

Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom believes this trend is "generating a time bomb for inequality".

In a Q&A with the university, he explained the impact of his research into the societal impact of working from home:

Our results show that more educated, higher-earning employees are far more likely to work from home – so they are continuing to get paid, develop their skills and advance their careers. At the same time, those unable to work from home – either because of the nature of their jobs, or because they lack suitable space or internet connections – are being left behind. They face bleak prospects if their skills and work experience erode during an extended shutdown and beyond.

”You can read that Q&A in full here.

5. Accessibility and disability

Many people with disabilities have been disproportionately affected during the pandemic.

Research in the UK has shown that two-thirds of people with visual impairments feel they've become less independent since the start of lockdown.

And, also in the UK, more than two-thirds of COVID-19 deaths have been people with a disability.

The WHO has also warned of the risks those with disabilities face during the pandemic, including an increased risk of developing severe disease. Social distancing can also be hard for these groups because of the need for additional care and support.

Disruptions to essential services might also put people at risk.

But, this is nothing new. The WHO explains that "people with disability experience poorer health outcomes, have less access to education and work opportunities, and are more likely to live in poverty than those without a disability".

For example, across the EU, less than one person out of two with basic activity difficulties is employed, according to Eurostat.

And, significantly in the context of the pandemic, people with disabilities can face barriers in access to essential services - including healthcare. The WHO reports on a survey of people with serious mental disorders. Between 35-50% in developed countries and 76-85% in developing countries had received no treatment in the previous year.

The COVID-19 pandemic and response have brought pre-existing systemic inequalities like these - and the need to tackle them - into sharp focus.

In response, the World Economic Forum's UpLink platform has launched the COVID Social Justice Challenge, a competition to find ideas and solutions which tackle social inequalities and injustices within the COVID response and recovery.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Gaurav Ghewade

April 23, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi and Mizuho Ota

April 7, 2025

Charlotte Ersboll and Kusum Kali Pal

April 7, 2025