This member of the banana tree family could help us cut COVID-19 plastic waste

Stay up to date:

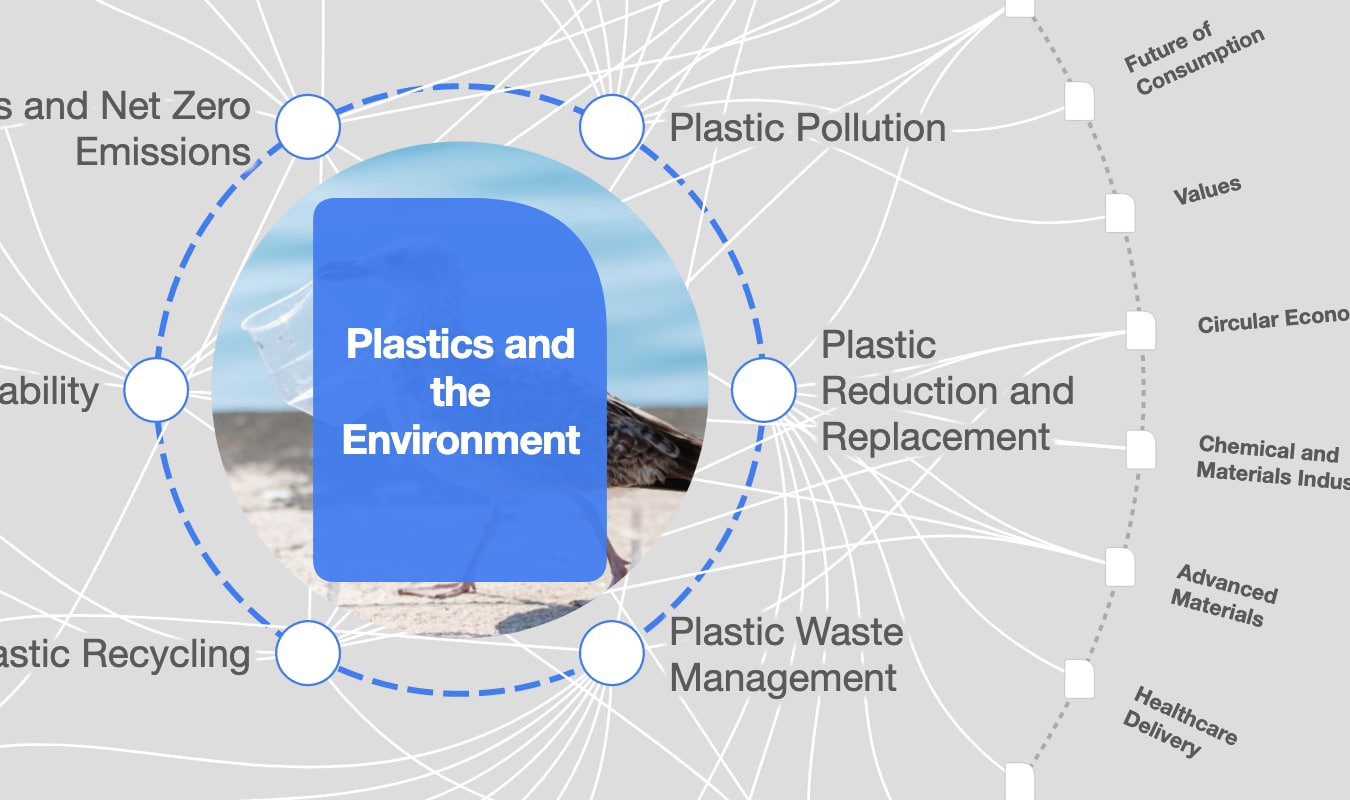

Plastic Pollution

- The abaca tree, a relative of the banana, produces fibre that’s being made into COVID-19 PPE products, including facemasks.

- Conservationists say single-use plastic PPE is adding to marine pollution.

- Abaca fibres - used in banknotes, teabags and Mercedes Benz cars - are as tough as polyester but break down organically.

- Philippines is leading producer of abaca fibre, delivering 85% of global supply.

In the Philippines, long golden fibres from the abaca tree hang drying in the sun. They could be part of your next face mask.

According to Bloomberg, the Philippine government expects demand for biodegradable abaca to grow exponentially in 2020, with 10% of all production being diverted to medical uses. Factories are doubling output.

It comes as the consequences of single-use plastic PPE are becoming clear. There are reports of plastic face masks washing up on beaches, adding to the estimated 8 million metric tons of plastic that enter the ocean each year.

From greeting cards to life-saving fibres

Abaca fibres come from the trunks of the abaca tree that are commercially grown in just a few countries. The Philippines is the world’s leading producer, accounting for around 85% of global supply in 2017, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

In recent years, abaca products have been finding favour as a durable substitute for synthetics. But they have a much longer history.

What is the World Economic Forum doing about plastic pollution?

In the 19th century they were used to make rigging on ships as well as sturdy manila envelopes. More recently, Mercedes Benz has used them to replace glass fibre in car parts and they form up to 30% of Japan’s yen banknotes. But abaca’s biggest modern use is in specialty papers, such as tea bags and high-end greeting cards. That was until 2020.

This year, abaca paper was discovered to have life-saving properties. The Philippine government tested it following the COVID-19 outbreak and it found performed well against standard plastic masks on water resistance and conformed to international standards. There’s now a rush for abaca.

“People see this pandemic lasting for some time, so even small companies are trying to make protective equipment, which require our fibre,” abaca exporter Firat Kabasakalli from Dragon Vision Trading told Bloomberg. “We are getting a lot of inquiries from new clients abroad.”

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Plastic pollution

The UN’s trade agency, UNCTAD, has warned of “a tidal wave of COVID-19 waste” hitting streets, beaches and oceans.

“Plastic pollution was already one of the greatest threats to our planet before the coronavirus outbreak,” says Pamela Coke-Hamilton, director of international trade at UNCTAD. “The sudden boom in the daily use of certain products to keep people safe and stop the disease is making things much worse.”

The UN says 75% of coronavirus-related plastic is likely to become waste, much of it marine pollution. It highlights a report by Grand View Research, which shows the market for face masks is expected to increase by more than half every year until 2027.

Yet despite its promise, abaca can only be part of the solution. While output is now increasing, the crop’s global production is constrained by factors including the limited number of countries where it is grown, few subsidies and intense competition from cheaper mass-produced plastics.

UpLink, the World Economic Forum’s early-stage innovation initiative, is enabling and accelerating the purpose-driven entrepreneurs that are essential for a net-zero, nature-positive, and equitable future. To find out more and join the UpLink community, click here.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Global RisksSee all

Allison Shapira

November 14, 2025

Isabel Cane and Rob Strayer

November 13, 2025

Hamed Ghiaie and Filippo Gorelli

October 29, 2025

Brad Irick

October 23, 2025

Michelle You

October 23, 2025

Sam Butler-Sloss and Daan Walter

October 22, 2025