Why the global trade of chemicals is key to COVID-19 recovery

Chemicals are vital to the smooth-running of our societies. Image: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Tobias Radel

Industry Lead Chemicals and Natural Resources; Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Russia, Accenture Strategy & Consulting- Chemical and materials are at the heart of responses to global shocks like the current pandemic.

- Their global availability must be secured for effective response, fast recovery and lasting resilience building.

- A functional trade system, increased cooperation across sectors, and greater business flexibility are essential to resilience.

As the world continues to navigate the complexities of an ongoing pandemic, at any given time millions of tons of the building blocks behind personal care, digital communications, safe packaging or pharmaceuticals – in short, chemicals – are being transported globally to support the world’s response, recovery and long-term resilience.

It is fair to say that a global health, economic or social recovery won’t be possible without the essential ingredients behind protective masks, mattresses or wind turbine blades being available globally.

But this cannot be achieved without functioning global value chains. Without an efficient flow of goods and services, investment capital and knowledge, socio-economic systems will not be rebuilt. So what is being done to ensure they can be?

The World Economic Forum’s Chemical and Advanced Materials Industry Action Group (IAG), supported by the Forum and in collaboration with Accenture, has identified opportunities to increase sectorial and societal resilience through collaborative action. As part of this work, we highlight some of the underlying trends defining global value chains and their importance in building more resilient socioeconomic systems.

Global chemical trade in retreat

The pursuit of efficiency has defined the chemical industry landscape in the last two decades. Between 1998 and 2008, enabled by trade agreements, harmonization of standards and regulatory adjustments, chemical companies located plants in the lowest cost locations or near the largest demand centres, while investing globally in world scale increments. Global chemical exports in the same period increased from around $400 billion to around $2.1 trillion, resulting in a solid increase in chemical trade as a share of chemical GDP.

Since the 2008/09 financial crisis, however, chemical trade has declined steadily (see graphic below). The reasons are many, including a loss of momentum in some growth markets, the impact of trade interventions, the reduced influence of global institutions, and more scrutiny over foreign direct investments. The same decade also saw import regions become self-sufficient, with geographic shifts in customer industries as a result of labour cost increases in east Asia and further automation.

Beyond the cross-border movement of goods, other dimensions of a much broader globalization process have developed:

• A surge in bilateral agreements has in many cases replaced global multilateral schemes

• The mobility of whole plants and technology platforms has enabled companies to make and reverse investment decisions much more flexibly

• Automation and global competition have impacted the services sector in several ways

These factors provide chemical companies with much broader options when it comes to reconfiguring their value chains, but it also creates a more volatile environment in which transparency and resilience against potential shocks become important alongside cost and speed.

COVID-19 further politicizes trade

With COVID-19 exacerbating these economic undercurrents and the introduction of new political complications, three trends appear to be here to stay:

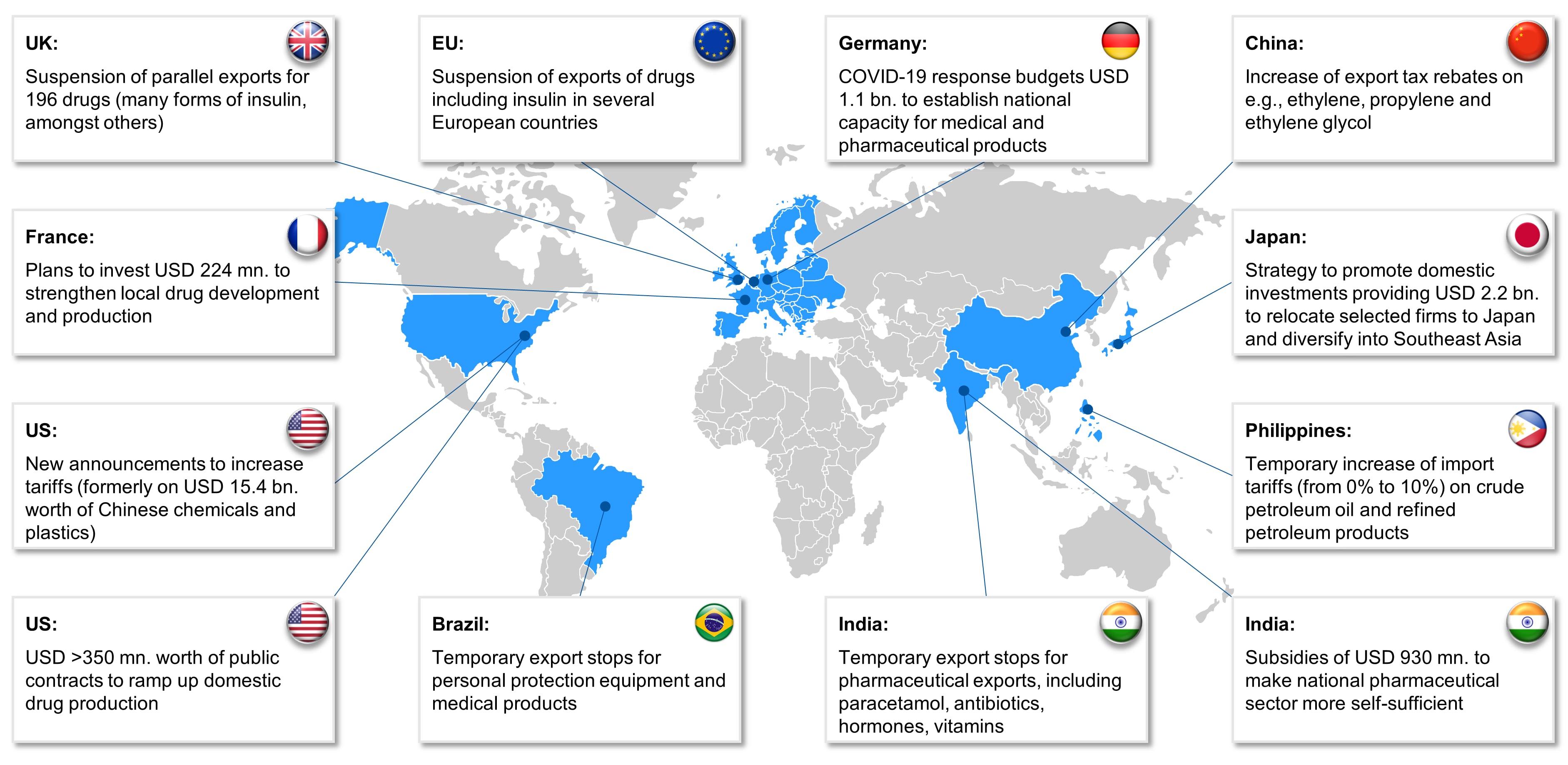

1. Increasing political interventions on the flow of goods. Countries around the globe are attempting to secure critical materials or protect local industries. Export bans on certain medical supplies have become a global phenomenon. For example, in March 2020, India banned 10% of the country’s pharmaceutical exports, including paracetamol, antibiotics, hormones, and vitamins. Stocks in several importing countries ran dangerously low and required governments to intervene or announce retaliatory measures, before the bans were partially lifted. Several European countries also restricted exports, including insulin. When the global demand nearly disappeared, additional trade interventions were deployed to protect national industries. For example, China increased export tax rebates on ethylene, propylene and ethylene glycol, and India debated a 15% “COVID tax” on all chemical and petrochemical imports.

2. Government incentives to re-shore. The inherent risks of longer, more dispersed global value chains have become evident, and are leading to a stronger focus on regionalization (see graphic below).

Japan set aside $2.2 billion to fund the repatriation of the manufacturing capacities of Sumitomo Rubber, Shin-Etsu Chemical and others as well as their diversification into south-east Asia. European governments are also stepping up their involvement in national business interests. France plans to invest $224 million to help fund the national development and production of drugs, including paracetamol. Germany’s COVID-19 response includes a $1.1 billion budget to establish national capacity for medical and pharmaceutical products. The US has awarded public contracts to ramp up domestic drug production, including a $354 million contract for generic drugs awarded to Phlow, a Virginia-based startup.

Eastman Kodak will also receive a $765 million loan from the US International Development Finance Corporation to launch Kodak Pharmaceuticals, a new division in the company that will produce critical, generic active pharmaceutical ingredients (API). This is in line with corporate efforts aiming to reduce exposure to global trade flows disruptions through localizing manufacture.

3. Frequency of shocks creates need for resilience. As shocks and disruptions are becoming more prevalent, the motivation to intervene and incentivize the localization of production in the name of resilience may continue to increase. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report 2020 highlighted the increased frequency of climate-related shocks, and sociopolitical volatility in geographies across the world. They translate directly into economic and financial instability, and threaten the efficiency of the global trade of chemicals.

A more detailed view of supply chain vulnerability

Behind many recent government interventions into the chemical market lies the assumption that global production of critical goods has become too concentrated, that COVID-19 has disrupted too many supply chains, and that countries are at risk of being cut off from the supply of essential products. Chemical companies therefore face pressure to re-evaluate their value chains. However, a reconfiguration towards a more regional approach, from an economic and risk perspective, is in fact justified only in specific cases, when the following factors come into play:

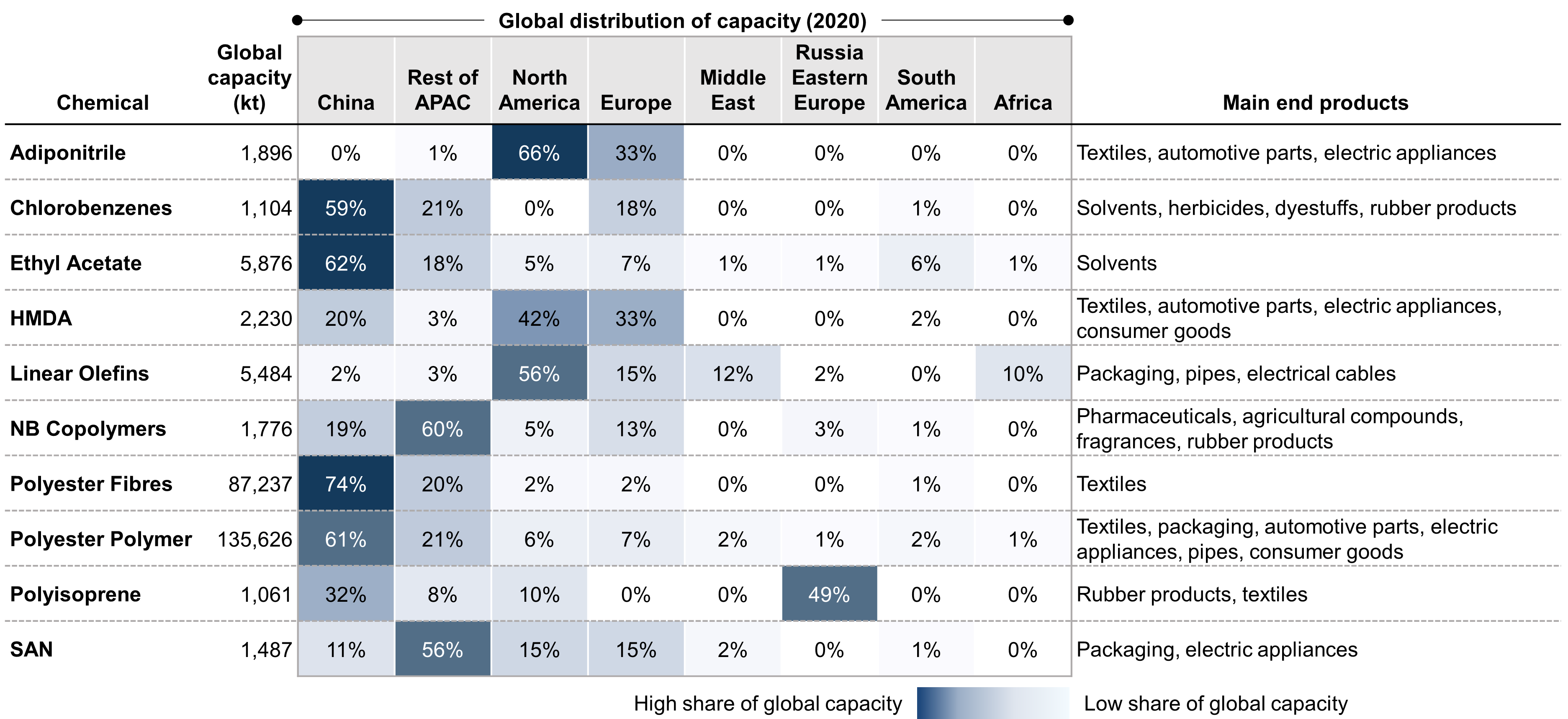

The concentration of supply is high for many chemical product categories

Production has become highly concentrated in a few value chains over the years. This occurs where the critical mass of assets is high, intellectual property is concentrated with a few players, demand is clustered in maturing end industries, or where certain hubs offer – often government-sponsored – advantageous production conditions. Early steps in materials value chains are particularly prone to concentration, as manufacturing of ingredients and materials often requires scale economies and access to feedstock. As a result, many base chemicals or intermediates have become more concentrated in specific regions.

A detailed view at product or precursor level shows geographic and supplier concentration

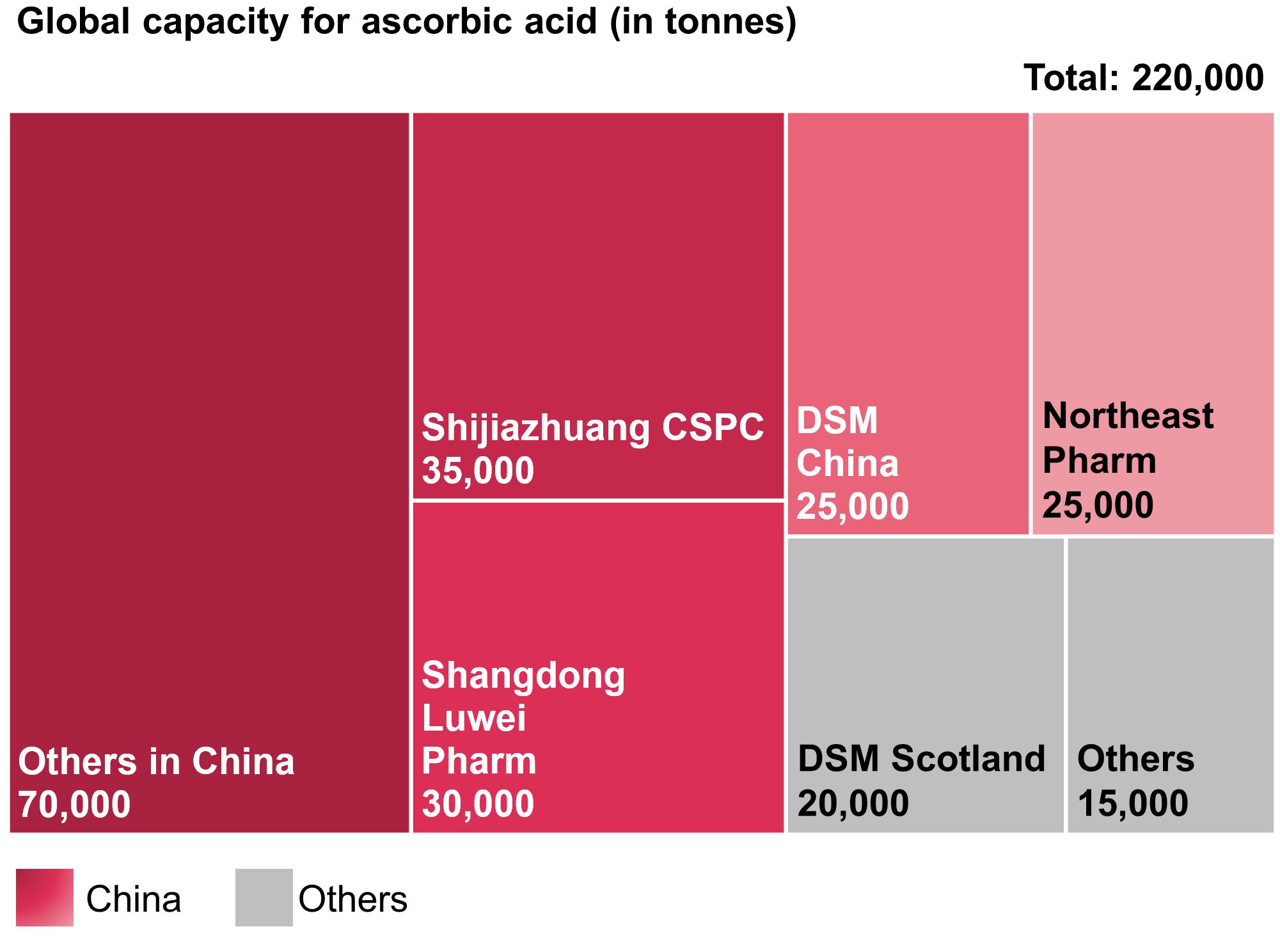

An analysis must take single product lines and their applications in critical end products into focus. For example, more than 80% of today’s global capacity for ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is concentrated in China, as local manufacturers use efficient fermentation processes and international producers are attracted to the low-cost and low-regulation environment. Significant global overcapacity and price pressures have left only one major plant in Scotland, and no significant capacity in the Americas. Besides general supply concerns, this situation makes manufacturers of products using vitamin C dependent on pricing decisions and regulatory changes (e.g. environmental standards) in a specific country. A detailed look at the China supply base reveals that in addition to the top four producers of vitamin C (accounting for 50% of world production), the remaining 30% of global production share is fragmented among smaller suppliers, leaving options for sourcing diversification.

Special focus on precursors

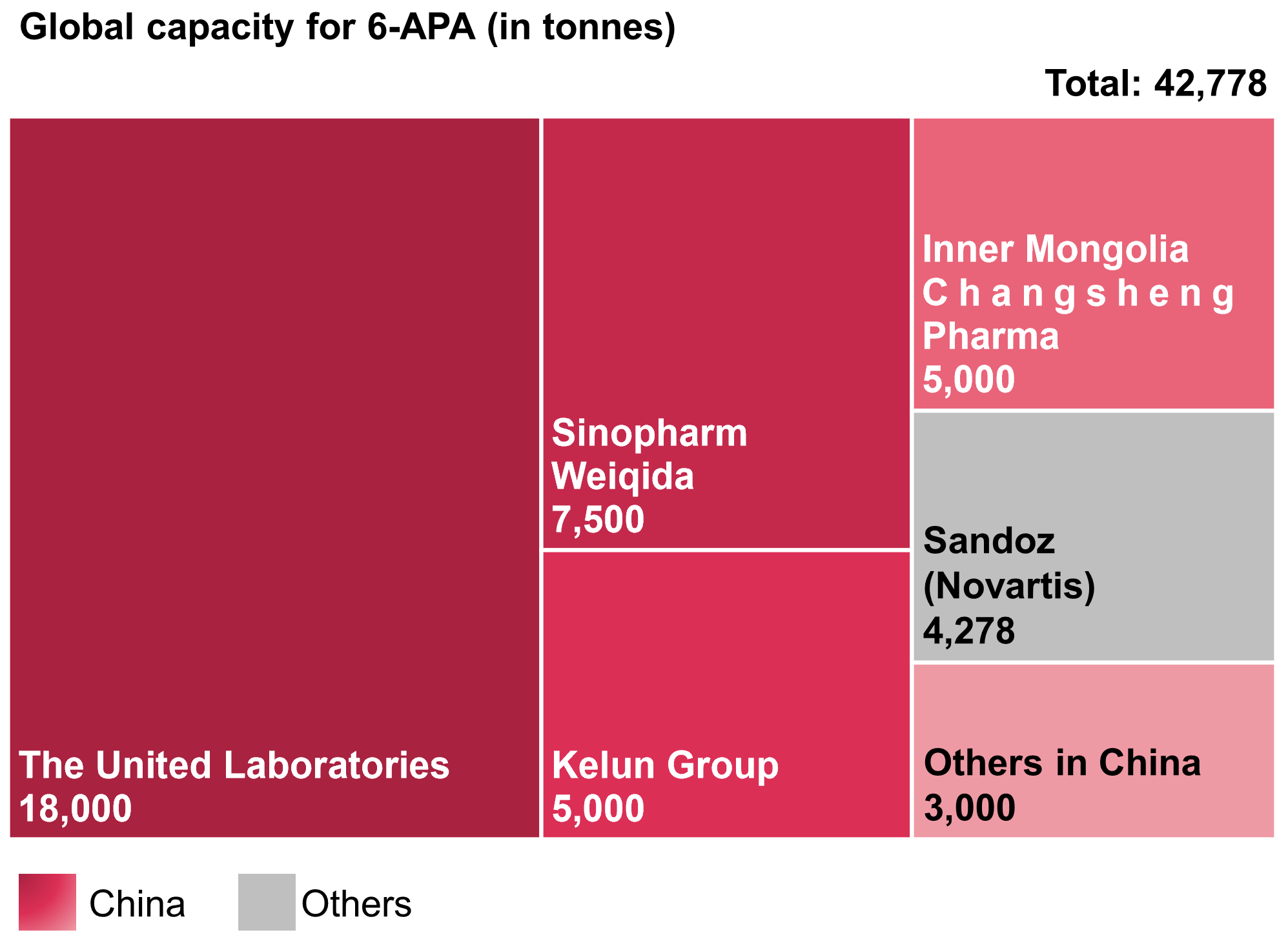

Similarly, certain pharmaceutical precursors have also become heavily concentrated in certain territories. For example, more than 90% of global capacity of a major precursor of penicillin antibiotics, 6-APA, is also located in China. Four players dominate the market. The single biggest plant outside of China is operated by Novartis in Austria, producing the precursor for captive consumption. The gradual relocation of capacity to China in recent decades was driven by production efficiency delivered by world-scale assets. As environmental regulations tighten and critical scale for economically feasible production increases, even former Chinese industry leaders are withdrawing from the business. Yet there are no mid-sized suppliers to provide an alternative for pharma buyers. This is an obvious case for downstream users to rethink their exposure to an overly concentrated supply market. While such cases of precursors are often less transparent than the globally known products in the global capacity graphic above, this is in fact where the greatest vulnerabilities for many global supply chains lie.

Three pillars: diversification, collaboration and trade

There is a valid case for the diversification of value chains that are at risk of disruption because of highly concentrated supply, or because they have become so long and dispersed that logistics and a lack of transparency have become a concern. Diversification of supply sources also mitigates risks from export bans, trade conflicts or disruptions caused by shocks like COVID-19. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean repatriation of production.

Truly local value chains require multiple production steps, resources, technology, funding, functional transport and service ecosystems, and sizable local demand to allow for scale. In many parts of the world, a local chemical industry is simply infeasible, as most countries lack the capabilities needed, the demand or both. Sub-scale production clusters often end up being shielded from competition through import tariffs or local content rules, relying on local regulation, funded through subsidies by the taxpayer and rising consumer prices.

Diversification means finding alternative and efficient supply sources and creating higher flexibility, rather than simply “repatriation”, so enabling value chains to be both more resilient to shocks and efficient enough to provide the world’s chemicals at an accessible price.

The COVID-19 crisis has also demonstrated how collaboration in international value chains can drive value instead of risks. For instance, the Indian chemical and pharmaceutical company Jubilant is one of six companies that helped scale up production of the drug Remdesivir for the US company Gilead Sciences in just three months. Through cross-industry collaboration and expertise-sharing, the companies managed to rapidly bring the drug to market to help treat COVID-19 patients. Such examples are an opportunity for the industry to demonstrate the value of international collaboration and trade as an enabler of efficiency, growth and resilience at the scale the world needs to solve its most pressing issues.

What is the World Economic Forum doing on trade facilitation?

Above all, all economic sectors require a functional global trade system. One over which the flow of chemicals and materials continues to deliver the essential ingredients and the protective properties that support societal resilience. As trade and investment decisions continue to become more political, and many value chains will become more regional, frameworks of international collaboration that support a trade system that is open, fair and based on clear rules for all stakeholders need to be protected to ensure access, and to promote resilience for the sector, for its constituting countries and for society in general.

This blog was written with contributions from Simonetta Rima (World Economic Forum), Simone Paes (Accenture), David Apel (Accenture) and Bernd Elser (Accenture)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Chemical and Advanced Materials

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.