Here’s a simple and fair way to end corporate tax abuse

Global losses from tax abuses amount to hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

Image: Scot Goodhart/Unsplash

Stay up to date:

Taxes

- Current proposals to tackle tax abuse are complex and unequal.

- A minimum effective tax rate will reallocate undertaxed profits with substantial benefits for non tax-havens.

- With a single rule for all countries and multinationals, there is no need for treaty changes.

The global losses from multinational companies’ tax abuses amount to hundreds of billions of dollars a year – revenues that are badly needed as the costs of the pandemic mount up. But international reform efforts have stalled and some future consensus seems unlikely.

Current OECD proposals are complex and unequal, and the only certainty is that they would deliver little extra revenue. Our proposal is simpler, more equitable and would generate much higher revenues. And on top of that, it could be introduced by a coalition of willing states, without requiring global agreement or treaty changes.

The current OECD process began in 2019 with great promise. The original BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) initiative that ran from 2013-2015 was the last great attempt to defend the arm’s length principle, which seeks to allocate taxable profit within multinational groups as if the individual subsidiaries were trading with each other at market prices. The realization that a more fundamental rethink was needed led to the renewal of negotiations.

BEPS 2.0 therefore took two starting points that broke with its predecessor – and these formed the two pillars of the approach. Pillar 1 addressed the ease of profit shifting, committing to go beyond both the arm’s length principle and the traditional "permanent establishment" definition, thereby apportioning at least some of multinationals’ global profits according to where their real economic activity took place. Pillar 2 addressed the incentives for profit shifting, by proposing a global minimum tax to put a limit on the race to the bottom.

Despite this promising start, however, the negotiations have lost their way. Both pillars 1 and 2 are widely seen to be excessively complex, with the revenue impacts highly uncertain and any benefits limited at best – even for OECD members. Lower-income countries have expressed frustration at being ignored, and most modelling suggests trivial benefits if any, especially under pillar 1. Unsurprisingly, there has been little appetite to push ahead.

Pillar 1 seems doomed, with no consensus even among OECD members on whether it should cover only highly digitalized companies or a wider group of large multinationals. The new Biden-Harris administration, however, has joined with many EU countries in committing to pursue a global minimum tax.

Here, in pillar 2, the problems stem largely from the unwieldy proposal. This includes separate measures for home (residence) and host (source) countries to apply top-up taxes, with a complex system of rules to manage the interaction of these rights. The granting of superior rights to the home countries of multinational companies (MNEs) would particularly disadvantage lower-income countries, which more often are host to MNEs. To remedy this, the OECD proposes a third rule allowing source country taxation, but this would require the tax havens that benefit most from profit shifting to accept disadvantageous revisions to their tax treaties. This would give them an effective veto, cause endless delay, and has little chance of success.

This is where our proposal for a minimum effective tax rate, METR, could provide a way forward. Like the OECD proposal, we identify the share of each multinational’s global profits that are undertaxed. Then, avoiding any disadvantage to lower-income countries, METR reallocates these undertaxed profits among all countries where the MNE has a taxable presence, to allow each such country to apply its own taxation under its own rules and rates.

By reallocating this undertaxed profit in proportion to the location of multinationals’ real economic activity, including the location of sales, we are able to combine the benefits of pillars 1 and 2: placing profits in market countries at the same time as the incentive to profit shift is reduced or eliminated. And because the METR is effectively a combination of two rules (for income inclusion and undertaxed payments) which the OECD has found could be applied under national tax rules, the METR would not require treaty changes. (To account for market and other countries where an MNE maintains no taxable presence, a “throw-back” rule would prevent relevant profits from going untaxed.)

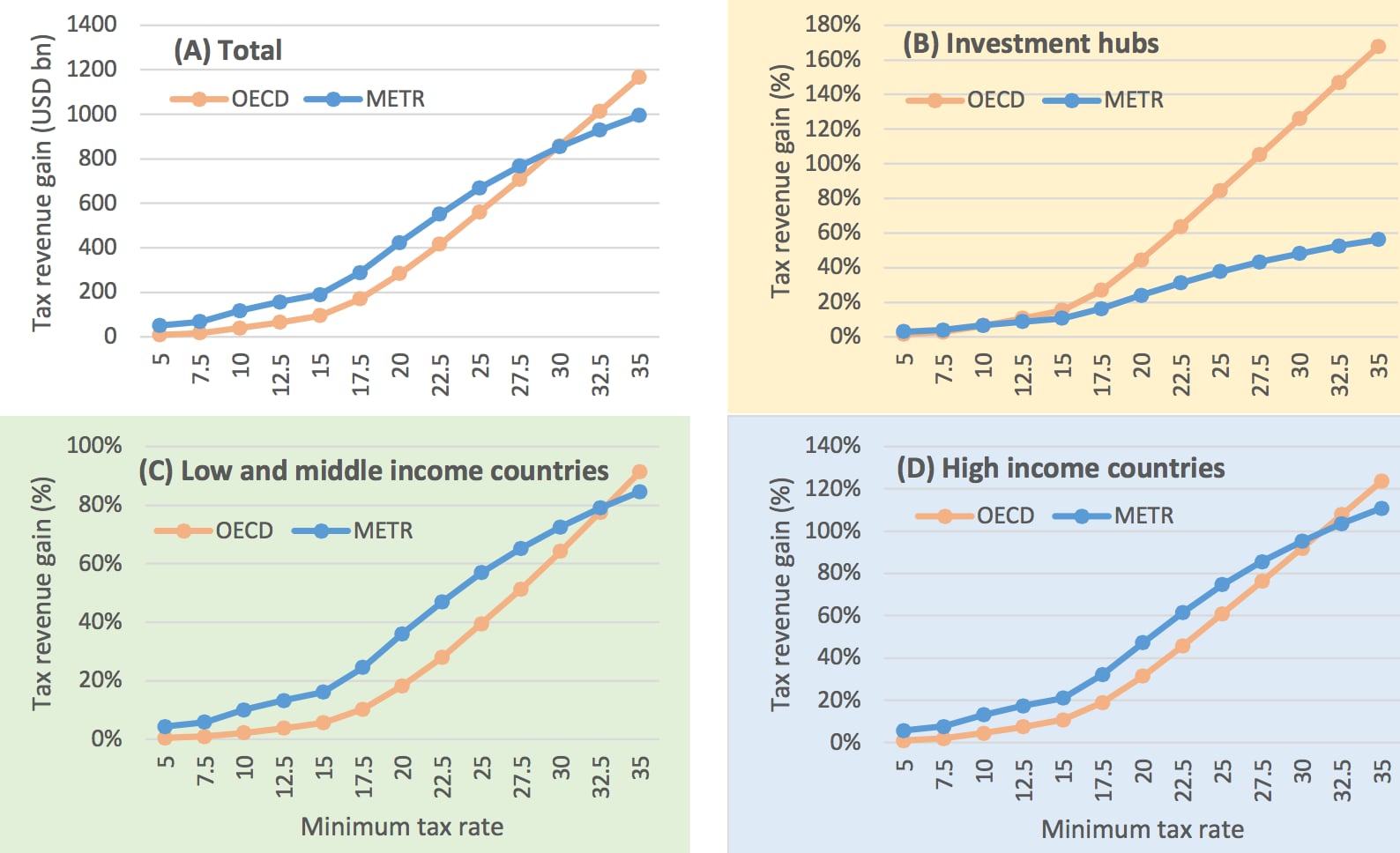

We have modelled the METR, based on the OECD’s economic impact assessment of the blueprint, to ensure that our findings are as closely comparable as possible. The METR is estimated to generate higher overall revenue gains at all levels of minimum tax rate up to 30%, ranging from $50 billion to $140 billion in additional revenue gains. This is because the METR allows each country to which undertaxed profits are allocated to apply its own tax rate, while the OECD proposal allocates a top-up tax to bring the rate on undertaxed profits up to only the set minimum.

(A) Total tax revenue gains. Relative tax revenue gain for (B) Investment Hubs (C) Low and middle income countries, and (D) High income countries. Relative gains are calculated as an increase from current tax revenue. The METR proposal (blue) and OECD proposal (orange).

The distributional differences are even more striking. The METR would provide investment hubs (the OECD’s euphemism for the main corporate tax havens) with smaller increases in revenues than other countries, and smaller increases than the OECD proposal (panel B). Importantly, the additional revenue gains are relatively higher for low and middle-income countries (panel C) than for high-income countries (panel D), and would bring them more absolute revenue gains than the OECD proposal. The more equitable reallocation of taxing rights in the METR proposal is especially relevant if profit shifting is not eliminated by the minimum tax rate – i.e. if the minimum tax rate is too low.

What's the World Economic Forum doing about tax?

With substantial benefits for most non-havens, including countries at all income levels, the METR has the important attraction of political feasibility. It offers a simple, single rule for all countries and all multinationals, and with no need for treaty changes. The METR is fairer between countries, because the rights to tax undertaxed profits are allocated based on real activities in each country; and fairer between companies, because countries apply their standard tax rate to their allocation of undertaxed profits.

The METR does not offer the complete elimination of revenue losses due to corporate tax abuse. What it does provide, however, is the promise of substantial new revenues at a time these are urgently needed, and in a globally progressive way.

The METR proposal was published by Tax Notes International. A full-length version with more detailed modelling is available for download. This post and the full proposal were authored by Sol Picciotto, Jeffery M. Kadet, Alex Cobham, Tommaso Faccio, Javier Garcia-Bernardo, and Petr Janský. Alex Cobham is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on the New Agenda for Fiscal and Monetary Policy.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Aengus Collins

July 15, 2025

Guy Miller

July 15, 2025

Aaron Sherwood

July 15, 2025

Heba Chehade and Rene Rohrbeck

July 15, 2025

Danny Rimer

July 14, 2025

Silja Baller and Fernando Alonso Perez-Chao

July 11, 2025