Valuing natural capital is key to the future of investment. Here's why

Image: Unsplash.

Stay up to date:

Institutional Investors

- A multi-trillion-dollar annual investment gap needs to be filled to meet decarbonization goals and the transition to a circular economy.

- Decarbonization and circular economy transition pathways will change long-term market assumptions and financial return expectations.

- The investment portfolio of 2040 will strengthen demand for natural capital.

This piece is from a blog series written by members of the Global Future Council on Investing exploring factors shaping the investment portfolio of 2040.

As the aphorism goes, the best way to predict the future is to create it. That is exactly what investment does – it allocates money now in the expectation of benefits in the future.

Yet as we look at the world’s long-term challenges, such as climate change, population growth, geopolitical instability and cyber-security, we currently face a challenge of under-investment. In fact, we are under-investing by trillions of dollars per year. This is undoubtedly a priority for policymakers and the investment industry.

As the investment industry directs funds into some of these long-term challenges, the question becomes what those transition pathways might look like. It is also critically important to think about how these pathways may change underlying market assumptions and expectations for financial returns.

Revisiting assumptions on financial and natural capital

Let’s start by looking back 250 years. To simplify things, let’s assume there are two types of capital: financial and natural. Most professional investors have spent their careers thinking solely about financial capital. It’s only recently that multiple stakeholders and multiple capitals have started to impact the investment mainstream.

However, 250 years ago, financial capital was very scarce and natural capital was abundant. Simple economics would predict strong returns for financial capital (scarce) and low returns on the abundant natural resources. Now, on the same basis, we’d expect returns on financial capital to be low now that it is abundant. Indeed, government bonds being issued at negative yields suggests that the “risk free” rate is low and not likely to increase in the immediate future.

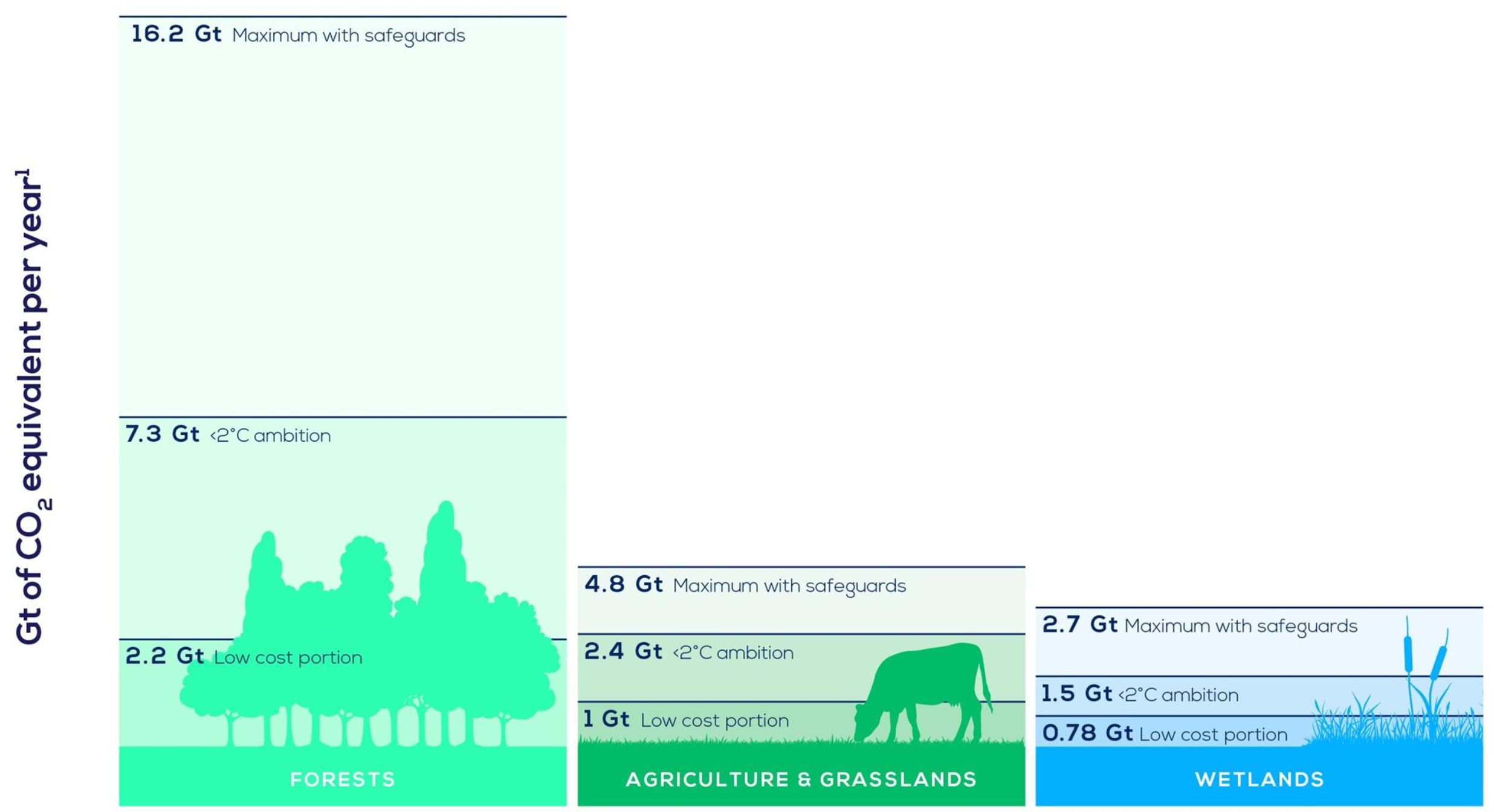

Looking ahead to the year 2040, what returns might we expect from natural capital now that it is scarce? During the next 20 years we will need to feed an additional 1.4 billion people. The earth will be hotter. Liveable and farmable land (in some parts of the world) will be lost. We should be preserving, if not expanding, our forests.

A consensus appears to be emerging regarding this change in the relationship between natural and financial capital. Recently, a global group of 29 ESG and sustainability investment specialists were surveyed on the macro landscape of 2040. Their insights were revealing.

Given that investment is an endeavour where 55% is considered a strong signal, the results suggest investors may need to adapt their portfolios. If we proxy natural capital by land, there appears to be strong demand for it (and its services) during the next 20 years. It’s elemental. Scarce capital, with strong demand can yield attractive financial returns. Mark Twain was ahead of his time when he said, “buy land, they’re not making it anymore” (well, not at scale).

Lessons in demand from the clean energy transition

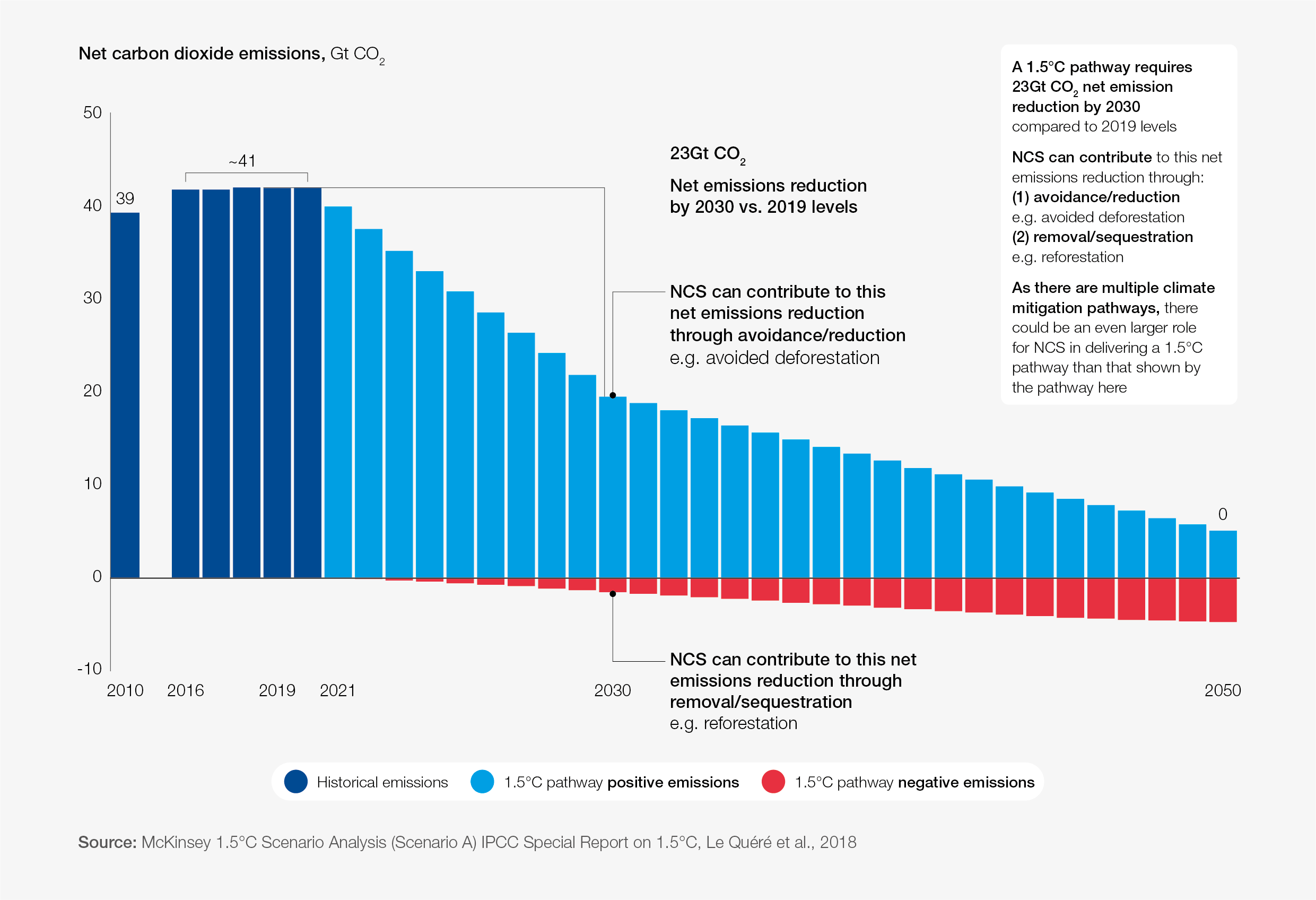

Looking at the clean energy transition provides further insights. As we collectively seek to adapt the global economy, the scientific consensus is that we will need to have completed our second halving of emissions by 2040. Let that thought sink in. The global economy needs to reduce its emissions from the current level of 54 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent to no more than 13.5 billion tonnes by 2040. The scale of the required transition is hard to imagine.

Successfully meeting our decarbonization goal by 2040 would mean the world has made considerable progress in converting its energy supply to renewables. In fact, by 2040, having spent $87 trillion, the world might be about two-thirds of the way through the energy transition programme.

This represents both good and bad news. The good news is that this represents a copious supply of assets that can absorb all those defined contribution pension contributions. The bad news is that these high-quality, carbon-free electricity investment products will most assuredly have strong demand and are sure to be bid up in price with the result being low investment returns.

The large asset owners I have informally spoken to all make this point – they believe the returns will be low. In the short term, while governments seek to repair their finances post-COVID, a mental switch is needed to consider electricity generation from renewables as a new risk-free asset. As a risk-free asset we should be comforted by its low returns. Over the longer term, we might expect pricing, and therefore returns, to adjust.

However, as identified by Johan Rockström, carbon in the atmosphere is just one of the nine planetary boundaries needing to be managed. Our bigger problem is that our linear economic system (take-make-use-throw) isn’t sustainable over the long-term on a finite planet.

What is the World Economic Forum doing on natural climate solutions?

By definition, a circular economy is about disrupting, or replacing, the linear economy. That means the through-put of consumer goods will need to be reduced considerably. While there is considerable uncertainty regarding the form and function of a circular economy, at first sight it appears to represent a massive reshaping of the opportunity set for the investment industry (more microfinance of local business perhaps?).

As it relates to the 2040 investment portfolio, the relevant question is whether this matters within the 20 year timeframe we are considering. Building the 2040 portfolio will probably require looking out to at least the year 2050. Will we have started to transition to a circular economy within that time? If we have, then we need to add yet more profound change on top of our climate transition.

Where can we place our abundant financial capital?

While I am happy to assert that financial capital is abundant today, if the investment industry plays its part in the transition and converts each year, say, $1 trillion of cash into long-term assets, then we will quickly change the supply/demand balance for financial capital.

Are there additional factors to consider in looking ahead to 2040? Absolutely. What also needs to be considered is the likely shape of government finances 20 years into the future as well as shifting demographics (the ‘gravity’ of economics), geopolitics, and technology. And we have not overtly considered the functioning and evolution of the overall economic system.

To properly explore the possible landscape of 2040, we would need to consider all these issues, their inter-relationships, and concepts such as path dependency and non-linearity – and that requires more than a blog post.

The future is impossible to forecast. But that doesn’t mean we can’t build the world we want. I believe the investment industry can strongly influence how the world changes. We should grasp that opportunity with both hands.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Michelle You

April 10, 2025

Andrea Willige

April 10, 2025

Angie Farrag-Thibault and Natacha Stamatiou

April 9, 2025

Michael Atkinson and Andrea Willige

April 9, 2025