Why wetlands are a versatile climate and biodiversity hack

A glossy ibis in the Ammiq wetland in Lebanon. Image: Reuters/Ali Hashisho

- The potential of wetlands to mitigate climate change and extreme weather events has been neglected.

- More than a third of global wetlands have disappeared since the 1970s.

- Quantified targets are needed for policy-makers to protect wetlands.

What’s the best and cheapest way to harness nature for fighting climate change? Answer: protect and restore the world’s wetlands – its bogs and lakes, mangroves and mires, peatlands and rivers, tidal mudflats, and floodplain marshes.

What’s the best way to counter extreme floods and droughts in a rapidly warming world? Protecting and restoring wetlands.

Which biodiverse ecosystems are disappearing faster than forests, but so far have received little attention from the Convention on Biological Diversity? You guessed it: wetlands again.

The many ecological benefits provided by the world’s wet places are too often neglected in discussions about both climate change and biodiversity protection – by scientists, conservationists and policy-makers alike. As a result, from the mangroves of South-East Asia to the marshlands of South America and the swamps of Central Africa, they continued to be drained and dammed with impunity.

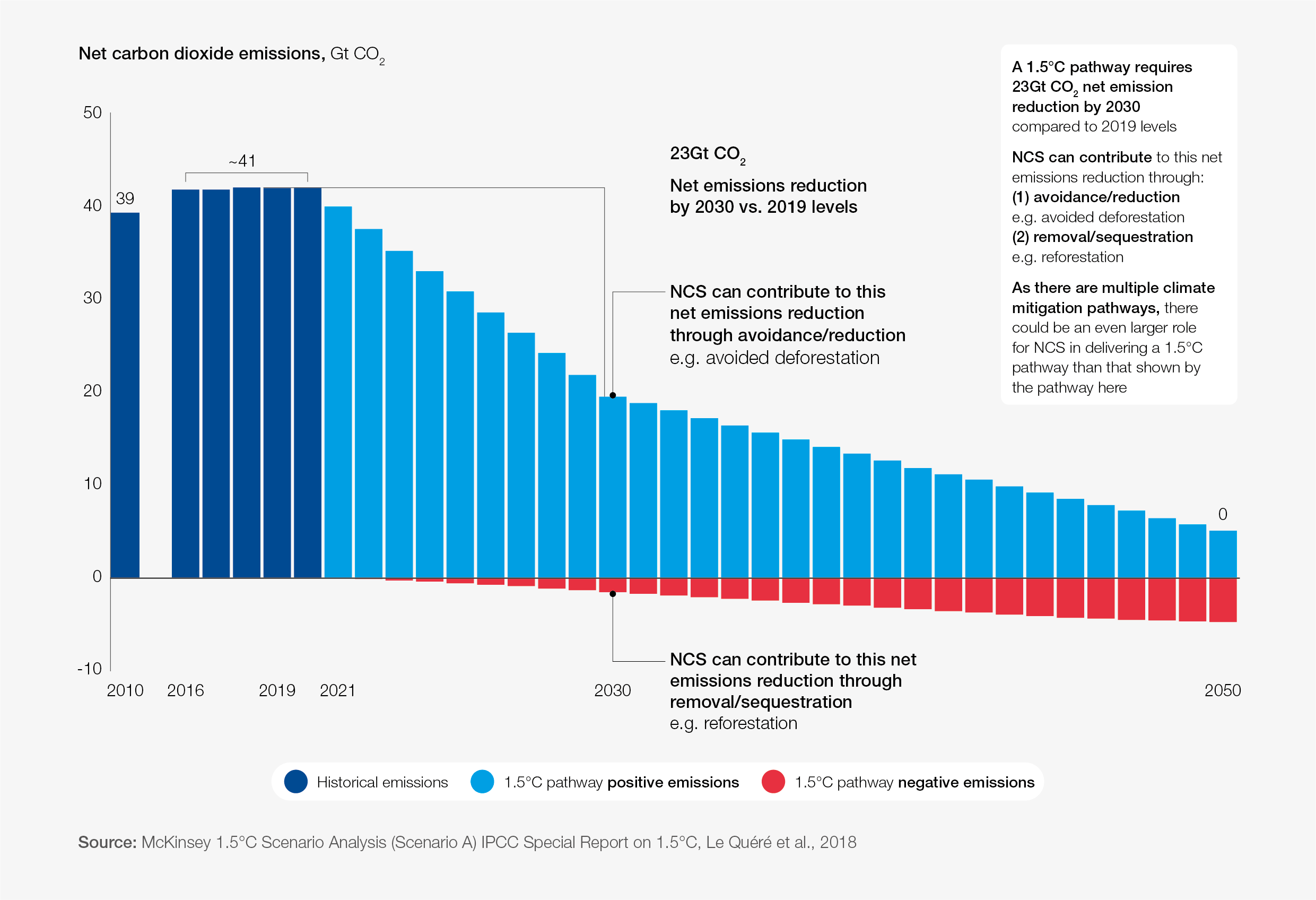

At the recent Glasgow climate conference, nations lined up to pledge an end to deforestation and to start restoring forests. But there were few equivalent promises for ending wetland loss, or re-wetting drained land, even though wetlands are extremely important natural carbon stores.

Much the same has been happening at the latest negotiations in Geneva for the post-2020 global Biodiversity Framework under the Convention on Biological Diversity – even though wetlands contain more biodiversity than forests, holding 40% of the planet’s species on just 7% of the land.

By some measures, the world has already lost more than 80% of its former wetlands, more than a third disappearing since 1970. That is a faster rate than for any other major ecosystem. Drains and dams have done far more damage to nature than chainsaws.

Without far more attention to protecting and restoring the world’s wet places, we have little chance of meeting our climate or biodiversity goals. Yet they remain Cinderellas at the conservation ball.

Hectare for hectare, coastal mangroves store four times more carbon than neighbouring rainforests. The continued drainage of peatlands alone is responsible for more than 5% of global carbon emissions. But their importance extends far beyond carbon capture.

The recent IPCC report on the impacts of climate change highlighted the vulnerability of ecosystems such as wetlands to high temperatures, fires and drought, and warned that their loss will amplify climate change by releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases. But it had much less to say about the vital role that wetlands can play in protecting humans and wildlife from climate change.

Wetlands act as sponges that ameliorate droughts by storing water and releasing it to maintain river flows long after the rains cease. And they protect against floods, too. When more than 200 people drowned as rivers overflowed in north-west Germany in July 2021, intense rainfall from climate change got the blame. Few noticed the role of drains installed in moorlands upstream in recent years that had destroyed their ability to soak up the rain, which instead poured off the land into rivers within seconds.

Wetlands also protect against wildfires. In the heart of South America, a quarter of the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland, burned during 2020; most fires broke out in the north, the areas where farmers have been encroaching.

Restoring lost wetlands is vital to stemming the cost of climate disasters. After the 2021 floods, the Germany government set aside €30 billion to repair the damage. But without repairing the sponges too, there will be many more such floods.

Some countries have caught on. Indonesia intends to block drains to re-wet 2.5 million hectares of dried peatlands and to bring back 600,000 hectares of mangroves, cleared for coastal prawn farms. We are working with African governments to restore a million hectares of mangroves, to protect shorelines from storms and rising tides.

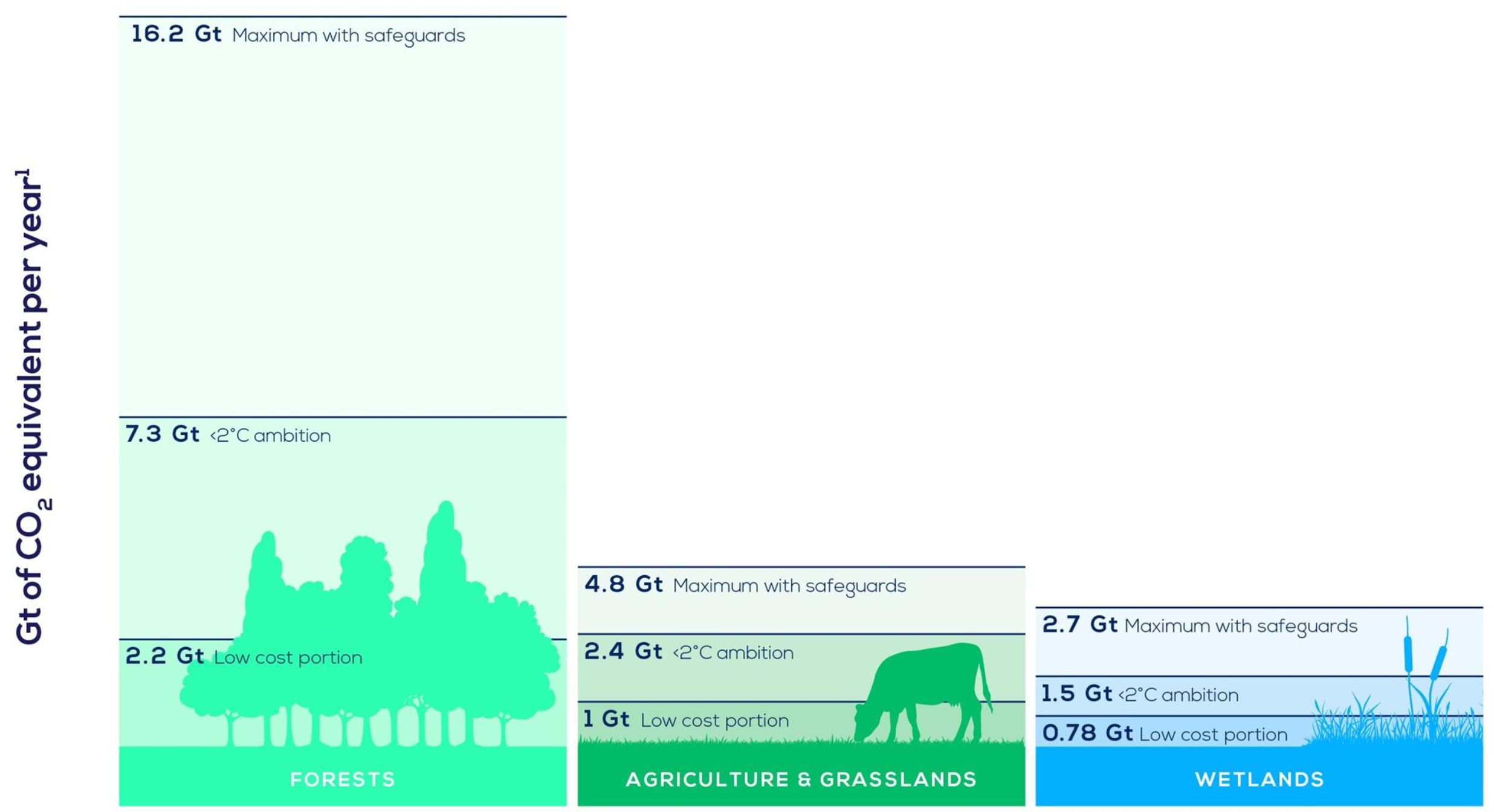

The science is clear that wetlands are effective natural solutions for a range of global problems. And restoration by blocking drains or removing obstacles to natural regeneration is often cheap. What is missing are quantified targets to galvanise policy-makers and hold them to account.

We propose a minimum of 30% of surviving wetlands be put under formal management for conservation, and that planning systems ensure that all existing intact and wilderness wetlands are retained, while all others are managed with their biodiversity value to the fore.

In addition, we propose that at least 20% of wetlands already degraded by human activity should be restored by 2030. That should include at least 10 million hectares of peatland and a 20% gain in mangrove cover. Tidal flats should be increased by at least 10% by removing sea walls, and at least half of the 7,000 wetland sites identified as critical to migrating birds should be managed with their needs as a priority.

Finally, we need protection and restoration of water systems as a whole, not just specific wetlands. Rivers feed – and are fed by – wetlands all the way from their source to the ocean. They are connectors across landscapes, and sustain other ecosystems. Targets for protecting forests and oceans will fail if we don’t protect and restore wetlands.

So it is vital that all the world’s surviving free-flowing rivers should be protected from dams, levees and sand mining, and that, where possible, managed river flows mimic nature.

What is the World Economic Forum doing on natural climate solutions?

But beyond the targets, we need a mental reset. Most of us still have a strangely negative attitude to wetlands. We see them as dank badlands rather than rich ecosystems. Scary jungles got a 20th-century rebranding as magical rainforests; our bogs, mires and swamps need a similar 21st-century makeover. Our climate, our biodiversity and the safety and livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people depend on it.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Planet in focus: The technologies helping restore balance – and other news to watch in frontier tech

Jeremy Jurgens

November 13, 2025