This electric bike is on the road to being entirely fossil-free by 2025. Here’s how

Swedish energy company Vattenfall and electric bike maker CAKE are collaborating on a project to make a fossil free dirt bike.

Image: CAKE.

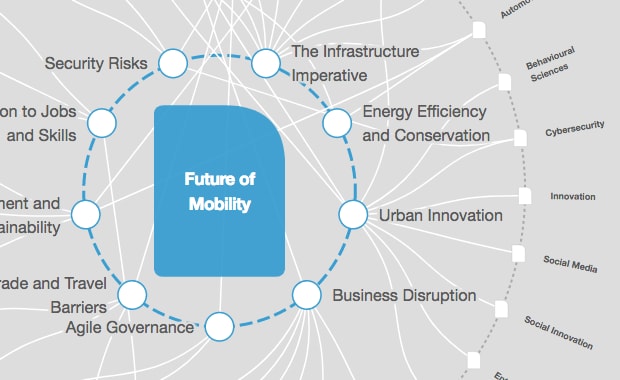

Explore and monitor how Mobility is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Stay up to date:

Mobility

Listen to the article

- Swedish energy company Vattenfall and electric bike maker CAKE are collaborating on a project to make a fossil free dirt bike.

- The bike’s current carbon footprint is calculated as 1,186kg CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) and the aim is to reach zero.

- Annika Ramsköld, Head of Sustainability at Vattenfall, Isabella Pehrsson, CAKE’s Head of Sustainability, and CAKE’s Founder and CEO, Stefan Ytterborn, explain what they’ve learned so far.

“It’s great if you drive an electric car or bike, but that’s not the full story,” Annika Ramsköld, Head of Sustainability at Swedish energy company Vattenfall, tells the World Economic Forum before she heads to Egypt for COP27.

As one of the founding members of the Forum’s First Movers Coalition - essentially a buyers’ club for low-carbon technology - Vattenfall is creating its own ecosystem of partners all with a single aim: to enable fossil free living within a generation.

One of those partners is Swedish electric motorbike company CAKE - and together they’re working on developing a fossil free dirt bike, the CAKE Kalk Off Road, by 2025.

When the bike’s on the road running on renewable electricity, its emissions are close to zero, but as much as 80% of its lifetime emissions come from just making the bike, from the production of the materials to their transportation and assembly.

The current carbon footprint of the bike is calculated as 1,186kg CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent), which is represented in the images above as the size of the cube in which the bike’s suspended. The aim is to reach zero and ultimately get rid of the cube.

To become fully fossil free, all the materials and components - from steel, to plastic, suspension and the battery - must be produced and transported without any fossil fuels or sources being used.

This is the ‘full story’ Ramsköld is referring to and it’s these emissions from the whole value chain that CAKE and Vattenfall are working to reduce - and then share their learnings with others.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

“It's not about one product, one bike becoming zero. It's about every product out there,” says Isabella Pehrsson, CAKE’s Head of Sustainability. “That's where we have to scale. So if we can inspire people to get started, even if every product out there would halve their emissions, we will come a long, long way.”

Here, in an edited interview, Ramsköld and Pehrsson, along with CAKE’s Founder and CEO, Stefan Ytterborn, explain what’s involved in going fossil free.

What's the World Economic Forum doing about the transition to clean energy?

How did the CAKE and Vattenfall collaboration come about?

Ramsköld: “As happens very often, you see that you want to make a change - and then stars start to align. We both have the ambition to decarbonize the full value chains and we are frustrated that the speed is too slow. So everything at the heart of this collaboration is about speeding up, inspiring others to really start acting here and now because we cannot wait.

“At Vattenfall, we produce a lot of renewable energy and that in itself is good. However, we do have a footprint from our supply chain when wind turbines and solar panels are produced. It's easier to tackle your own emissions, but to tackle the whole supply chain, we need to collaborate. We know that a big chunk of the carbon footprint often comes from components like steel, aluminium, cement as well as from transport and we must find ways to reduce that. Whatever we do in this collaboration clearly can benefit other industries.”

“Everything at the heart of this collaboration is about speeding up, inspiring others to really start acting here and now because we cannot wait.” - Annika Ramsköld.

Ytterborn: “It’s a dream project and it makes sense to connect the tiny start-up CAKE, trying to change the world by using motorcycles as our tool, and the big giant in need of change. We’re trying to analyse the whole value chain, and embrace the complexity with a holistic approach to see what we can achieve by doing it by the book. But we would never, ever have been able to go to those depths without the resources of Vattenfall. So we’re excited and overwhelmed by the opportunity of working with them and inspiring the industry as a whole through sharing our success and our shortcomings as an open source.”

How did you go about measuring the bike’s carbon footprint?

Pehrsson: “We took the bike apart and we had 100 parts made up of 2,000 smaller components. We worked out the carbon footprint for every component using an LCA (life cycle assessment). But we want to highlight the discussion around LCA. The current independent LCAs can be performed to anyone’s benefit, within the system. The topic of using recycling content is one that is highly debated, in terms of calculation. This is why we have publically released our methodology that follows the ISO 14040/44 standard for everyone to understand our standpoint on LCA, which is to calculate in the strictest possible way. Our system boundary includes every single material, process and transportation throughout the complete value chain and that’s why we cannot reach all the way to zero, as offsetting is not allowed within the project.”

Will the cube ever be smaller than the bike itself?

Ytterborn: “To be honest, we don’t know that yet. We know from day one that of course we'll never get to 100% fossil free by 2025. It's impossible in that time-frame to decarbonize the entire supply chain. We are talking about tyres, about semiconductors, about battery cells and working with collaborating partners putting a lot of resources into making them better.”

Pehrsson: “The promise that we can be very confident in is that the bike will represent the cleanest possible bike in 2025. Then the bigger perspective is why is the money in the wrong place on this planet? Why is there a lack of solutions? We're still investing in oil, for example, why isn’t that invested in clean energy, to help decarbonize more industries in more countries?”

Have there been any lightbulb moments on the project?

Pehrsson: “At first we said let's go and find partners to decarbonize each of those 100 parts, and evaluate them on how much they're willing to invest and the tech they have. But it wouldn't have been the best solution. Then we realized the emissions for those parts mainly come from the material, and they happen to share four materials between them. So if we can decarbonize the material, like fossil free steel, aluminium, plastic and rubber, we only have to do it with four suppliers. Then we will nominate the material for the part processor, which can be more local, we can control it, and to decarbonize a processor you basically decarbonize the building. That was a major learning.”

What about using recycled materials for the fossil free electric bike?

Pehrsson: “At first we thought we wouldn’t use them because the world will need more material going forward and we wanted to focus on the way we do virgin material, like fossil free steel. Then we got input from LCA researchers that, yes, in one way that makes sense, but we also need to find a way to decarbonize recycled content and use it to a much bigger extent than is used today. And also with the time horizon that we have, that is the option available to us, because it's just three years away. But we need to think whether recycled content comes in the right qualities. Take recycled aluminium: should we degrade the quality and then have to make a thicker bike just so we can use recycled content? Or should we change the system of recycled content so it can push through higher grades?”

Ytterborn: “This is one of the key aspects where we can drive change. Because if we could develop the industry towards recycling different grades and qualities of aluminium, making sure that the right quality ends up in the same bucket when it's being melted and recycled, we would keep the quality standard. The price of aluminium depends on what it was graded on an index from 10 to 1,000. And when everything is melted together, the way it's being done today, it ends up being a 10. So we need to find the system to stick to the same quality material that has been initially processed for certain functionality or purpose. It would be extremely interesting to understand how much high-quality metal is actually orbiting around Earth. It would be tons and tons, worth billions.”

Will your findings change the way the bike is designed in future?

Ytterborn: “I think we will start designing something that will look totally different, because we will be adapting all our learnings into something with consequences for the design and engineering. So it's going to be a totally different beast, in terms of how it appears, after this process.”

Pehrsson: “Everything starts with design. We are trying to find materials that fit a certain design, instead of letting the sustainable materials of the future influence the design. And that will be a big area.”

What does Vattenfall hope to achieve from the collaboration?

Ramsköld: “What is unique and very important is that we really looked at every nitty-gritty component, all the different types of materials that are there. And I think whatever learnings we get from that one connection with a company that can produce fossil free plastics or fossil free steel or fossil free aluminium, anything we do there, we can then multiply that into other value chains, be it for wind turbines or pumps or whatever. And all the learnings here will be able to speed up the transformation in other supply chains as well.

“I actually use the CAKE example when I have dialogues with other suppliers where we want to put requirements on the supplier we have our contract with, but also understand the full value chain. What are the different components you have? How can we contribute? We use this as a model to say, but where do you have your key suppliers? How can we jointly ensure that we help them to decarbonize? And what type of requirements do we need to put in there? What type of knowledge can we share to make things happen? So this approach of really looking at everything from the raw material until it becomes a product, and then also end-of-life, to have that way of looking, is really helping us to have a qualitative discussion with every supplier.”

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Energy TransitionSee all

Michael Wang

July 28, 2025

Ayla Majid

July 24, 2025

Manikanta Naik and Murali Subramanian

July 23, 2025

Arunabha Ghosh and Jane Nelson

July 22, 2025

Ali Alwaleed Al-Thani and Santiago Banales

July 21, 2025

Goodness Esom

July 18, 2025