Trucking needs to U-turn on its carbon emissions - here’s how

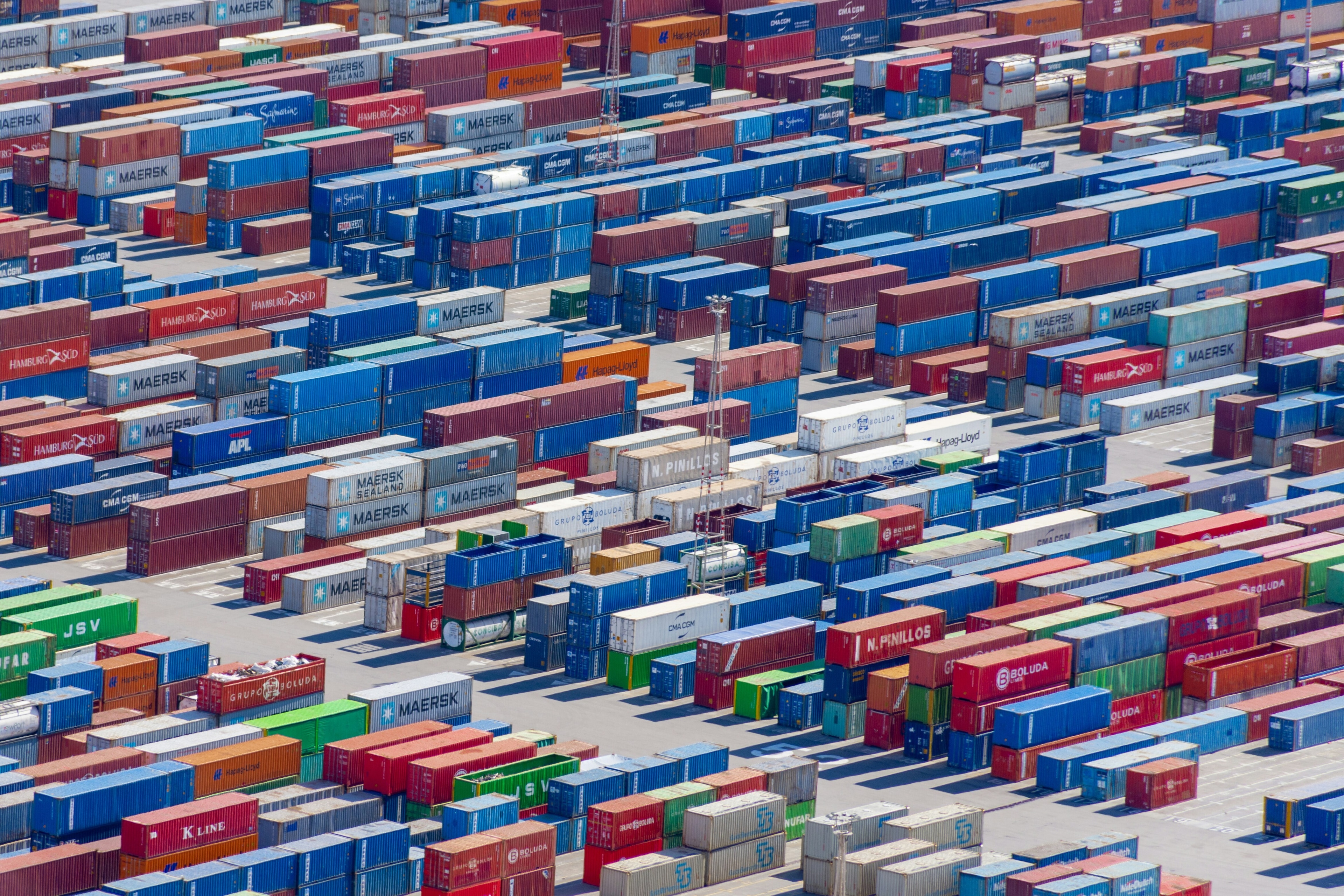

We have to find a way of transitioning to zero-emission trucks, and fast. Image: Unsplash/Gabriel Santos

- Road freight contributes 15% of Europe's CO2 emissions, but Cemex is collaborating with manufacturers on new all-electric, ready-mix concrete trucks, it says.

- Battery-electric and hydrogen technologies are accelerating, but there are some tough nuts to crack with gross weight, cost and charging infrastructure.

- A lack of charging and refuelling infrastructure is a hurdle to overcome as the price tag of including this infrastructure in Europe can be up to $42 million.

Trucks are a vital part of today’s global economy. They transport three-fourths of the freight moving through the U.S. and European Union. They also have an outsize impact on the health of our communities and our planet.

In Europe, road freight generates 15 percent of all the continent’s CO2 emissions. Most of this comes from medium- and heavy-duty trucking — the vehicles whose emissions are hardest to abate. In the U.S., such trucks make up only 8 percent of all vehicles, but emit one-third of on-road greenhouse gases and around two-thirds of all vehicle emissions of nitrogen oxide and particulate matter (PM2.5) — two substances affecting human health. We have to find a way of transitioning to zero-emission trucks, and fast. No speed limits or rest breaks for this ambition.

Electrifying the power train is the way ahead, especially for medium-sized trucks. For heavy-duty trucks, solutions such as hydrogen and fuel cells look promising. The good news is that battery-electric and hydrogen technologies are accelerating at speeds more akin to a Ferrari than a six-axle semi. But there are still three tough nuts to crack: total gross weight; cost; and charging infrastructure. This article looks at how to get it done.

Watch your weight

All truckers know they must watch their weight, and we’re not talking waistlines. For most short-haul, medium-duty trucking, battery-electric vehicles are rapidly becoming as cost-competitive as their diesel brothers. The problem is, the heavier the truck, the bigger the battery needed to shift it. And given that every truck has a fixed total weight it cannot exceed, the bigger the battery, the less of a payload the truck can carry.

The cement and concrete industry is a good example of a sector where both weight and time are critical. Concrete is a very heavy as well as perishable material that must be delivered in a truck with a rotating drum to avoid it hardening. The truck’s mission is to deliver the material to the doorstep of a construction site, often in an urban area, within no more than two or three hours of departure.

Electrifying the transport of such a heavy material is one of the toughest tasks in trucking’s quest to lighten its carbon footprint. It’s a challenge that’s been taken up by Cemex, the largest ready-mix concrete manufacturer in the western world. Cemex recently commissioned 10 new battery-electric ready-mix trucks. These are heavy-duty units that typically deliver 20 metric tons of concrete three or four times a day.

'It’s a bit like doing a U-turn up a one-way street in a 16-wheeler. But if anyone can do it, a trucker can.'

”To shift this amount of weight in a zero-emission way currently requires a battery weighing two metric tons. That’s an issue, because urban authorities set strict rules on the total gross weight of trucks and their loads, to protect bridges and road surfaces from damage. So to electrify its fleet means Cemex loses two metric tons of concrete per delivery, or 10 percent of its payload. With a fleet of over 10,000 mixers, that’s a lot of concrete to leave behind, especially in a sector such as building materials which operates on high volumes and low margins.

So why not stick with diesel mixers? There are three compelling reasons: cost; health; and climate change.

More cities are introducing low-emission zones (LEZs) to penalize heavy-emitting vehicles from entering the city limits. London, for example, has set its highest penalty for trucks weighing over 3.5 metric tons that don’t meet the standard at $2,450 per day. The motivation for LEZs is more about human health than the climate. But health is a compelling reason in its own right. According to one "conservative estimate," vehicle exhaust emissions caused 385,000 premature deaths worldwide in 2015 — half due to diesel. In the U.S., reductions from vehicle emissions over the decade to 2017 yielded $270 billion in social benefits, according to the Harvard School of Public Health. And then, of course, there is the impact on climate change.

Costs fall if demand rises

Companies such as Cemex are motivated to act by all these reasons. But as a founding member of the World Economic Forum’s First Movers Coalition, Cemex is making this investment to send a signal to manufacturers that there is a market for zero-emission heavy-duty trucks. The hope is that if demand rises, costs — and battery weights — will fall, as the technology improves and scales. And they need to fall: Cemex has paid a premium of three to four times the cost of a regular diesel truck for each of its all-electric, ready-mix concrete trucks.

The private sector has proposed some financing solutions to ease the pain on the CapEx side. Vehicle and battery leasing models may offer a solution, especially for a fast-developing technology where the residual value of an asset at the end of its useful life is uncertain. However, there’s a clear role for public sector incentives, too. While most of us tolerate the stick of regulation — whether it’s LEZs or emissions standards — for the sake of the greater good, it would help to have a carrot too.

In fact, forget the carrots — make that a double Whopper with fries. California is leading the way with its Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project (HVIP). The way it works is simple and effective. The state government announces the maximum amount of cash available each year, sets the level of subsidy across scores of eligible vehicles, then issues point-of-sale vouchers on a first-come, first-served basis until the money runs out.

For a heavy-duty, zero-emission tractor such as Daimler’s new battery-powered Class 8 Freightliner, HVIP’s subsidy is $120,000. In 2021, the scheme attracted $240 million worth of requests. Since its inception in 2009, the initiative has funded over 9,000 clean vehicles in California. HVIP currently has 1,200 zero-emission truck (ZET) orders pending — roughly double the current deployment of ZETs in the state. So you get an idea of how fast this is accelerating.

Charging and refueling will be the bottleneck

Charging is the third — and arguably the hardest — nut to crack when it comes to vehicle electrification. "Vehicles will not be the bottleneck," says the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA). What will be is a lack of charging and refueling infrastructure.

Charging electric trucks faces several challenges, including location of the infrastructure, recharge speeds and ensuring sufficient renewables to deliver the clean power required. Location comes down to a choice between depot and roadside. The former is currently the only option for heavy-duty trucks. For example, it takes six to eight hours for Cemex to recharge its electric mixers, so that can only happen overnight in its depots.

The roadside charging option is needed for long-haul road freight beyond a range of about 249 miles. Governments are promoting the idea of "green corridors," featuring not only roadside charging stations but also electrified highways — similar to train and tram lines — with trials planned in, among other countries, Sweden and the U.K. Another option is for heavy-duty trucks to swap out exhausted battery packs or entire electric tractors at strategically positioned stops along their way — harking back to the days of the stage coach with its hunger for fresh horsepower.

Refueling infrastructure is also needed, because the alternative to battery-electric trucks is a fuel-cell electric vehicle powered by green hydrogen. This has often been heralded as the solution for long-haul and heavy-duty trucking, where the weight of batteries and the time taken to recharge them are major constraints. However, although there is a handful of hydrogen-powered trucks on European and U.S. roads, commercial production is running behind battery-electric vehicles.

'Why isn't Cemex sticking with diesel mixers? There are three compelling reasons: cost; health; and climate change.'

”Apart from the challenge of producing green hydrogen, moving it around and storing it requires special care, pushing up costs. Plus, as green hydrogen comes onstream, it will likely get gobbled up by industrial users that don’t have any zero-emission alternatives. So the current balance of opinion favors hydrogen as a solution more for niche cases, such as mining operations or "drayage" trucking from ports to distribution hubs, where refueling depots can be centralized.

The price tag for this charging and refueling infrastructure — $32 billion to $42 billion up to 2030 in Europe alone, according to the World Economic Forum’s "Road Freight Zero" report — requires serious public sector commitment. In a bid to accelerate this roll-out, three truck makers — Daimler, Traton and Volvo — have announced plans to co-invest $529 million to install and operate at least 1,700 charging points across Europe for heavy, long-distance electric trucking within five years of getting the necessary approvals.

U-turn on fossil fuels

Given the shocking data on trucking’s impact on human and planetary health, there’s only one direction in which trucking can responsibly head.

Carbon dioxide emissions from trucks have climbed inexorably this century, rising by 64.5 percent since 2001, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Emissions from heavy-duty trucks are very nearly double those from medium-sized trucks. But to have a chance of hitting IEA’s net-zero scenario, they all need to head the other way — falling by at least 16 percent by 2030.

It’s a bit like doing a U-turn up a one-way street in a 16-wheeler. But if anyone can do it, a trucker can.

Jonathan Walter and Andrew Alcorta contributed to this article.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

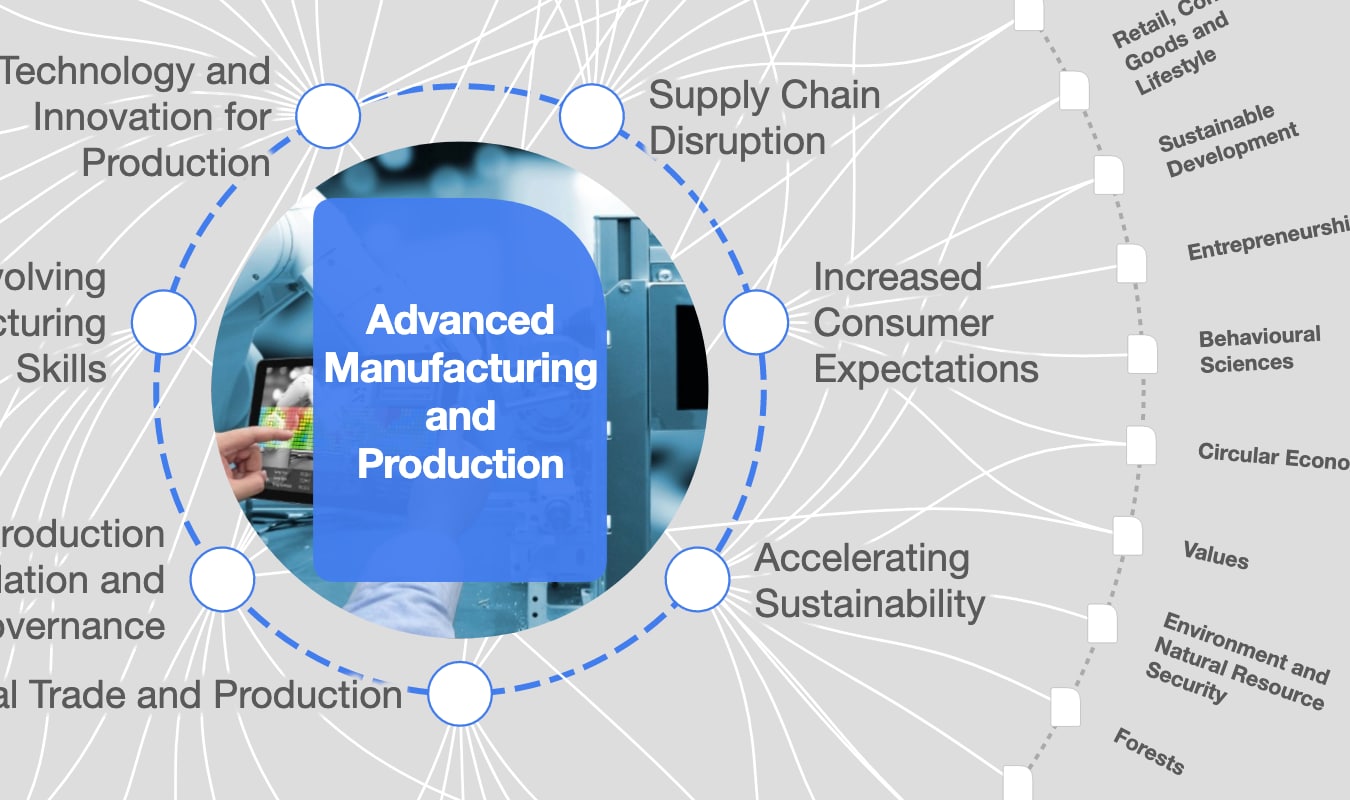

Future of Manufacturing

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Manufacturing and Value ChainsSee all

Caroline Narich, Maria De Miguel, Jessika E. Trancik and Christine Gschwendtner

November 12, 2025