Why improving women’s health must become a social and national priority

Women’s health is still not cemented in national policy decisions. Image: Unsplash/National Cancer Institute

Listen to the article

- Research by Roche Diagnostics sheds light on why overcoming societal and systemic barriers for women’s health is important in Asia-Pacific countries.

- The lack of effective screening programmes can explain why developing countries have higher cervical cancer rates.

- Including women in healthcare decision-making while localizing strategies can help redress access to health inequities and improve women’s health.

Australia is on track to being one of the first countries to eliminate cervical cancer. Its pioneering self-collection programme for cervical cancer tests to all women and people with a cervix is one of many ways it reaffirms its commitment to eliminate the disease by 2035.

Establishing its National Cervical Screening Programme in 1991, the 25 million-strong nation has been a frontrunner in global eradication efforts. Now, ongoing vaccination and screening, strong political will and evidence-backed policies could help Australia make cervical cancer a thing of the past. And its achievement could provide a blueprint for others to eliminate one of the only preventable and curable cancers, if detected early, in our lifetime.

However, women-specific diseases and health, in general, have not been cemented in national policy discussions in Asia Pacific countries and leave women at the sharp end of access to health inequity.

Prioritizing preventable women’s health concerns

The experience during the COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point. The global emergency resulted in decreasing HPV vaccination rates, screening and treatment, leading to more women presenting with late-stage cervical cancer, which requires more invasive and less effective treatment.

Only a handful of countries have a comprehensive cervical cancer elimination strategy. In developed countries, incidence rates of cervical cancer are generally low, around 3.6%. The disproportionate burden of cervical cancer in developing countries and medically underserved populations is mainly due to a lack of effective screening programmes.

Beyond nationally driven efforts, there may be access to clearly visible health challenges, societal expectations and barriers that create “invisible” barriers preventing women from getting the care they deserve.

For instance, an Asia Pacific-wide survey by Roche Diagnostics of 3,320 women across eight countries found that 21% of women felt strongly that they are more likely to have delayed or avoided medical treatment one or several times due to a family obligation.

The same research found that knowledge gaps weren’t responsible for women not opting for screenings. High-income respondents from emerging markets like China, India and Indonesia said they felt very or somewhat knowledgeable about cervical cancer (93%, 91% and 78%, respectively). But there remains a barrier to acting, as publicly cited data shows cervical cancer burdens in these countries are not declining and mortality rates of cervical cancer burden in China and India remain the highest in Asia.

As productive and contributing members of society, women-specific health concerns should not be ignored in low- or high-income countries.

Many women, including those in higher-income countries like Singapore, delay having children leading to rising susceptibility to pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, which is responsible for around 15% of all premature births and 42% of maternal deaths worldwide. Early detection and effective care can vastly reduce the number of preeclampsia-related fatalities and complications but the condition is difficult to diagnose as its symptoms – high blood pressure and swollen feet, ankles and hands – can be mistaken for the normal effects of pregnancy.

Better health equity can raise awareness and knowledge levels and inspire tangible action in designing policies that give women access to tests and treatments that will afford them longer and healthier lives.

Shifting the narrative from equality to equity

Men and women each face diverse health concerns across their lifespan but when barriers impact one gender above the other, the question arises as to why healthcare inequities still exist.

More importantly, women’s health should not be limited to gynaecological and reproductive health. Women are much more likely to have atypical heart attack symptoms and be affected by autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis or lupus.

Systemic under-investment preventing access to screening for women-specific diseases and inconsistent implementation of national guidelines for women’s health has continued to widen health equity gaps. In three-quarters of cases, diseases that affect women primarily are underfunded compared to conditions that primarily affect men.

Diagnostics is a crucial pillar for healthcare systems, as early and accurate diagnoses significantly impact effective treatment and health outcomes. However, women can face barriers in accessing diagnostic tests, and as data from Roche’s Global Value of Diagnostics survey across the Asia Pacific suggests, these barriers to diagnostics can negatively impact women more than men.

However, there needs to be more than a stop-gap approach to offering tests. According to a report by Foundation for Innovative Diagnostics (FIND) and Women in Global Health, more women in leadership positions – at community, health system and political levels – can drive access to testing.

Much still needs to be done to encourage better access to diagnostics, particularly for women. It begins with policy decisions, ensuring health systems provide for women and that there are accessible tests specific for prevalent conditions unique to them.

Instead of a one-size-fits-all solution, a localized strategy will effectively support developing health systems where a shortage of appropriate hospital or laboratory infrastructure and specialist resources can create additional challenges. Healthcare systems must embrace these differences when communicating, policy shaping and funding research, allowing women to access the information, diagnosis, treatment and care they need when they need it.

At the family level, women control 80% of healthcare decisions in the home. . . despite often experiencing the widest health access gap.

”Every change matters

At the heart of such societal and systemic shift lies a desire for everyone to want to create change in mindset, behaviours, policies and funding. However, it will take more than empowering women to be more central in their own healthcare decisions to drive change.

As nations rethink how to efficiently apply resources to tackle growing healthcare challenges – the increasing burden of diseases, rising healthcare costs, and inequitable access – the time is ripe to enhance equitable health systems to create greater value for women.

At the family level, women control 80% of healthcare decisions in the home. As the primary caretakers of the family, they make appointments and healthcare purchasing decisions on behalf of partners, children and parents, despite often experiencing the widest health access gap.

And while the role of women in society has evolved, there is still societal pressure to meet certain expectations that can influence major life decisions, from pursuing higher education, giving up their careers and becoming caregivers to getting married at the “right” age. These compounding factors should be considered when explaining varying health-seeking behaviours and the underrepresentation of women in healthcare.

And that is why it is incumbent upon all of us to keep having conversations and collaborating with like-minded stakeholders to raise awareness and shape policies to yield long-term and meaningful solutions that improve women's health outcomes in Asia Pacific and everywhere.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

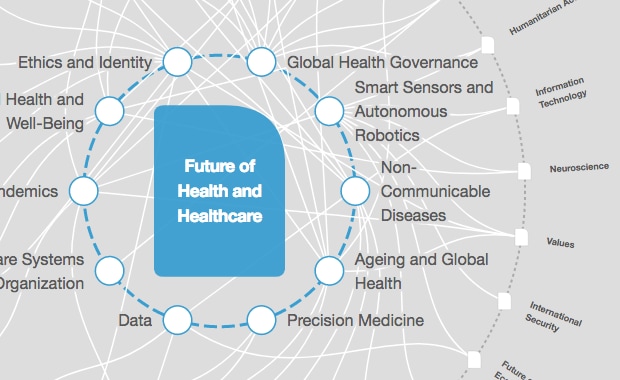

Health and Healthcare

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Mansoor Al Mansoori and Noura Al Ghaithi

November 14, 2025